LOCATION: Fairlight, East Sussex

WORDS: Gareth E. Rees

The village of Fairlight is built on a cliff that’s eroding at the rate of twenty-five metres a year. Its inhabitants rely on the protection of a sea barrier made from Norwegian granite boulders.

The foreshore beneath the cliffs is a fossil hunter’s paradise. Its sandstone and clay deposits were left here in the early Cretaceous, 140 million years ago, by rivers flowing to a lagoon, bringing the fragments of plants animal corpses, which settled to the bottom, creating one of Britain’s most important dinosaur sites outside Devon’s Jurassic Coast.

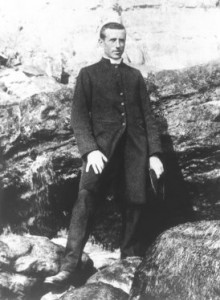

Here was where the young Jesuit priest and palaeontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin once came with his friend Charles Dawson to find fragments of pterosaur, Iguanodon, turtle and crocodile.

Teilhard arrived in Hastings in 1908 to train in Ore’s Jesuit Seminary. An ardent palaeontologist, he spent much of his free time hunting for fossils on the shore.

“This land is new to me, and can teach me quite a bit,” he wrote in a letter to his parents.

As he collected fragments of the past there were moments it seemed as if a universal being was about to take shape in nature before his eyes. For Teilhard these geological explorations were not an act of retrospection, but a process of becoming, of moving towards a truth about God.

While visiting the Old Roar quarry in 1909 he met the local archaeologist Charles Dawson, who was managing the extraction of an Iguanodon’s pelvis, and delighted to gush about it to a new fan. A few weeks later Teilhard invited Dawson to walk with him beneath Fairlight cliffs where he had recently found Iguanodon footprints.

“So high was the tide, and so violent the wind,” he wrote, “the expedition was heroic.”

They were soon firm friends and Teilhard became a regular presence at Dawson’s digs, including those at Piltdown in early 1912, when they found a second fragment of the ape man’s skull near a hippopotamus tooth, corroborating Dawson’s initial discovery.

In the following weeks they dug up animal teeth, worked flints and a piece of mandible. In an excited letter to his parents Teilhard wrote:

“Dawson discovered a new fragment of the famous human skull; he already had three pieces of it, and I myself put a hand on a fragment of an elephant’s molar.”

During his time in East Sussex, Teilhard became convinced of evolution, a problematic idea that had ‘haunted him like a tune’. The elder palaeontologist was fascinated by the way the young priest grappled with evidence of our ape ancestors. But for Teilhard, palaeontology was less about our origins and more about our destination.

The fact we had evolved from apes was not as important as the question ‘why?’

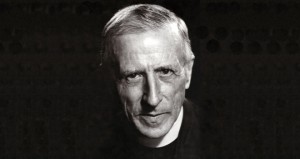

In 1938, eleven years before scientists proved that Charles Dawson’s Piltdown Man discovery was a fraud, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin wrote The Phenomenon of Man, in which he described how evolution was the fundamental driver of the universe.

The birth of the Psychozoic Era

Life on earth had begun with the convergence of carbon compounds into cells, then the organisation of those cells into increasingly complex forms, leading eventually to the creation of human beings with our highly advanced consciousness.

This was a turning point in evolution, beginning what Teilhard termed the psychozoic era.

Like an uncontrollable forest fire, our ideas, cultures and technologies were spreading to form an incandescent psychic layer of thought around the Earth, known as the Noosphere.

Thanks to the discovery of electro-magnetic waves, humans could be simultaneously present everywhere, at all times. Telephones, televisions, Tesla towers. We had the power of remote viewing, of being in one place and seeing in another, of communicating instantaneously across continents, regardless of geography.

We were each a burning bright node connecting with other nodes to become a single phosphorescent hive mind.

He wrote:

“This sudden deluge of cerebralisation, this biological invasion of a new animal type which gradually eliminates or subjects all forms of life that are not human, this irresistible tide of fields and factories, this immense and growing edifice of matter and ideas – all these signs we look at, for days on end – to proclaim that there has been a change in the earth and a change of planetary magnitude.”

Teilhard believed that humankind was in fact evolution become aware of itself. Therefore we were irreplaceable conduits for its future development. Human consciousness would continue to evolve into evermore complex, interconnected arrangements until there would come a point of advancement in which we transcended the material realm and converged with God.

He called this The Omega Point. It was to be our ultimate destination.

*

Picking through Fairlight’s cretaceous graveyard in the footsteps of Teilhard de Chardin, I felt crushed by the vastness of geological time and I craved a pint of ale, which I knew lay inside The Smuggler pub on the shore ahead.

But there was one more epoch for me to traverse first.

On Pett Level the sands at low tide were strewn with the remains of a 6,000 year old forest which was flooded by the last major global ice melt. From a cave in the cliffs, Mesolithic hunters once surveyed the rustling tree tops for signs of prey.

I stepped over ancient branches of oak, birch and hazel, with the queasy realisation that this woodland provided food and shelter for thousands of years to people who thought it their whole world.

But this was no relic of a lost past. It was an intimation of our future.

Teilhard de Chardin wrote that earth’s limited space forced humans to use art, writing and religion to extend their dominion, thereby creating the psychic realm of the Noosphere.

This forest was flooded at the dawn of the Neolithic era when hunter gatherers gave up the endless competition for food to become farmers and builders with a need to organise themselves, lay down their roots and establish founding myths in the landscape.

The rise in sea levels 6,000 years ago that destroyed the forest was a force of terrestrial pressure that helped accelerate this evolution in consciousness, leading to a flight to the nearby East Hill, to topographic modifications of stone and soil for cosmic rituals, to these very thoughts of mine as I walked among the splintered tree trunks with a mobile phone in my hand and the power to transmit their image around the world in a second.

So what will happen after the next great flood?

For the Ice Age is not over yet. Antarctica’s ice is liquefying at an extraordinary rate. Warm waters are seeping beneath its ice shelves, melting them from beneath. Greenland is locked inside 700,000 square miles of frozen water which, when released into the oceans, will swell sea levels by 18 feet, creating monstrous tidal surges that will devastate coastal towns and cities, reshaping estuaries, wetlands and woodlands, sending refugees surging inland to fight over water, food and shelter.

Millions of individuals will certainly die. But if the priest was right, it’s not the end of the world. The coming global warming cataclysm will spark a final, bloody revolution in consciousness. From the carnage might emerge a super-converged collective mind, forced to transcend its physical limitations and escape into the psychic realm.

For more on Charles Dawson, read A Sacred Fake and The Ape Dreams of Charles Dawson.

For more about Hastings, Pett Level, Teilhard De Chardin and Charles Dawson, read my book The Stone Tide.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gareth E. Rees is author of Unofficial Britain (Elliott & Thompson, 2020) Car Park Life (Influx Press 2019), The Stone Tide (Influx Press, 2018) and Marshland (Influx Press, 2013).