WORDS: Gareth E Rees

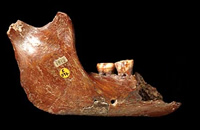

Charles Dawson was the Uckfield solicitor who discovered Piltdown Man in East Sussex in 1912 – a broken skull buried in million-year-old gravel deposits alongside a carved elephant femur and other fragments.

Proclaimed at the time to be the ‘missing link’ this turned out to be a forgery, perpetuated by Dawson and coming hot on the heels of a lifetime spent manipulating archaeological and antiquarian finds.

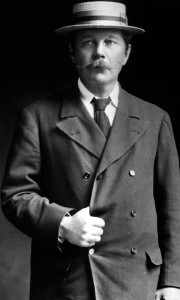

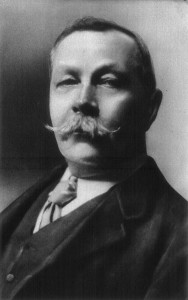

The same year, Dawson’s correspondent, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, released his novel The Lost World.

This is an unofficial version of what really happened.

———————————————————————————————————–

In 1911, the night after he enjoyed lunch at the home of Arthur Conan Doyle, Charles Dawson had a dream.

A humanoid creature with a bulbous cranium and jutting jaw emerged from a fog and moved towards him, stretching out long simian arms.

Dawson was awed. There was so much he wanted to ask.

…How old are you? How did you live? What did you eat? How did you die? How can I show you to the world?

But before could speak, he was woken by the angry ringing of an alarm clock.

Over breakfast, he explained the dream to his wife, Helene.

“It is a sign that I am should pursue my instincts regarding Piltdown,” he said, toast crumbs falling from his moustache. “For that was as close to an ape man as I’ve ever envisioned, albeit in my mind’s eye. I am on the correct path, I am sure of it.”

“I expect that Mr Conan Doyle has filled your head with stories,” said Helene, tapping her boiled egg with a spoon.

“Ha ha! On the contrary, dear, the situation may well be the reverse. Much of what Arthur knows about palaeontology has come from our correspondence. This book he is writing, the one about ape men and dinosaurs, I dare say it’s a product of his fossil hunting, an endeavour in which I have aided him greatly.”

“Perhaps you should write your own book and pip him to the post.”

“I have no need to write anything as flimsy as a book,” smiled Dawson, “the Weald is my novel, and I write a new chapter with every dig and discovery.”

With that he stood up, bowed comically to his wife, and left for work on his bicycle, whistling Caruso’s La Donna E Mobile.

Arriving in Uckfield, he entered his office, carefully shutting the door behind him.

Spread out across this mahogany desk – as well as numerous small tables and makeshift platforms – were dozens of vessels filled with brown liquid. Fragments of human bone bobbed inside, slowly staining in the solution. A shelf was stacked with trays of teeth, mandibles, flints, vertebrae, chunks pelvis, ribs and all manner of prehistoric jetsam.

A fossilised elephant’s femur was propped against the wall. Beside it, an open steel chest was piled with modern tools: files, hacksaws, chisels and hammers.

Dawson hurriedly opened the window to release the chemical stink which had accrued overnight. From a locked drawer he removed a two hundred year old jaw bone, hauled from a dig in Hastings’ East Hill over a decade ago, not that anyone would remember, so sloppily had it been documented.

It was an Orang-utan’s jaw, but not for much longer.

Dawson paused, as if to pay due respect to the moment. For he knew famous this jaw would become, once discovered. The venerable Mr Conan Doyle was not the only one capable of creating ape men. Ink pens and novels were one way of finding fame and fortune, but Dawson could write history with bones.

Clipping on his pince-nez, he peered hard at the jaw.

“Now, to work.”

Slowly, carefully, he began to file down the teeth.

*****

“Charles?”

A voice outside Dawson’s door. In panic, he looked his clock. Almost 6:30pm. What on earth would somebody want at this time?

“I say, Charles, are you there?”

The door handle rattled. There was no time to conceal the chemical solution. The solicitor stood to his feet, quickly, intending to put the elephant femur on a high shelf, but the door swung open before he could move from the spot.

In the doorway stood Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, hat in his hands, cane pointed directly at him like a shotgun.

“Sir Arthur!” Dawson bellowed, overly loudly, forcing a grin.

Doyle’s moustache bristled as he opened his mouth to say something, but then his eyes fixed on the giant leg bone in Dawson’s hands.

“Ah, this?” With a guffaw, Dawson lurched forward, mimicking a defensive stroke, “In idle moments I like to imagine playing a little cricket.”

“I see,” said Doyle.

“To what do I owe the pleasure?” Gripped by nerves, Dawson forgot for a moment that the bone wasn’t really a cricket bat. He tried to lean against it casually but the femur was too short, so he ended up bent sideways like a child doing the little teapot song. Rather than correct himself, he remained leaned, as it were his natural standing position.

“And the smell?” asked Doyle.

“The smell?”

“The smell,” replied Doyle, pointing his cane at the vessels of liquid. “Bi-chromate of potash, I presume?”

Dawson blanched. How could he know?

At the sight of Dawson squirming, Doyle smiled. “Look here, I apologise for turning up announced. I was passing by and it occurred to me suddenly that you might still be at your work. It’s rather urgent and regarding this piece of cranium in Piltdown. You say it might be very old.”

“As old as the deposits themselves,” said Dawson, attempting to prop the elephant femur under the desk behind him, noticing Doyle’s gaze scanning the trays of bone fragments, one of which contained the orang-utan jawbone. “I have been digging the pits with my friend Teilhard and we have found a second fragment of that same skull. With a bit of luck, there is more.”

“Human?”

“Perhaps older.”

“Ape?”

“Possibly somewhere in between.”

Doyle tapped his fingers on the door frame, breathing deeply. For a fleeting second he wondered whether he’d made a mistake about Dawson’s forgeries. But like his famous detective, Doyle was convinced of his deductions.

Doyle tapped his fingers on the door frame, breathing deeply. For a fleeting second he wondered whether he’d made a mistake about Dawson’s forgeries. But like his famous detective, Doyle was convinced of his deductions.

Besides he had to think what a discovery of a real ape man would do for sales of The Lost World.

“I have had some further thoughts about my forthcoming novel.” Doyle stepped fully into the office and closed the door. “I believe you might be able to help me with a little…. publicity…. an offer I am sure to which you will be amenable, bearing in mind my suspicions about your clandestine activities. Suspicions which I have no doubt, are correct.”

He jabbed his cane at the various tools, bones and jars of liquid around the room, “Exhibit A, exhibit B, Exhibit C, Exhibit D, Exhibit E. And so on and so forth. All the evidence required. Case closed. Elementary, my dear Dawson.”

Mortified, Dawson gripped the elephant femur tightly. For a moment he considered slamming it with force on the author’s cranium.

He had enough abrasive chemicals in the office to turn the author into a fossil and bury him in Piltdown. He could later ‘discover’ Conan Doyle with a monkey’s jaw wedged onto his face in an eternal gibbering grin.

“Oh, and there’s no need to put that leg bone away, Dawson,” said the author. “It may come in useful.”

****

Gareth E. Rees is author of Marshland: Dreams & Nightmares on the Edge of London. His work appears in Mount London: Ascents In the Vertical City, Acquired for Development By: A Hackney Anthology, and the album A Dream Life of Hackney Marshes. His essay ‘Wooden Stones’ is included in the forthcoming Walking Inside Out: Contemporary British Psychogeography.