Unofficial Britain is pleased to host new fiction, for those with time to spare for a longer read.

Unofficial Britain is pleased to host new fiction, for those with time to spare for a longer read.

Today, a short story by regular contributor Gary Budden…

LOCATION: Blean Woods, Kent

Dieback

Off the path, the forest sways and swarms with silhouettes. I half-remember these shadows, and will my eyes to be tricked. Loose branches are strewn about. I step on one and the crack of wood is the crack of rifle-shot. The air stinks of heritage. Where is Helena?

I look at the sign. Squinting, I read:

Respect – Protect – Enjoy

With a furrowed brow I triy and focus. I’m on pause, standing alone in woodland pointlessly checking my phone and re-reading Helena’s day-old messages:

the opportunity to liberate the mundane!

write new histories and reclaim the future!

She texts a good game and I get swept up in her rhetoric, wanting to believe in a life outside the city. Helena has a tattoo of a thylacine yawning a marsupial yawn on her right shoulder. She’s not Tasmanian, but has emigrant family in Sydney.

I place my phone back in my pocket and scan the foliage for possible photographic opportunities, perhaps something of interest I can send her way for the project. No-one knows I’m here, bar her. I want to prove I am here. I exist in a permanent past-present tense; I remember during the act and stand outside of time. Frankly, it’s exhausting.

My head aches in the bright late-May sun. Green-filtered light dapples across my clothing. I consider getting an eye test in Specsavers and gulp warm water from my bottle. Sylvan silhouettes flicker in my peripheral vision and my skin fees like dry concrete.

The sign, attached to a wooden post rammed deep into the English soil, is laid out in a tasteful and informative arboreal font. The Butterflies of Blean. I peer at an identity parade of butterflies and moths; pearl-bordered fritillary, purple hairstreak, white admiral, speckled wood, silver-washed fritillary, gatekeeper, ringlet. The rarest of them all, the heath fritillary, there it is! Right there in front of me, brazenly flaunting its finite nature, twitching its antennae as it perches on the top of the sign. I suppress the urge to crush its impossible body and reached for my camera-phone.

Respect, protect, enjoy.

Too late. It flutters off impassively, leaving me alone once more, rooted to the spot. A pair of magpies screech their ratchet screeches, abrasive, unpleasant and smug. There’s a buzz of crickets like a high-pitched generator and a slight shimmering heat haze making sure I know this is the beginning of English summer. Enjoy it while it lasts.

Earlier I spotted a jay and was briefly happy, its pink, brown and blue plumage splendid in the golden light. Digesting the information on the sign, I wonder who’d been contracted by Kent County Council to create it, what fonts they had chosen and why; before the sign I was taken on trips through these woodlands as a toddler, before all the butterflies died, with my father. I read the softly reassuring text; the heath fritillary had been saved by coppicing. Nearly destroyed by humanity, then saved by it. I wish it the best of luck and carry on my way along the Big Blean Walk, the ouroboros route of twenty five miles, through eighteen interpretative panels of butterflies, rebel risings, heaths, woodpeckers and coppicing. Only a few others seem to be travelling this path. I remind myself it’s a school day, a work day, that it requires a degree of luxury to be able to step outside your own life for a while.

A few bounding Labradors and their elderly owners are the only other non-woodland beings I’ve seen on the path and I didn’t stop to chat. I’m bad at small talk and today didn’t feel the day to practise. At any rate, those dog-walkers they looked unconcerned about the dieback. Maybe they didn’t know?

Seeing the butterfly made me feel melancholy and I questioned what the hell I was doing here. I’m conducting spurious research for a project with Helena, the coastal artist, drinking partner, sort-of-friend. Thylacine-shouldered and just-about-bearable when drunk, she is an ex-vegan and an enthusiastic smoker of cheap tobacco. We’re both, of course, eco-conscious. It was easy living in the city.

I’d failed to create a miniature wildflower patch to attract bees in my small square of allocated green space in London, but the potatoes were doing well. I have this constant feeling the world is ending and can’t decide whether to be celebrating or terrified. That fritillary, it reminded me most species on the planet, the majority that ever existed, are now extinct. When I discussed this topic with Helena, she’d point to her shoulder whether the tattoo was exposed or not. This, though, this was our fault.

I am writing the text and she’s providing the imagery for a project we can’t decide the title of. I was in favour of Blean on Me, but she was not a fan. This is serious, she said.

I’m here to take a few photographs, though I lack a proper camera. They’re going to be visual prompts, not the finished product. That’s Helena’s whole are. I lack the eye.

I’m here to soak in the ambience of the Blean. I’m here to write cramped notes in a fraying notebook, feel the place and its history. Kent, a county dozing, and paralysed by the great city to its north. A county densely populated and zig-zagged with roads, yet content to revel in bogus notions of rurality, woodland, sighing seas, boredom and The English.

Helena and I share our jealousy of Sussex and Wiltshire. They flaunt their long-men, their giants and chalk horses, leaving us with mundane Roman remnants and Saxon shore ways. I am so bored of the Romans. We both came of age here before joining the great exodus to the great city where I’ve spent a full decade in the sprawl north of the river. Those south metropolitan areas are too close to home, too close to the indifferent shingle beaches where we sank cider and smoked ourselves into mush. Too close to treacle-slow bootfairs and frustrated fights on provincial high streets, to these memories of woodland that I’m now sweating through. No fritillaries in the city, none I knew of. There’s plenty of birdlife though and I’m more enthusiastic for the avian than the insect. Why am I here? We’re trying to build our own archipelago, to escape life during wartime. I’m not a twitcher though.

The term ‘twitcher’ often gets misused, the ornithologically-challenged applying it to any old Sunday stroller out on regulated marshland, indulging in a brief respite as he or she binoculars gadwall, teal and tufted duck. TV personalities and competent writers talk about the therapeutic qualities of the bird world. Enjoy it while flocks last, and so on.

I have a terrible attention span but the birds can hold it. I romanticise this dwindling idea of nature, surrounded by concrete and firing pollutants into the sky. I try and recycle and my onion peel goes straight into my compost bin that sits next to my failed flower patch. The last time I checked it was crawling with those fat orange Spanish slug. I feel constant iron-weight pressure on my chest – this is what we want to explore, Helena says.

I wear an RSPB badge as affectation and count Chris Packham as a British hero. That gets laughs at parties. I myself toy with the idea of a tattoo, of an as-yet extant species, the narwhal maybe. I often dream about narwhal pods in ice-clear Greenland water. But Helena, for some reason, has her marsupial fixation. After her trip last year to her relatives, she bored me for two hours with digital images of wallabies and sketches in her book of wombats. I’m very much on the northern-hemisphere side of things when it comes to nature. Once, sweating in the terrible heat of Cartagena, the flocks of pelicans felt like an import from someone else’s story. An iguana defecated from a tree near my head and I thought of city pigeons with rotting feet and lit a cigarette. Helena wants me to visit the antipodes with her but I hate Australians.

I half-ignore odd facts about prime twitching spots being, now, at sewage treatment works (millions of insects), landfills, at the open sores in the land. It’s hard to accept that species can adapt. I’d rather they fade and die than submit themselves to such indignities. Yes. There’s something, there, to write about.

Birds appear everywhere, on coffee mugs, in children’s literature, on damp tea towels, logos for new internet start-ups. They form the shapes assumed by hand-crafted jewellery in the bespoke boutiques of the great city, they adorn the bodies of those unable to identify redshank or bar-tailed godwit. The Big Blean Walk had its fair share of opportunities for bird-spotting, nothing too glamorous, but it’s comforting and real. Article hopping online yesterday, sipping coffee, I noted a new species had been discovered in the bustle of Phnom Penh. It was colourful.

Between the fourth and fifth signs, after my butterfly stop, I wander off the path into the undergrowth, stepping through the bracken and ferns, trying to reach a towering ash tree that is, as yet, unaffected by the dieback. Panic sets in, the sweats, trembling bowels, fungal skin, visions of poorly armed trade unionists being gunned down by red coats, almost-Victorian blood leaching into the soil, a bounding scarlet lion, Woodsman butterflies watching hopefully for the coppicers to get back to work. The crack of wood the crack of rifle-shot. I see a new Messiah’s corpse laid out in the pub of all pubs. I have leprosy. I’m rotting from the inside out and running pigs through the old forest. In the leafy gloom I bear witness to a giant boar-being rise, angry and confused, the product of a Man of Kent who did his best to fight against this dieback. Imagination withered by tarmac. This is to be the theme of the book Helena and I are half-heartedly working on. We trip up on funding applications and crowd-funding projects that are still at the discussion phase. Perhaps, she suggests, our aims are too diffuse. This isn’t what people want to hear about. Blean lacks the glamour of a narwhal or a thylacine. Today, I have to agree with her.

Lately I dream in green and concrete, of unnoticed atrocities in the Stratford Westfield shopping centre, of Messiahs rising in the dense wooded Kentish heartlands, of a disenfranchised army of wodwo looking for a leader, Grendel hiding in the reeds on Sheppey. That and the narwhal. Helena dreams of marsupials, salt water and burnt piers, of glittering retrospectives organised after her untimely demise. You could write my obituary and use my legacy to further your own career she said to me once.

I return to the path as a greater spotted woodpecker bangs its skull into an ash tree, getting back on the heritage trail. Trembling hands slowly right themselves and my sweaty skin dries in the sun. I check what year it is on my phone. No messages, no leprosy, no gunfire. I’m disappointed.

Chalara fraxinea. The fungus jealous of the success of its cousin that massacred the elm, is staking its claim. For my part, I’ve had to relearn what the trees are, no-one really knows anymore, we are city people and trees are furniture. Is the ash native, and does it matter?

A chance encounter with my childhood in a second-hand bookshop provided me a cut-price opportunity to rekindle some of that pre-teen knowledge. I found a complete set of the Readers Digest guide to the natural flora and fauna of the United Kingdom, woefully out of date (1996 reprint, first published 1981). Nostalgia poisoned my chest as I looked at the inaccurate illustrations of pine martens, willows, heath fritillarys and red breasted mergansers. I had to have them. How much a pop, for the six? £2.50 each. The whole set a mere fifteen quid. The one about British mammals, with its folksy cover of a badger family, said that escaped red-necked wallabies had established a colony in the Peak District. Helena was happy when she heard this and proposed a trip. I’ve never been to the Peak District.

When I looked up the entry on the ash tree, the book hadn’t heard of dieback. Then it was a bad fever dream of the forest, mere gossip. In the nineties I missed so much, there were different blights and new roads to contend with. The roads won, so now is the time for fresh loss and new concerns. I mull all this over and rub spore flecked skin, stroke my fungal beard, and continue along The Big Blean Walk.

*

I sit on a rotting log a few feet off of the path for rest, water and a cigarette. I wipe my moist forehead and swat away buzzing flies, thumbing through my copy of The Hollowing I’ve brought it with me hoping for an illuminating passage to leap from the page and give this day some sort of structure. These psychic maps of the woodlands were laid out over many novels by a Man of Kent. I entertain the fancy that the archetype started here. Theories of the wildwood are pervasive, appealing and untrue. On this trip, with hardly any other humans sighted, it’s tempting to delve into a fake nostalgia for a Greenwood that never really existed. It feels, today, that it could be an antidote to whatever it is I object to. Messiahs, lepers and machine breakers all found some brief respite in this place. Today the woods are a neat pair of parentheses, a bit of breathing space in this ongoing narrative I like to create for myself (hence the bad photography, the Twitter updates, the sense of shame).

I scribble free-associative notes about the hodd, Robin in the Greenwood, (though he was a Northerner), General Ludd, the fair folk, eco protesters, Anglo-Saxon and Celtic folktales, the dieback. I can see link between all of these things but a fungal rot has set in and the dots won’t join. I try to break this formless green mess into bite-size chunks, reducible to one hundred and forty characters, digestible snapshots, but the ideas and images resist. I try and pin them down like a Victorian entomologist arranging his butterflies. No luck.

The magpies continued their metallic screeching and the sun pounds down without remorse. My phone suddenly buzzes. Helena.

Sorry haven’t been in contact phone died. On way. Meet Red Lion?

*

I sip my cold lager in The Red Lion in Hernhill. It’s all places and every pub at once. Two old men with beards in need of a trim sit and murmur at the bar. The barmaid looks bored and fiddles with her phone, polishing the already gleaming pumps, staring into vacant space. On the wall hangs a faded image of a vixen. If I exited this pub I could, with a bit of mental effort, exit into a different county, a new postcode, rural Britain untainted with personal biography, with the chance to indulge in some mere reportage.

I sip my cold lager in The Red Lion in Hernhill. It’s all places and every pub at once. Two old men with beards in need of a trim sit and murmur at the bar. The barmaid looks bored and fiddles with her phone, polishing the already gleaming pumps, staring into vacant space. On the wall hangs a faded image of a vixen. If I exited this pub I could, with a bit of mental effort, exit into a different county, a new postcode, rural Britain untainted with personal biography, with the chance to indulge in some mere reportage.

I abandoned The Big Blean Walk halfway through to meet my partner; the twenty-five miles would, anyway, have proven too much for my casual footwear. I rest blistered feet, snack on dry roasted peanuts that dry my throat and think about my trip back to the great city. I check the time and wait for Helena. I doodle a narwhal fighting a thylacine in my notebook.

Finally she arrives, black rucksack strung high over her shoulder blades, tattoo on display. Her large sketchbook is clutched hard and she’s mildly sweat stained under her left arm. Straight to the bar for a pint of cider. She sits down.

‘It doesn’t work. Our aims are too diffuse,’ I say after a while.

‘What doesn’t work? We’ve got everything we need here. This is home.’

‘I know, well you’d think so wouldn’t you, but I’ve been walking the woods today and there’s just too much . . . ’

‘Too much what?’

‘Well, the more I start looking, too much history. Too much information. Too much everything.’

‘That’s the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard’. She grins and sips her cider. ‘We form our own archipelagos, you know.’ Her words bring back memories of a trip to the Scilly Isles in `93 and the sighing mass of the Atlantic.

‘Let’s sink these then head back out there’.

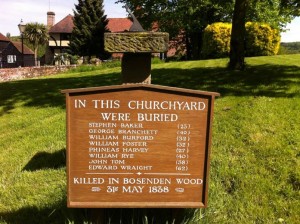

And so we do and things come together fast. We visit Bossenden Wood, where those disaffected labourers fell in 1838 and we talk of how this links to General Ludd, Robin, the wodwo, all the way back to the green man. A bit of reflexive mental effort and the dieback can be fought off. I find my patience again, without the need to document everything every five minutes – sacrificing my camera to really look, jettisoning pithy soundbites to really stop, think and reflect. I thought I have no time. I have all the time in the world. Why am I here? Because I want to be. Because, for us, it’s important. We form our own archipelagos and plant new bio-diverse forests. If the old stories are dead, we’ll raise and nurture some new ones.

We walk The Big Blean Walk, and we find where we thought the lepers had been back under Norman rule. Helena excitedly talks about the age old association of green with society’s marginals, outcasts (voluntary or forced), the appeal it still holds over people, what attracted that Man of Kent to write of his rising boar-man in the Kentish heartwood, the raves we’d been to in this dwindling forest, the tree-people, activists, Tories, ramblers, hikers and us.

Helena, equipped with a camera suitable to the job and a working botanical knowledge finds the ash trees and we find the dieback, we record what we see, don’t simply regurgitate the raw data back out into the world but make notes, come up with a structure, decide what we will do, can do, with this swirling mass of information in what seems a dull and somnambulant part of the country. There’s no need to force the connections, they’re there, the roots go deep, it’s exciting and gives us a reason to leave the great city. Dead books come alive, their continuing relevance made suddenly clear. If we look, we there is always something to care about and be a part of. The leprosy fades. Birds and butterflies are in the trees. There are deer here, somewhere. We step off the path and head into the undergrowth, ignoring the signs.

Respect, protect, reconnect.

This is how we fight the dieback.

Gary Budden is co-founder of independent publisher Influx Press and assistant fiction editor at Ambit magazine. He lives in London.