WORDS: Gareth E. Rees interviews Baz Nichols.

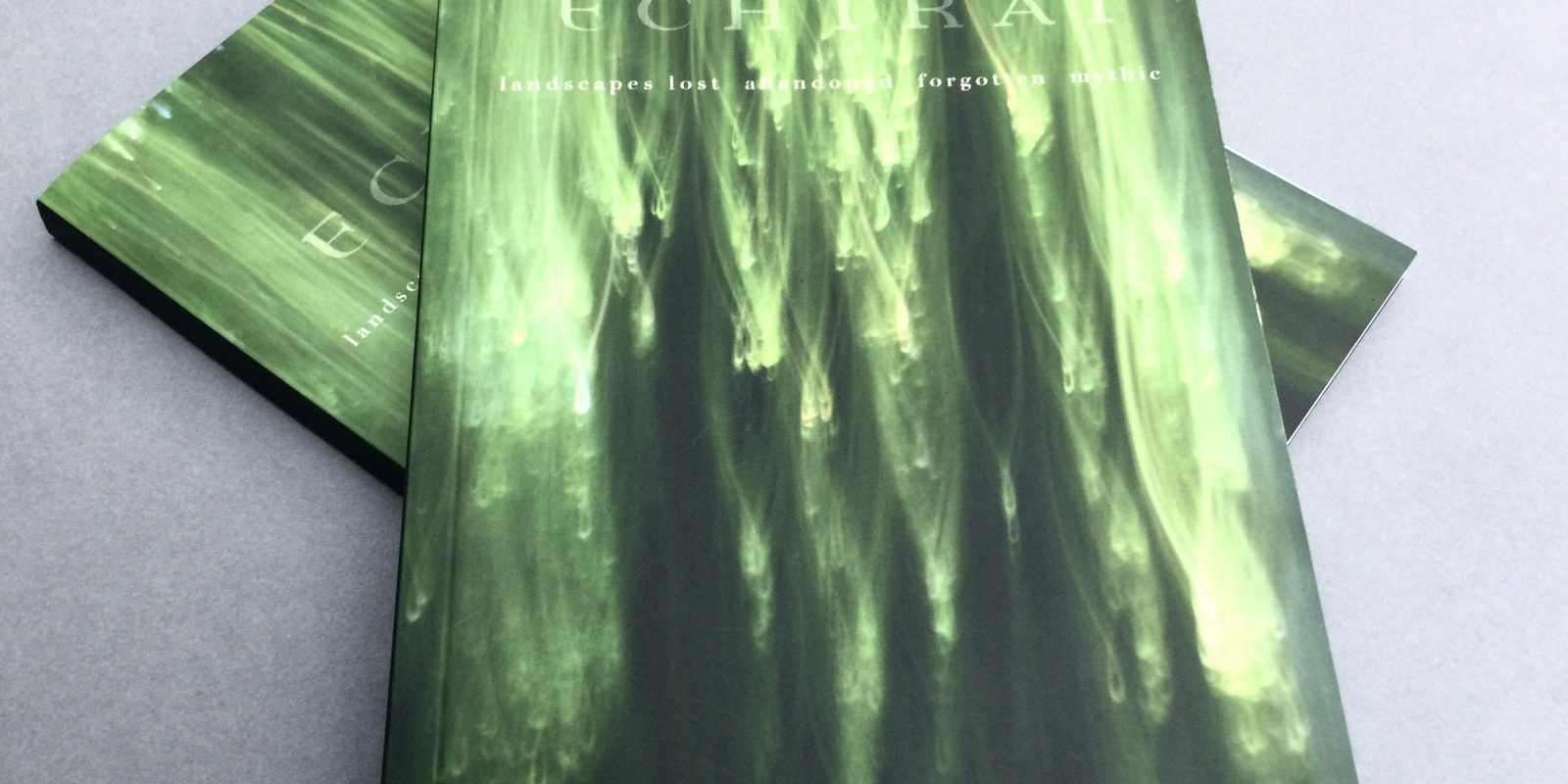

Echtrai is a new journal of writing and art dedicated to lost, abandoned and mythic landscapes. It features work by Dominic Cooper, Louise Kenward, Cal Flyn, Emily Hesse, Jeff Young, Nick Pepper, Laura Harrington, Alex Woodcock, Jon Woolcott, Brighid Black, Dr Lizzie Fisher, Martyn Hudson and Deborah Westmancoat. I got in touch with its founder and editor, Baz Nichols, (who also contributes under the pen name, Bran Graeme Nairne) to find out more.

Gareth E. Rees: Congratulations on the pilot edition of Echtrai. It looks gorgeous. Let’s start with the title – can you briefly explain a bit about the term ‘Echtrai’?

Baz Nichols: I discovered the word Echtrai whilst researching Celtic mythology, a passion of mine. Very briefly, an Echtrai is an odyssey, a mythic journey into the unknown of the Otherworld in Irish mythology. Whilst searching for an appropriate title for the journal, this word seemed to cling, it felt right for the journeys we undertake as writers, and also chimed with the themes that we had set down for the journal itself.

GER: What inspired you to create a journal on the subject of lost landscapes? Does this subject have any links with our contemporary crises?

BN: I have been self publishing small editions of my writing and art seriously since early 2010. I began writing about marginalised landscapes after accidentally discovering an old 12th century church near my (then) home in rural Northamptonshire, and I was inspired to research its history, and began to accumulate a body of writings and incantations based around that.

Going deeper, I was born and brought up in East London in an area that straddled both the city and the rural edgelands of Essex and Hertfordshire. During my formative years, London was still very much in recovery after WW2, it stilled carried with it some of that trauma, and that had a profound affect on everyone living there at the time. My youth was very largely spent exploring these ‘lost zones’, dowsing and absorbing this curious admix of rural wildness and the abandoned factories and wastelands, which obviously had an impact on me psychologically and creatively.

During the Covid pandemic last year, I had time to connect seriously with other like-minded writers and artists that I felt had the quality and literary skill to produce something that had some creative resonance. I think you’re right – the journal very much came about at a time of national crisis, not only in terms of the pandemic, but also a raised awareness of our impact on our climate and ecosystem, and how all of that combined might potentially make us complicit in our own demise as a species.

The British coastline in particular is in rapid transition as sea levels are rising, and the rate of coastal erosion is currently quite alarming. I believe that our knowledge of that makes it all the more urgent that we not only act quickly to avoid a cataclysm, but also start to collectively record and document these places and their stories before they are lost to history.

I really feel deeply that there is a groundswell of interest in the landscapes we have lost, or are losing, and I hope that in some ways the journal addresses this and raises greater awareness of these issues. My overarching ambition is that our name becomes synonymous with landscapes of loss, and that we can re-enchant, and re-mythologise these places as an act of both commemoration and preservation.

GER: You have a piece in the journal about Eynhallow, in the Orkneys. Back in 2017, we posted one of your pieces, Lost British Landscapes, on Unofficial Britain. It looked at Doggerland, the former land bridge between the east of England and Europe. What interests you in particular, as a writer, about submerged places?

BN: Overall, I do have this odd passion for landscapes of loss, or those places that have slipped between the cracks of history. I think for me, it has roots in our collective memory, those lost narratives, or forgotten and abandoned places that once had cultural value or some central significance in society, which for whatever reason then dissolves or evaporates from external pressure of war, disease, societal collapse, or a variety of other reasons.

Doggerland has particular fascination for me as it is a place that may still hold many secrets, submerged as it is, deep under the North Sea. Archaeologically speaking, it is relatively pristine, but over the years, deep dredging and oil pipeline activity has upset and fragmented some of its artefacts which have been dredged up for over a century now, and so its history has almost certainly become muddled and disarticulated.

Submerged or deluged lands have a central place in almost every country’s mythology and consciousness, and this has a fascination for me as it is a powerful theme that still resonates with us.

Again, I believe that floods and deluge are hard-wired deeply into our collective psyche, and that is probably an echo from a post-Ice Age mentality – it has tangible links with trauma and survival. There is also the enticing possibility that submerged places will reveal elements of our history previously unknown to us. Even as we speak, there is massive glacial retreat at the ice caps and beyond, and artefacts are appearing in landscapes that we had not realised were occupied by humans more than 30,000 years ago.

I wrote about Eynhallow under a pen name, and again, this island and the wider Orkney group once enjoyed greater status, and modern archaeologists have suggested that the area may have once been an ancient capital of Britain. This theory completely inverts our notions of sovereignty, and a London-centric view of our little island, as the Orkney islands may once have been a powerful cultural influencer, far removed from any city on the mainland. It is a compelling notion, and one that has rich thematic territory for me as a writer.

GER: Echtrai mixes non-fiction with fiction and poetry – it’s a blend I use myself in most of my books to get across both how a landscape feels, and how a landscape is as much a story as it is a physical entity. What appealed to you about this mixture in relation to the subject of lost and abandoned places?

BN: We wanted as much as possible to explore marginalised landscapes in more creative and interesting ways. I particularly wanted to challenge the more orthodox approaches to landscape writing, and bringing together a variety of authors from the academic to the experimental, to the poetic enables us to have a broader voice, and a wider perspective, and this in turn will have a greater appeal and crossover potential, exposing the reader to work that perhaps they may never have seen before.

We all experience and read or ‘decode’ the landscape in a variety of ways, and no two people will feel the same way about the places they have encountered. I think that is what makes it interesting. From a personal perspective, I write my more incantatory pieces based upon a deep spiritual connection with the many voices of the land itself, and the net result of that is a kind of hybrid of historic fact, and an idiosyncratic romanticism that fuses into something that is hopefully engaging and interesting to read.

I like that you mentioned how a landscape ‘feels’ – it is one of those intangible, ineffable forces that is almost impossible to articulate, yet as creatives, we are endlessly compelled to explore.

For future editions of Echtrai, I hope that we attract brave and innovative writers and artists and have their work and voices heard by a wider audience. Having a background in the visual arts, I have always been interested in the work of visual artists, and how they interpret marginalised places, and we have some very interesting and exciting work coming in as we speak.

To get a copy of Echtrai, click here.