WORDS: Joe Barton

PICTURES: Jack Gardner

LOCATION: Newcastle upon Tyne’s Quayside

Content warning: this article contains references to suicide.

There is a ghost story in Newcastle about a haunted Quayside alleyway. It goes something like this:

A keelman staggers out of a warm tavern and into the bitter night. The wind on the Quay is down, but the cold bites just as hard without it. He buttons his jacket with his left hand and, with his right, rummages through his pockets for a sixpence to pay for a bed at the Lifeboat Inn. Finding a mere ha’penny, he decides to try his luck with the landlady all the same. Steeling himself for an argument, he pulls his bonnet over his brow and makes haste for his lodgings.

The keelman treks along the Tyne, flanked on his right by a row of ships resting at anchor. He hears a rustling sound and stops to study their masts but, to his confusion, sees nothing but rolled sails. Only when he resumes his homeward march does he see her. On the other side of the road, a woman is moving in the same direction as him, matching his brisk pace. The rustling, he now realises, is the sound of her long white dress dragging along the pavement. He glances at her face but, before he can make it out, she darts down an alleyway. As she disappears from view, something falls in her wake with a glimmer and a clink. He crosses the road, halts at the opening of the alley and stoops down to the ground. He plucks the coin from the cobbles and studies it under the moonlight: a newly minted gold sovereign, enough to keep a roof over his head until Christmas. He clutches it tightly and steps into the darkness.

At first, he sees nothing. As his eyes adjust slowly to the dark, the woman remerges a few yards ahead, and he notices for the first time that she is wearing a wedding veil. She raises a hand and silently beckons him closer. As he approaches, she lifts the veil. There is nothing underneath it.

*

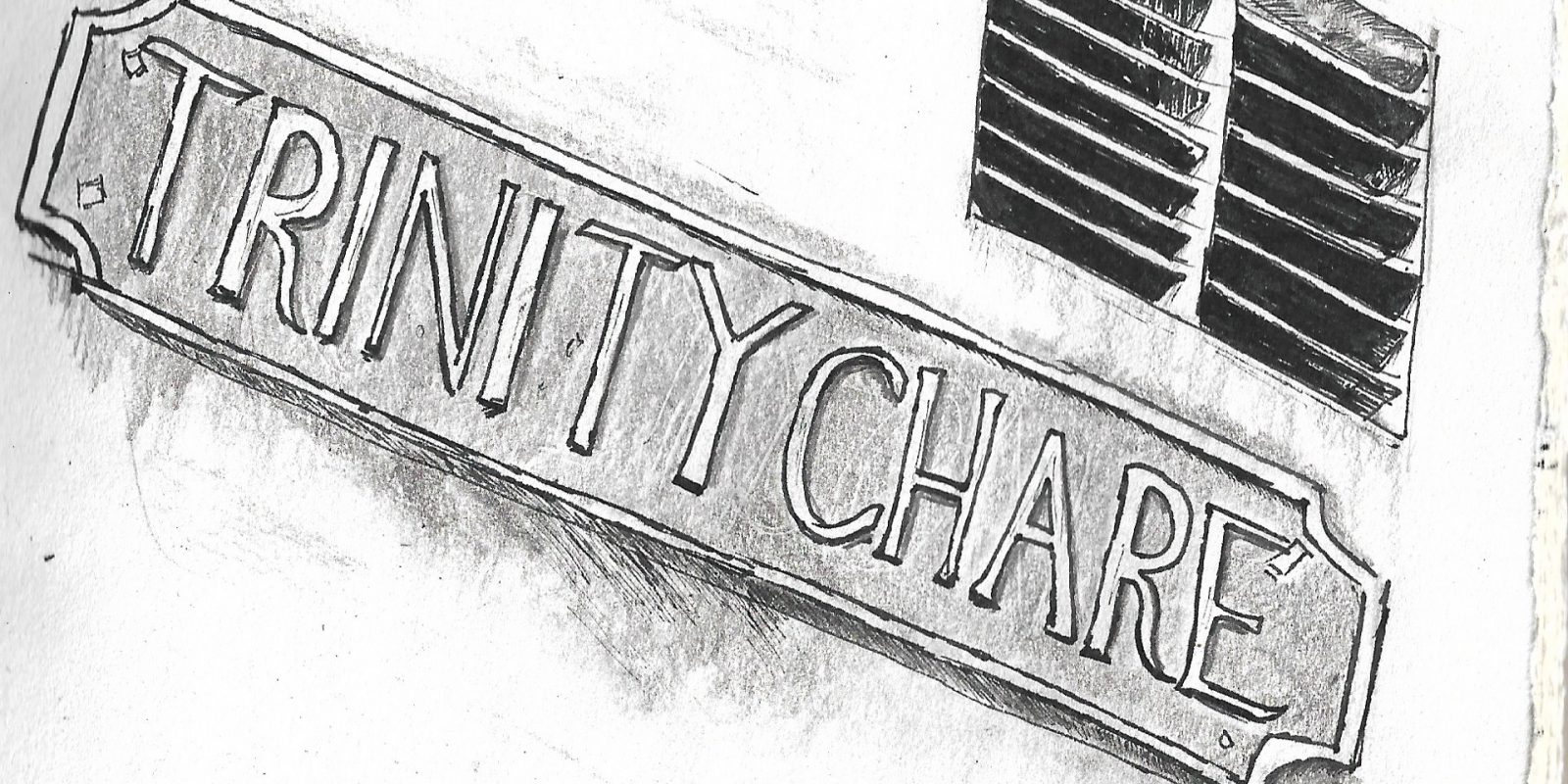

Four compendiums of Geordie folklore published in the last 30 years include a version of this story. All four of them identify the haunted alley as Trinity Chare: one of the medieval side streets that branch out from the main promenade of the Quayside. Anyone visiting this location today in search of a supernatural encounter, however, risks disappointment. No longer a shadowy passageway, Trinity Chare is now an artfully lit thoroughfare between a barristers’ chambers and the offices of a software company who specialise in ‘content-production solutions’. Those of us keen to get closer to the ghost are better off starting with the story itself rather than its setting.

Every variation of the tale features the central figure of a veiled woman dressed in rustling silks who, when approached, lifts her shroud to reveal that she has no face. Three versions also claim that this faceless apparition is the ghost of a local widow who died by suicide and was interred at a nearby crossroads with a stake driven through her heart. Unlike the keelman, then, we find ourselves in pursuit of, not one, but two mysterious characters: a silken ghost and a local widow. The prospect of explaining their origins glimmers like a gold coin in the moonlight. To find out more, we have no choice but to follow these two figures into the dark.

The trail of the silken ghost leads us to a small village 12 miles northwest of Newcastle. A late Victorian compendium of northern folklore reports that, in the early nineteenth century, the villagers of Black Heddon in Northumberland were ‘greatly disturbed’ by a robed female figure known as ‘Silky’, who:

…was remarkable for the suddenness with which she would appear to benighted travellers, breaking forth upon them, in dazzling splendour, in the darkest and most lonely parts of the road. If he were on horseback, she would seat herself behind him, “rustling in her silks”…

The villagers believed that Silky ‘was the troubled phantom of some person who had died miserable because she owned treasure and was overtaken by her mortal agony before she had disclosed its hiding-place.’ In the neighbouring village of Belsay, Silky was known to haunt an old tree that stood beside a waterfall and a lake. To this day, the tree is known as ‘Silky’s Chair’.

Silky of Black Heddon shares much with the ghost of Trinity Chare: her origins in agony and despair, her rustling dress, her waterside hauntings, her appearances to benighted passers-by. Given these similarities, as well as Newcastle’s proximity to Black Heddon, it is easy to read this modern ghost story as a translation of rural folklore into an industrial setting. It could have come about after a villager migrated to Newcastle in search of employment, taking the tale of Silky with them. Alternatively, a Tyneside labourer might have taken up seasonal work on a Northumberland farm and brought a ghost story back with their pay packet. Somewhere along the line, a crag became a Quay, and a country lane became an alleyway.

The trail of the silken ghost tales us further, out to the western edges of Northumberland and beyond. Blenkinsopp Castle, near the border with Cumbria, is said to be haunted by a woman ‘clothed in white from head to foot’, who cannot rest while a chest of gold remains in the castle’s vault. Further afield in Wales, there are several White Lady ghost stories. Once again, the figure is depicted as the spirit of a woman in possession of hidden treasure, who died as a result of murder or suicide before she had the chance to tell others of its whereabouts. The Lady in White of Llangwm in Conwy, for example, is said to have died by ‘by throwing herself into a lake near where she lived’, while another tale from Mid Wales features a woman ‘attired in a lustring silk dress, and her face covered by a silken veil’.

Nor does this trail end in the nineteenth century. The folklorist Jane C Beck claims that the White Lady is a modern iteration of the lake-dwelling water fairy Morgan Le Fay, which is, in turn, a corruption of Modron, the supernatural mother figure who appears in Middle Welsh prose tale Culhwch and Olwen. Beck goes even further to propose that Modron is, in turn, descended from the pre-Christian Mother Goddesses of Celtic Briton. These ‘Matronae’, as the Latin altar inscriptions dating from the period of Roman occupation call them, were embodiments of fertility and natural abundance, which, for Beck, is the ultimate origin of the longstanding trope of unclaimed treasure in the White Lady lore.

To follow the White Lady from her ancient origins back to the Newcastle Quayside, then, is to witness her two millennia-long demotion ‘from a mother goddess to a kind of fairy and finally to a ghost’. Along the way, we see a deity once lauded for her life-giving gifts becomes a haunting spectre, feared for sharing not her treasure, but her trauma.

Back at Trinity Chare, the second figure –that of the local widow– also begins to emerge from the shadows. All three versions of the tale that mention the widow identify her as one Martha Wilson – a woman whose death does in fact appear in the historical records. A notice in the Saturday 26th April 1817 edition of the Durham County Advertiser announces that:

‘On Wednesday, an inquest was held on the body of Martha Wilson, of the Trinity House, Newcastle, who hung herself on Sunday evening. Verdict, Felo de se. Her body was on Thursday evening buried in the public-road leading from the New Bridge to the Red Barns, a little beyond the turnpike gate.’

This account is expanded upon some 70 years later in the Monthly Chronicle of North-country Lore and Legend, which explains that Wilson was:

‘a seaman’s widow, subject, as was said at the time, to frequent fits of melancholy. There were seasons in which she had threatened to destroy herself; and to this sad end she came on Sunday, the 13th April, 1817. She had that morning been to a huckster’s shop, where she purchased a little tobacco; after which she was no more seen alive. She was missing until the following Tuesday, when she was found dead in her room at the Trinity House [….] her door-key was lying on the floor; her prayer-book lay open on the bed. There was a coroner’s inquest on Wednesday; witnesses were examined and the jury, on what grounds is not recorded, returned a verdict of Felo de se.

The charge of felo de se, or ‘felon of themself’, in cases of death by suicide stemmed from the belief that, as English subjects were the personal property of the monarch, a completed suicide thus constituted an act of theft against the Crown. Moreover, as the church held that suicide was an unrepentable sin that nullified one’s relationship to God, a ruling of felo de se thus sanctioned the desecration of the deceased’s corpse through a profane burial at a crossroads. After excommunicating the deceased, and thus denying their soul a direct ascent to Heaven, their body was buried face down to prevent it from facing God on Judgement Day. Driving a stake through the heart of the deceased’s corpse, furthermore, was said to pin their soul to the crossroads, thus dooming it to confusion and consternation should it rise from the ground after dark. Having spent the night unable to decide which way to go, the soul of the departed was expected to return to the earth with the coming of the dawn light.

Rulings of felo de se were extremely rare by the time of the inquest into Martha Wilson’s death, and the account from the Monthly Chronicle notes that her profane burial was the last recorded instance of the practice in Newcastle before it was abolished in 1823. The grounds for the jury’s ruling in Wilson’s case are, as the Chronicle notes, ‘not recorded’. It could be that the views of Newcastle’s establishment were out of step with the softening attitudes of social elites elsewhere in the country. Alternatively, the inquest might have been influenced by the concerns of the small dissenting communities that met in rooms in the streets around Trinity House; in contrast to the Church of England, many non-conformist churches continued to profess the belief that the Devil played an active role in driving a despairing person to take their own life and, moreover, that he lingered at the site of death thereafter. For adherents to this view, the corpse of a person who had died by suicide was not just spiritually polluted, but a present threat to the souls of the wider community. Perhaps these churches sent representatives to join the ‘large and curious’ crowd that the Chronicle claims witnessed Wilson’s interment on the evening of the 23rd of April, so as to ensure that the ritual of spiritual purging was followed through to completion.

Alongside the parish officials and voyeuristic strangers, the assembly at the crossroads that night may have included some of those that had known Martha Wilson from her time at Trinity House. A seafarers’ guild concerned with the welfare of local mariners and their families, Trinity House owned a number of alms houses on Trinity Chare for the dependents of deceased sailors. The guild’s records show that, in the years leading up to 1817, a number of widows petitioned for accommodation in its alms houses, including Mary Gray, Sarah Fenwick, Elizabeth Johnson, Elizabeth Taylor, Mary Stephenson, Ann Wardle, Ann Maxwell, Elizabeth Coulson, Margaret Brown and Mary Ridley. It is likely that some of these women would have known –or at least, would have known of– Martha Wilson. Indeed, the minutes from the meeting of the Board of Trinity House on 5th of May 1817 note that ‘Mrs Sarah Davison, widow of the late Robert Davison, petitioned for the room in the high yard vacant by the death of Martha Wilson’. Her successful request reflects a wider pattern in the guild’s records, in which men petition the Board to become brethren and elders and women petition them not to be made destitute by their widowhood.

While we know who took Martha Wilson’s room, we do not know who took her name and gave it to a ghost. Perhaps an acquaintance of Wilson’s, familiar with the story of Silky, saw a parallel between their late friend and the ‘troubled phantom’ of a woman ‘overtaken by her mortal agony’, and decided to grant Wilson a return to the neighbourhood from which she had been exiled. Maybe, as the whispered news of Wilson’s death and burial travelled from chare to chare, gossip gradually gave way to ghost story – one that gave voice to the guilt haunting the community that had condemned her.

These are theories about Wilson’s afterlife. Of the life that came before it, we know little. We do not, for example, know how long Wilson lived as a widow. Nor do we know whether her bereavement brought her grief for a lost sweetheart, relief at the end of a loveless marriage, or fear of an uncertain and insecure future. We do not know when or where she was born, whether she had siblings, or how old she was at the time of her death.

From the entry in the Monthly Chronicle, we do knowthat Wilson ‘purchased a little tobacco’ on the day she died. More strikingly, we know that she was ‘subject […] to frequent fits of melancholy’ and had previously ‘threatened to destroy herself’. Yet again, however, we do not know how her expressions of despair were received: whether they were met with sympathy and support or disdain and disregard. Beyond a few scant details, it seems that every facet of Wilson’s life –her dreams and delusions, her good deeds and bad habits– has vanished without a trace.

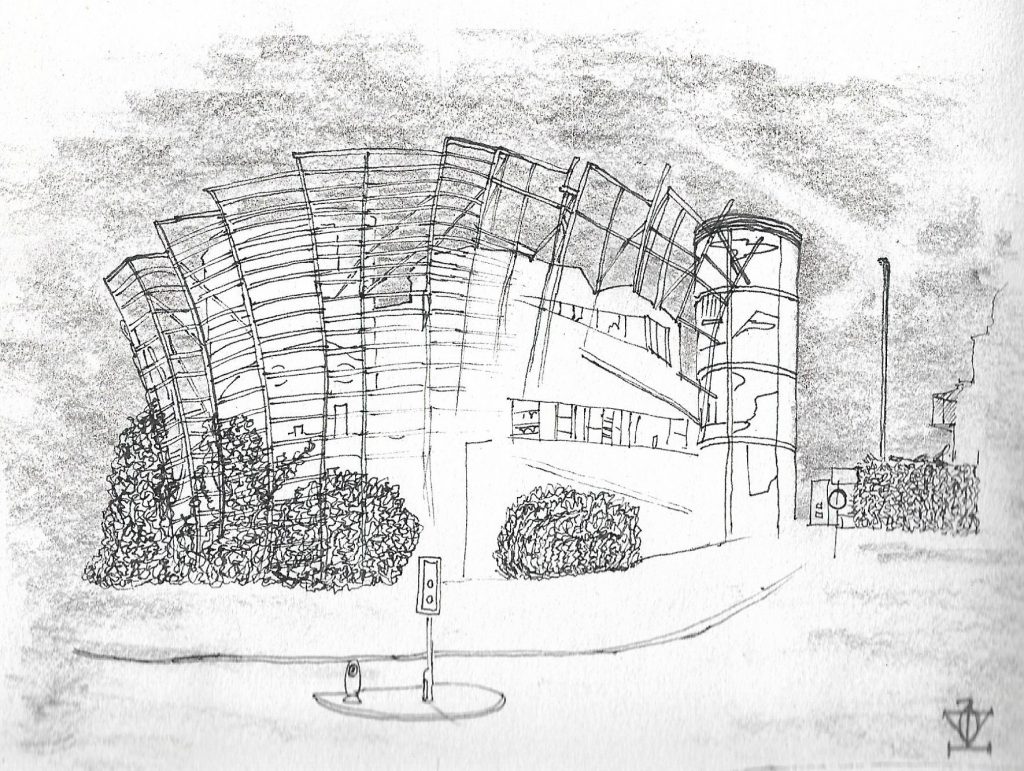

The alms houses in which Wilson and the other widows lived survive to this day in excellent condition. Some are still used by Trinity House –now a registered charity dedicated to ‘the continuance of ancient maritime traditions’– while others are used as offices by the nearby Live Theatre. Wilson’s burial site is still a crossroads, cut through by the A193 and dominated by Northumbria University’s City Campus East.

Whether Wilson’s remains still lie there is another question. The Monthly Chronicle explains that road works carried out on this spot in the 1860s led to the discovery of ‘human remains’ and ‘a piece of wood placed in such a position as to indicate […] a stake through the body’. The attending coroner concluded that the bones constituted evidence of the ‘the last case of local interment of a suicide under the old conditions’. The Chronicle entry speculates that the remains ‘would, in all likelihood’ be put back where they were found but admits that ‘there is no record of this having been done’.

Thousands upon thousands of people have moved through this corner of Newcastle in the two centuries since Martha Wilson’s death, most leaving little or no trace of the time they spent here. For reasons that we will never fully understand, Wilson has been singled out from the multitude, her individual spirit obscured by the circumstances of her death and the shadow of a ghost. Perhaps the sole consolation in all of this is that, through the figure of the White Lady, she has become subsumed into something greater than herself. She has become a bearer of historic treasure, a link in a chain that connects her to an ancient culture and their forgotten goddesses.

This assumes, however, that the origins of the modern White Lady do in fact lie in Celtic worship. As comforting as it may be to trace the apparent continuities between the Regency period and the Iron Age, the fact remains that navigating time is a risky endeavour. The altars dedicated to the Matronae may well still rest on these shores, but the lifeworld that gave them meaning lies on the far side of a vast ocean, and the bridges we build in hope of getting there –each assumption, every conjecture– are rickety at best and rotten at worst. It is our nature to reimagine and misconstrue the past, just as it is the past’s nature to resist and elude us. That is how retrospection becomes introspection, how we see a face where there is no face to be seen.

We can respond to the facelessness of history like the keelman of Quayside lore – by running away from it, chiding ourselves for wandering down the darkened alleyway, cursing that we came back without a gold sovereign. But why should Martha Wilson share anything of her life with those who come after her? Her posthumous degradations cannot be undone, but there is no reason why the exploitation should continue into the afterlife. Wilson’s spirit –her interior world, her private relationships– were never passed on before she passed on. Like Silky of Black Heddon, the White Lady of the Quayside did not give away her treasure before she was overtaken by mortal agony. Perhaps that is a cause for celebration rather than mourning. After all, the details of Wilson’s life were never anyone’s business but her own. They died with her and are all the more precious for it. Her treasure was her spirit, and she took it with her.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Joe Barton and Jack Gardner live and work in Newcastle upon Tyne. In their spare time, they trek around Tyneside in search of the unexpected and overlooked.

Website – www.ontyneside.com

Twitter – @OnTyneside