LOCATION: London

LOCATION: London

WORDS: Alex Cochrane

Victorian London was a charnel house of the dead; a city oozing horror and nowhere more so than a small chapel where they danced on the dead.

By 1842 London was the modern mega city of the world. For some of her 2.5 million inhabitants it was an exciting, fashionable and thriving metropolis. For many it was a city of squalor, decay, epidemics and early death and the disposal of the dead was becoming an increasing problem for the living.

London’s population had exploded but the authorities did not plan for the increasing numbers of the dead. Burial grounds and churchyards were filled beyond capacity with coffins stacked on top of each other in deep shafts. Open graves sat just feet from the living world. The dead lay amongst the living while they tried to raise funds for a funeral. Corpses of debtors could be seized by bailiffs. Drunk gravediggers cut coffins and dumped putrefying bodies in pits and landfill to make more space, or ground up bones to be sold as bone-meal for the Kent market gardens. Clergyman and sextons turned a blind eye, their income dependent on burial fees. Body pits were hidden from mourners who could be standing around a coffin with the wrong body as rats dragged bones through the gloom.

Gravediggers suffered health problems from the leaking miasma, and could even die suffocating from the the release of “cadaverous vapours”1 when breaking into bloated coffins. There were incidents of coffins exploding from corpse gas build-up, and starting underground fires that burned for days underneath London churches.

Just off the Strand the ‘Green Ground’ was devoid of trees because the soil was ‘saturated, absolutely saturated with human putrescence.’2 The walls dripped with reeking fluids and the smell was so bad no neighbours could open their windows. For the poor the grim internment of the dead was in many ways merely an extension of their living conditions.

Few places though could equal the horror of Enon Chapel.

Enon Chapel was opened in April 1822 by a corrupt and greedy Baptist minister, Mr W. Howse. The chapel was built over an open sewer in Clements Lane, close to the Strand. The local residents suffered from appalling smells, vast numbers of rats and an atmosphere so putrid that it rotted exposed meat within hours. The local children noted the insects and flies crawling out of the coffins and vaults and nicknamed them ‘body bugs’. It wasn’t much better for the congregation either, who regularly passed out during services.

The cause lay under the flimsy floorboards but it was only discovered in 1839 when the authorities wanted to replace the open sewer. They made a grim discovery. The chapel was a charnel house that defied sanity. Offering far cheaper services than his rivals, Howse had over the years buried an estimated 12,000 bodies in a space fifty-nine feet by twelve. Vast numbers of decomposing bodies were separated from the living by a few inches of earth and some flimsy floorboards. To pack-in more bodies Howse emptied the coffins and burnt them for firewood. He dowsed bodies in quicklime for quicker decomposition, dumped human remains to fester in the sewer and loaded carts to discard into the Thames and landfill at Waterloo Bridge. He had got away with it by exploiting the fear many had of body snatchers removing their loved ones. They believed that the churchyards were more secure than more open burial grounds and cemeteries.

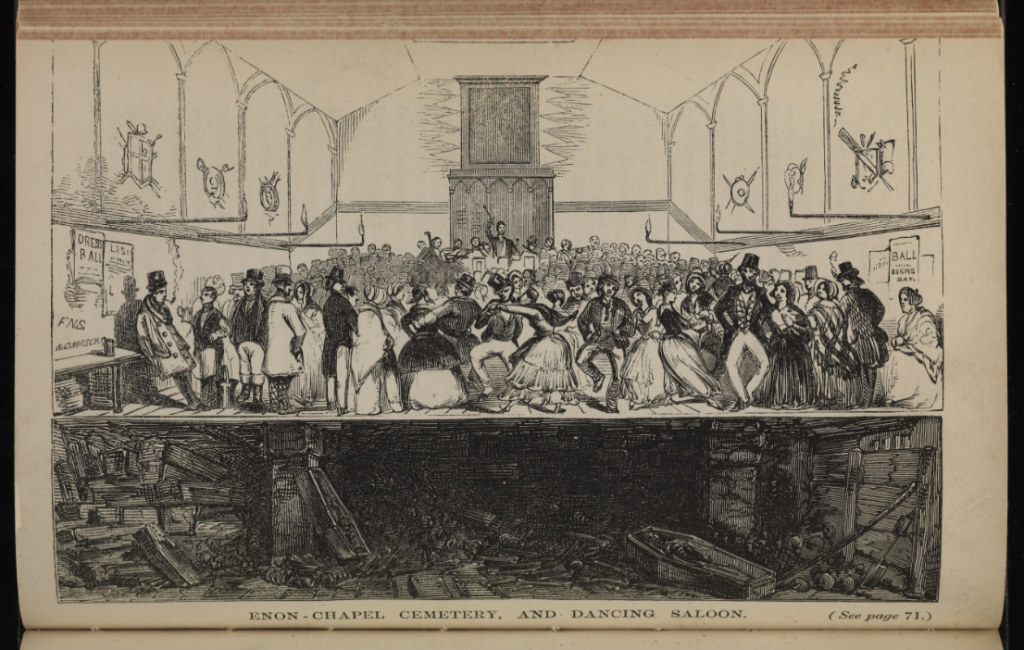

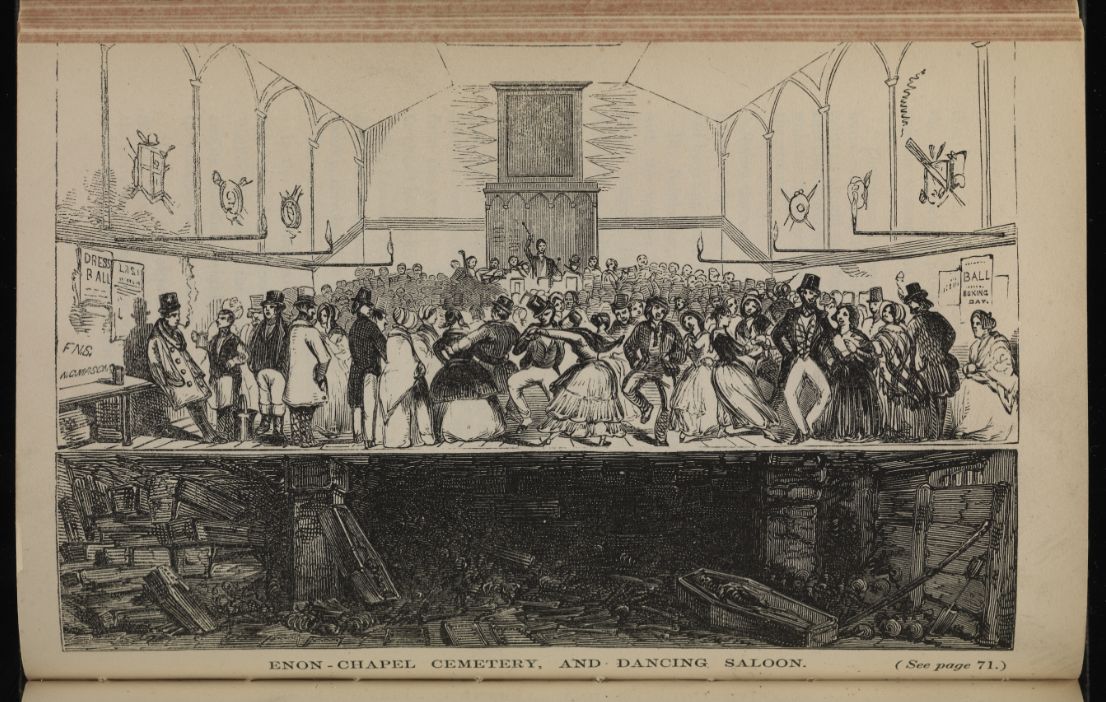

The authorities closed the chapel and vaulted over the sewer but, unbelievably, did not remove the bodies. The chapel was renamed Clare Market Chapel and let to a teetotaller sect who exploited the macabre history of the chapel for tea dances, fancy dress balls and gambling. ‘Dances on the dead’ went the advert, which also insisted that lady and gentlemen must wear shoes and stockings for admittance.

“Quadrilles, waltzes, country-dances, gallopades, reels are danced over the masses of mortality in the cellar beneath”3 described the Poor Man’s Guardian in 1847.

Eventually campaigners, led by the sanitary reformer George Walker, took over the chapel in 1847 and starting exhuming the dead, moving the remains to the new Norwood Cemetery. This process became another spectacle for Londoners who gathered to stare at the “pyramid of bones…exposed to view”4.

Enon Chapel was not the only place where such practices occurred, but it was the most notorious and provided useful propaganda horror for reform campaigners such as Walker. The government finally responded to the pressure, passing the Burial Act in 1852 that closed burial grounds in the city. It paved the way to the development of the great Victorian cemeteries of Highgate, Nunhead and Kensal Green.

Clements Lane has become St. Clements Lane but the chapel is long gone, demolished for development. The present site is now home to the London School of Economics and the Law Courts. London is a clean and efficient city but its foundations and compacted layers are soaked in the effluence and mixed with the bones of its ancient dead.

References

1 Simon, City Medical Reports, 1849

2,4 George. A. Walker, Surgeon Gatherings From Graveyards:

3 The Poor Man’s Guardian, 4th December, 1847

Further reading

Catherine Arnold, Necropolis: London and its dead

Death in the city: the grisly secrets of dealing with Victorian London’s dead

Alex Cochrane is based in Glasgow and blogs about exploration, travel, history, historical erotica and other curiosities at https://adcochrane.wordpress.com. You can also follow Alex on Twitter at @alexdcochrane

[…] Victorian London was a charnel house of the dead; a city oozing horror and nowhere more so than a small chapel where they danced on the dead. Please click for full article published on the Unofficial Britain website […]

Fab piece, and more than a little unnerving

Amazing blog. What a sordid past we have to our credit. Never did much like the vibes of London. They always seemed a bit odious as if the past lived on through the present. Which I believe it does! Eve with thanks.