LOCATION: The Firth of Clyde, Scotland

LOCATION: The Firth of Clyde, Scotland

This is an extract from Angus Farquhar’s photo essay in the new book St Peter’s, Cardross

I set up NVA, an independent arts company (the letters stand for nacionale vita-activa, meaning ‘the right to influence public affairs’), and was fascinated with making art in special locations, rather than theatres, galleries and concert halls.

At NVA, we created the walk-through performance ‘The Storr’, on the Isle of Skye, inviting some 6,500 people to interact with the presence of the landscape over the course of 42 nights.

Following the illegal invasion of Iraq, we founded the Hidden Gardens, a sanctuary garden built out of wasteland at the back of the Tramway arts centre in Glasgow. And we took The Speed of Light, a physical celebration of collective running, from Edinburgh and Salford to Yokohama and the rehabilitated industrial landscapes of the Ruhr.

I was looking for a new direction, for a plan that moved NVA away from large scale but transitory live performance, and focused on permanence. And then one snowy January morning eight years ago, it popped into my head: St Peter’s.

I knew that there was an abandoned building, somewhere outside Glasgow, where young priests had been trained in the 1960s. Braving the winter cold, I set off with a hardy group of colleagues to visit it. Parking in a rutted layby just beyond the small village of Cardross on the Firth of Clyde, we walked into the densest forest of rhododendron you can imagine.

We soon lost all sense of direction. We found an old castle keep and the remnants of a walled garden, but no sign of the legendary ruin of St Peter’s Seminary. Undefeated, a week later I tried again with my NVA co-director Ellen. This time we spotted a huge harled wall rising up through mist. Slipping through a broken fence we entered one of the most imposing structures I have ever witnessed.

It took time to figure out what I was looking at when first wandering round the main seminary block. The level of destruction was so complete in places that it was impossible to read how interiors were framed, levels connected or screening demarcated different spaces.

In the teaching block and crypt the piles of detritus were overwhelming, so that entry was not possible on some floors. I couldn’t think of it as a working building. It was disconnected from the grainy images of young students in black cassocks scurrying to mass, cleaning floors or relaxing in glass-sided rooms.

Gradually I put a timeline in place starting with two young architects, who, like many before them, were unafraid to quote from buildings they liked and other architects that they admired. Who introduced subtle historical and geographical references into the designs in a way that was true to themselves and their passions.

Gradually I put a timeline in place starting with two young architects, who, like many before them, were unafraid to quote from buildings they liked and other architects that they admired. Who introduced subtle historical and geographical references into the designs in a way that was true to themselves and their passions.

One of Andy MacMillan’s family members recalled visiting as a small child and being given a bottle of ginger by kind nuns at the back of the mansion house. Playing in the woods, she remembers the image of her dad standing on the driveway in the distance, his arms waving up and down as he remonstrated with the site foreman.

It must have been a battle to ensure that the more experimental edges in the plans weren’t rubbed out through a protracted and difficult construction period.

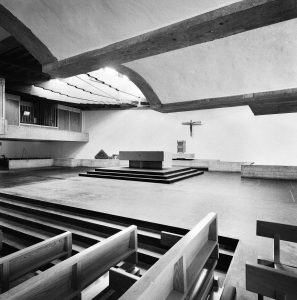

When I first visited, half of the floating glulam beams that radiate out from the curvilinear wall behind the main altar were still intact. On a good day with the sun high in the sky, sharp geometric shadows and shapes were cast onto the floor and walls of the sanctuary and chapel. It came to life as a vast Constructivist sculpture or Suprematist installation.

Suddenly the artistry of the original plans came to the fore and a charge of discovery ran through me. Witnessing the main spaces transformed by light and shadow confirmed reports from former priests and students whose celebration of Mass was sometimes enhanced profoundly by the setting.

Early on our creative team decided that the restoration of the laminated timber beams, roof and original ziggurat roof light would be a priority.

I began to build a picture of how the components of the design functioned together. Kilmahew House was the destroyed nineteenth century centrepiece and nodal point around which the new buildings were composed and choreographed.

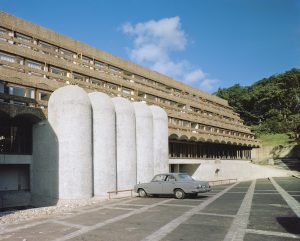

The stone structures and the retaining walls allowed the site to sit up like a raised garden above and within the mature woodland estate. The main block was formed by a series of stepped floors elevated on fine piers. Cantilevered above the refectory and the chapel, the simple study bedrooms punctuated the outer walls en masse like a honeycomb, generating the large internal voids of the refectory and sanctuary. Floating staircases, cast in-situ out of concrete, linked the progression of floors together.

Isi Metzstein described his design as being ‘against dogma’, creating a dizzying array of non-standard spaces.

Against the dominant central plan axis of the chapel and refectory there were a series of informal spatial sequences. Ten side chapels clasped the outside of the chapel like the fingers of Christ, also referencing agri-industrial and military silos.

The huge curved flanks of the load-bearing apse wall gave shape to a rising ramp that dramatically linked the sacristy to the sanctuary floor. The external wall was rough harled in the style of an old baronial castle with little light penetration except through small irregular windows that punch through to the crypt. The careful control of daylight echoed Mackintosh. Fragments of red, green and orange window glass represented the only use of colour throughout.

Undressed, fair faced timber board marked concrete walls; glass and wooden framing were used in combination to create different rhythms throughout, dominated internally by the wave-like repetition of multiple barrel roofed vaults.

To some seminarians this reflected a neo-medieval austerity; to others the severity of a war-time bunker.

The buildings were organised around the movement and procession of the student priest throughout the day with open cloisters continuing the traditions of monastic retreat. A shallow moat recalled historic defences refracted through Japanese minimalism. Diverted spring water ran between levels down a monumental iron chain that would not have looked out of place in the Clyde shipyards.

The destroyed sanctuary roof light and the main block (when seen in section) echo the ziggurats of ancient Mesopotamia, referenced as one of the earliest ‘social’ architectures. The teaching block was by contrast a leap into the future; a spaceship flight deck, drawing on the bold cantilevers of Lloyd Wright to arc over the foundation walls of the demolished Victorian house, allowing panoramic views down to the canopy, gorge and river below.

All pieces of a complex puzzle, but for me it was by visiting the Couvent Sainte-Marie de La Tourette that the overall design finally fell into place. Le Corbusier’s Dominican Priory, completed seven years before St Peter’s College, rises at the head of a valley set in open countryside near Lyon. Key elements from the brutalist canon were transposed to re-appear at St Peter’s.

As through a kaleidoscope, forms were fractured and reconfigured in key parts of the Scottish building. There was no pastiche, rather a direct homage to the ideological father of Modernism and one of his greatest designs.

All of these elements cohered into the design of St Peter’s and as a result it was free of restraint. Even if now it exists as a post-functional sculpture, it has life and energy and a story to tell.

St Peter’s, Cardross by Diane Watters, featuring a photo essay by Angus Farquhar, is published by Historic Environment Scotland in partnership with NVA and Glasgow School of Art. Until the 20th December 2016 you can order it from here with £10 off the RRP.