WORDS & PICTURES: Peter Riley – this is an extract from his book, Strandings (Profile Books, 2022)

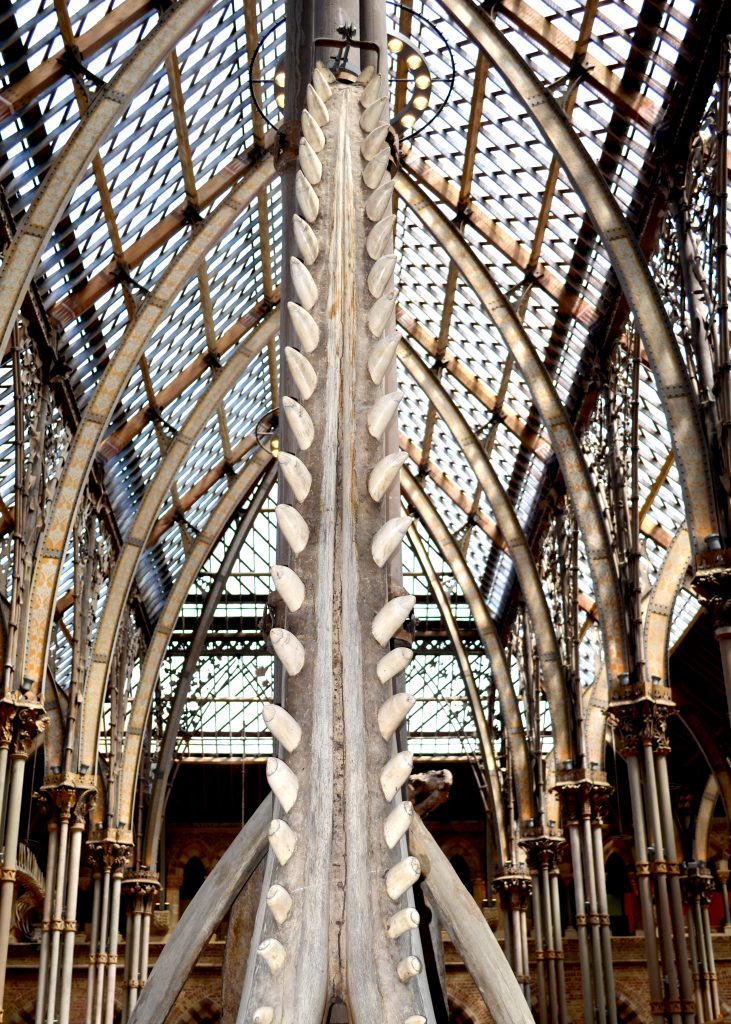

When I was thirteen, I helped a woman with blue hair load the jaw of a sperm whale into the back of a yellow Volvo 245. It only just fitted. What she’d got hold of wasn’t quite as big as the one that greets you at the entrance of the Natural History Museum in Oxford; that’s still the most enormous jaw I’ve ever seen. Nevertheless, what I helped carry was big. And heavy. Add to that the pounds of blubber and you get a sense of what we transported that morning – maybe the weight of a tall man. According to the butchers I’ve asked, it must have taken her at least half an hour to saw through. If you’ve ever handled a piece of whalebone, you’ll know how durable and solid it feels – like reinforced, triple-weighted pumice. In the case of a sperm whale, it’s even sturdier, needing to withstand higher water pressures than in other, shallower-diving members of its species. The blue-haired woman had accomplished this at night, alone, and in the steady Norfolk rain.

The sperm whale in question had stranded itself the day before on the iliac crest or hip of eastern England. Old Hunstanton’s north beach is a stretch of sand and mud that slides into the Wash, one of Britain’s largest estuaries. It was 1997, the first weekend of the Easter break, and my mum had rented a small barn just outside Holme-next-the-Sea, a nearby village that would, a year later, become known for its ‘Seahenge’ – a 4,000-year-old Bronze Age timber circle of fifty-five posts surrounding an upturned oak stump sunk into the sand.

There was a break in the rain, and the very early morning horizon already shone through a light blanket of coastal cloud. In a neighbouring field, the hares were beginning their daily boxing and sprinting. I had written ‘Gone to visit the whale’ in my neatest handwriting and left the note on the doormat.

We’d driven up from the south-west suburbs of London in a light-blue Ford Fiesta. Mum and I had recently moved into a place that stood about twenty metres from a stretch of the Windsor-to-Waterloo line. Four trains an hour. In spite of everything, it all ran fairly smoothly. I was a member of the Fifth Staines Sea Scouts, which meant that once a week I swore allegiance to the Queen and the Union Jack. I was shy and polite. My dad would dutifully pick me up on Saturday mornings and take me clockwise past Heath-row and up the M25 to see his mother in Watford. We’d eat cream of mushroom soup from a can, and everyone would say how delicious it was. My mum held down a series of jobs. She saved up enough to put herself through university – I was nine when I went to her graduation. She began working in adult education, teaching German. On Tuesday and Wednesday evenings she taught language classes in our front room to groups of adults – Tony, Robert, Reg and Sheila. They all greeted me whenever I passed through the living room on my way to the toilet. Robert once took Mum and me to the South Coast and Lyme Regis, where the fossil remains of 180-million-year-old marine reptiles regularly wash out of the cliffs.

The afternoon before I helped load the sperm whale’s jaw, I had joined a crowd of maybe fifty people that had converged on the animal. As is usually the case, one or two tried to think of ways to float it back out to sea. A man wearing white chinos had taken it upon himself to sprint back and forth between whale and surf armed only with his toddler daughter’s crab bucket. The child ran after him angrily demanding its return. The rest of us stood and watched as he tossed small amounts of water onto the whale’s head. After maybe twenty buckets, a fluorescent-jacketed man who was putting up a cordon of red and white tape informed us all that if the creature was not already dead, then it would very likely soon be. The best and kindest thing to do, he urged us, would be to leave it in peace. ‘A whale of this size’, he said, ‘once stranded, tends to suffocate very quickly under its own weight.’ The father received a smattering of applause as he re-joined the assembled crowd. His daughter continued to cry.

The next morning, the whale’s jaw appeared over the crest of a beachgrass dune, followed by a face concentrated in the effort to keep it balanced as the bowsprit of a wheelbarrow. The blue-haired woman had wrapped her prize in a white sheet that fluttered bloodily in the breeze. I knew immediately what she’d done. A butcher’s bowsaw sheathed under her arm, she wore a pair of industrial- looking rubber gloves that were now smeared in a thick abattoir slime. For a few moments she carried on struggling, unaware of the child standing just a few metres away. At that moment she was easily the most beautiful person I’d ever seen. Her blue hair was cropped short. The bridge of her nose was tanned and freckled. I stood dead still. She stopped; looked at me – inhaled a lungful of sea air. Setting the wheelbarrow down, she transferred the saw to her right hand, drew herself up a good foot taller and faced me in silence. It occurred to me that I was about to be murdered. A minute passed before she spoke.

I now know that she was part of a wide circle of cetacean body-snatchers and bone-collectors. When the whales appear, the scavengers move in. There are more than you might think. Take this hooded figure, snapped for the Daily Mail in late 2011. Notice that the jaw’s already gone. The accompanying caption explained, with some restraint: ‘Member of the public cuts off a tooth from the beached whale, which washed up on the Norfolk coast on Christmas Eve.’ By early January, a follow-up story described how local police had detained a local ‘male youth’ for subsequently posting a bill of sale on a social networking site; £5 per individual tooth (fifteen available) or £45 the lot (fifteen teeth plus eleven still in situ, plus the jaw itself). How had he settled on the going rate for a whale in 2011? There are a few considerations he might have weighed up.

First, under International Whaling Commission regulations there’s a ban on ‘harvesting’ (though harvesting really only applies to whaling proper), as well as a ban on ‘trade’, under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (that’s one he might have been cautioned for). Then there’s the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations Act of 2010, which promises up to six months in prison and an unlimited fine for this kind of activity. Contraband once, twice and maybe three times over (without a specific buyer in mind), the youth’s modest pricing reflected some challenging market conditions.

To read more about Peter and the whale, order Strandings here.

“Brave, reckless and engaging” – Iain Sinclair

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Peter Riley has been investigating stranded cetaceans and their afterlives since his teens. He lectures in American literature at Durham University, with a special interest, naturally, in Herman Melville. Strandings won the inaugural Ideas Prize for nonfiction.