LOCATION: Southeastern Rail, London, Hastings

LOCATION: Southeastern Rail, London, Hastings

WORDS: Ben Thompson

The first time I saw Tex (and although at that point I didn’t know his name, it would probably have been one of my first guesses) was at about eleven o’clock on a Saturday morning on the all-new, supersize London Bridge station concourse.

I was inwardly cursing the huge detour they were still making you take at weekends by shutting the pedestrian tunnel from the tube station, when a man wearing a cowboy hat and a Native American-style fringed jacket caught my eye. He had a couple of heavy-looking bags with him, along with a large dog – a very beautiful silvery husky – and had stopped to engage a couple of slightly worried-looking female backpackers in intense conversation. I wondered what he was asking them and smiled to myself at how exactly he seemed to fit the template of ‘the kind of person the guidebooks ought to warn you about’, before carrying my own heavy bag onto the platform.

Ten minutes later, the train to Hastings came in on time and, as I found myself boarding it one door down from the travelling frontiersman and his dog, I felt that vague sense of unfocussed inevitability which often precedes the unfolding of an improbable situation.

There was something about the spectacle of the dog’s wild quasi-lupine grandeur against the mundane backdrop of the sparsely populated Southeastern train carriage that was instantly gripping. And as we took our seats and the animal – whose name, I would soon find out, was the counter-intuitively domesticated ‘Dolly’ – eyed me speculatively from a few seats away, I asked its owner if it would be OK for me to take her picture. Tex replied robustly in the affirmative.

The moment this simple task was completed, Tex asked me to come and join him for a chat. After momentarily considering a self-consciously polite, work-inspired demurral, I picked up my stuff and within a few seconds found myself embroiled in just the kind of exchange that fosters such instinctive anti-social impulses, as Tex (who I still didn’t know was called that, but the time of my ignorance in that area was fast drawing to a close) expounded in a loud voice about how he now regretted coming to London because “All the Asian people” were very reluctant to give money to charitable causes.

Keen to head this conversation off at the pass, I asked how long he’d been in the capital, expecting an answer somewhere along the lines of “since last Thursday”.

Tex held my gaze with a look of some intensity and, after a pause suggesting a good stand-up comedian’s instinctive command of bathos, replied “44 years”.

He went on to explain that he was currently on his way to Royal Tunbridge Wells because “you meet a better class of person, there”, and having asked me my destination, responded to the answer with diaphanously-veiled contempt.

Names were exchanged and Tex explained the unlikely story of how his had been come by. He’d been brought up in Texas by native Americans, he said. Hence his current involvement in fund-raising for a planned North London-based Museum of Native American culture.

His bags contained “Indian-style” leather bracelets and necklaces, and ornate decorated leather jackets like the one he was wearing, which he was selling wherever he went in the hope of one day building this somewhat far-fetched (at current property prices, but in the aftermath of Brexit-inspired economic meltdown it may become more practicable) locus of cultural outreach.

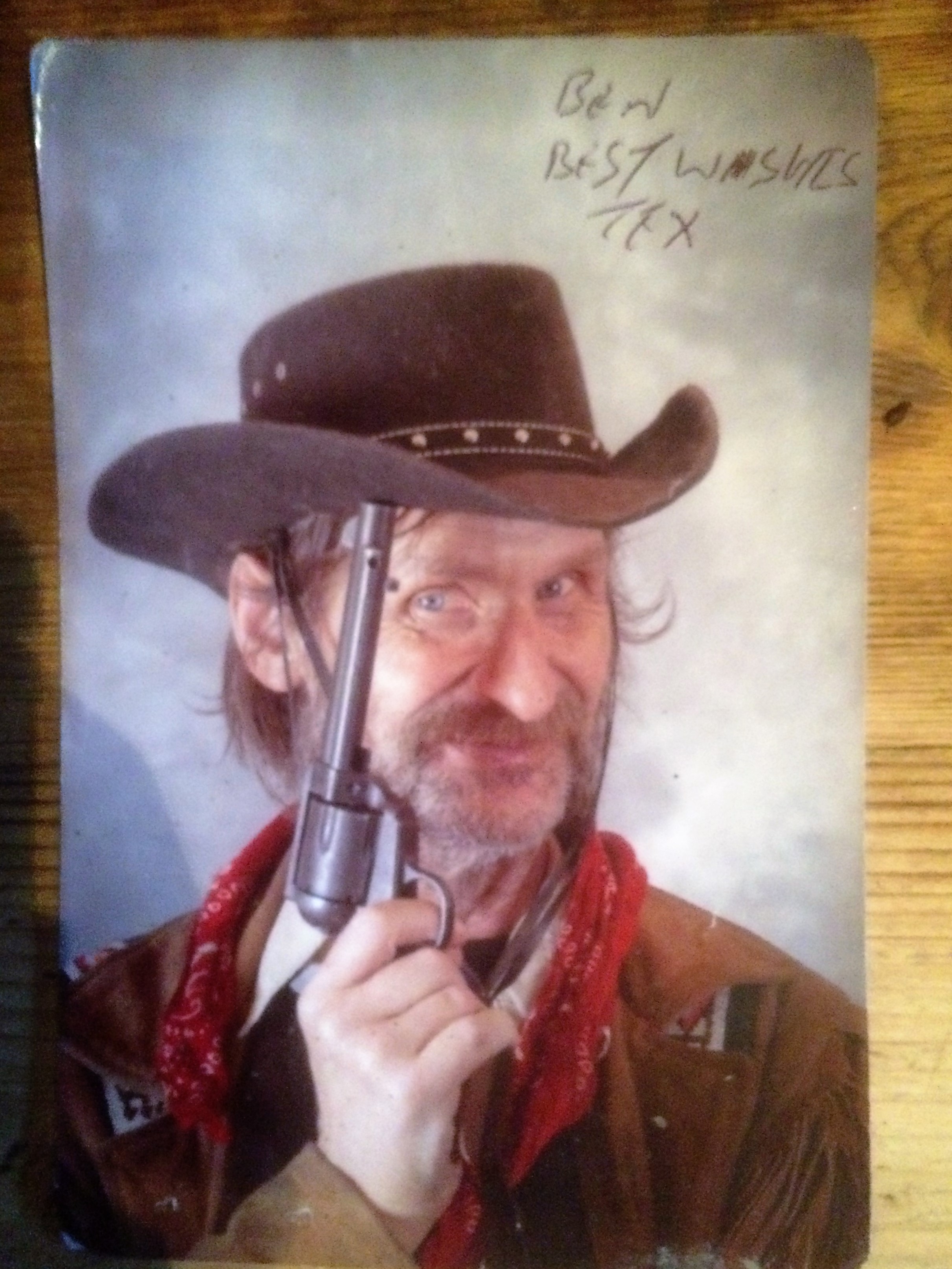

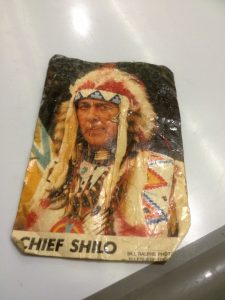

As if sensing that some evidential validation for these assertions might not go amiss, Tex produced a photograph of the “uncle” who had accompanied him over to the UK from Texas as a child, and had sadly recently died after a long spell of ill-health. As I studied this picture, with a satisfaction whose cause will soon become evident, Tex’s conversational course took another unexpected turn with the a-propos-of-nothing assertion that:

“When you go to Hastings you should get yourself a squaw – they’re much more faithful than the English women”.

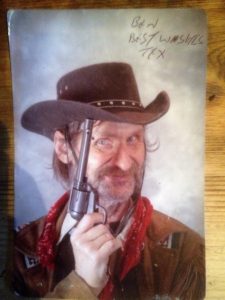

Now thoroughly convinced of the veracity of his story, I gave Tex a fiver for the cause, and asked if he’d mind me taking his picture, too. He seemed delighted by this request – as I’d expected he would be.

At this point, the train made its first stop – at Orpington – and a canine commotion bespoke (or be-barked in this case) the advent of another dog. Dolly, who had been a total pussy cat thus far, posing obligingly for photos and sitting meekly under the table, was instantly transformed into a ferocious adversary, but even her full range of intimidating snarls could not dim the luminosity of the rough diamond who now sat down at the seat opposite Tex.

His name, he established right from the off, was John, and while the can of lager in his hand gave him the initial aspect of a street drinker, he would later explain (and a couple of loud mobile phone conversations between Frant and Battle would confirm) that he’d only been obliged to get started on the day’s supply because a friend had backed out of a proposed fishing trip at the last minute.

Within seconds of his arrival, John was engaging Tex and I in well-informed (at least on his part – he certainly knew much more about this unfolding news story than either of us) conversation about shocking recent events at the North Dakota pipeline protest. From this cogent opening statement he then extrapolated to an alarming but not wholly unpersuasive theory implicating George Bernard Shaw (and by implication Jeremy Corbyn) in the discovery of Zyklon B.

This erudite – albeit not necessarily entirely factual – exposition culminated in a heartfelt plea to “whatever you think God is… personally, I think it’s aliens, but whatever, it’s all love” for help in protecting us from such existential threats.

While John was saying all this, his dog – a sweet-natured staffie called Tobias, whose slightly gruesome chronic eye injury bore blind witness to a regrettable tendency to get “munched by monsters” – was coming under heavy pressure from an increasingly aggressive Dolly. Finally Tobias’ nerve broke and (not being on a lead – John doesn’t believe in leads) he bolted up the aisle of the carriage and leapt onto the knee of a total stranger for sanctuary.

This man, who had been blatantly earwigging the conversation with that delighted sense of ‘this could’ve been me’ relief often observed in travellers who have narrowly avoided a potentially embarrassing encounter, soon overcame his initial anxiety about this turn of events, to commune happily with the anxious dog.

This man, who had been blatantly earwigging the conversation with that delighted sense of ‘this could’ve been me’ relief often observed in travellers who have narrowly avoided a potentially embarrassing encounter, soon overcame his initial anxiety about this turn of events, to commune happily with the anxious dog.

As John moved off up the carriage to conduct his urgent mobile phone business, Tex chose this moment to offer me the chance to buy a couple of somewhat weather-beaten signed photos of himself. He only wanted 5p for them, but I wouldn’t – for reasons that will soon be apparent – let him take less than a pound each, and when John reappeared and was instantly captivated (who wouldn’t be?) by Tex’s gun-toting pose (“I’ve got three guns – one of them’s a blunderbuss”) but didn’t have any money for a photo, I persuaded Tex to give him one in a 3 for 2 deal based on the extra £1.90 I’d given him.

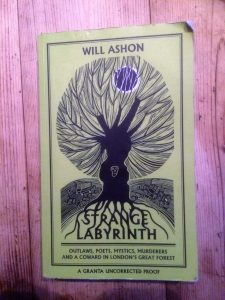

After warm goodbye handshakes, Tex and Dolly left the train at Tunbridge Wells, and John’s attention turned to the book I had in front of me on the table (as yet unopened on this journey, due to the compelling nature of unfolding events). It was an advance proof copy of Strange Labyrinth, a book about Epping Forest by Will Ashon, the novelist and former boss of UK hip-hop label Big Dada.

Following in the angst-ridden North East London footsteps of Marshland, the host of this website’s earlier city wilderness odyssey in the nearby wetlands of Hackney, Strange Labyrinth is the first of a number of projected titles seeking to encapsulate that most diffuse and inchoate stretch of urban woodland. In fact the rush to lay claim in print to London’s most extensive remaining tract of arboreal wilderness is starting to resemble the famously absurd ‘Land Rush’ sequence in the hilariously creaky Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman vehicle Far & Away.

Whether or not the words “this land is my land” ever left his lips, Ashon seems to have stuck his flag right in the most fertile terrain – just as Tom did. Strange Labyrinth positions him (Ashon, not Cruise) as the troubled love-child of Felicity Kendal and Raoul Moat, embracing the possibilities and excitement of the natural world with a city-dweller’s delight, even as he is constantly beset by comically intense anxieties about the potential for impropriety and danger (especially in the menacing shape of his arch-enemy, the dog) that runs through the woodland like the rings in the trunk of an oak.

Whether or not the words “this land is my land” ever left his lips, Ashon seems to have stuck his flag right in the most fertile terrain – just as Tom did. Strange Labyrinth positions him (Ashon, not Cruise) as the troubled love-child of Felicity Kendal and Raoul Moat, embracing the possibilities and excitement of the natural world with a city-dweller’s delight, even as he is constantly beset by comically intense anxieties about the potential for impropriety and danger (especially in the menacing shape of his arch-enemy, the dog) that runs through the woodland like the rings in the trunk of an oak.

My resistance to the current vogue for the kind of ‘nature writing’ in which nature gets the black-best-friend-in-a-shit-romcom role as facilitator of a spoilt bourgeois human’s personal growth and/or recovery process, is more or less infinite. So Ashon’s achievement in overwhelming that populous garrison with his roughneck militia of entertaining neuroses and meticulously researched historical and literary speculations (not to mention extensive and informative interviews with ex-members of Crass) is not to be sniffed at. And at the very least this book will establish him as Keith Floyd to Robert McFarlane’s Delia Smith.

But as Britain’s dwindling stock of wild spaces becomes increasingly overcrowded with charabancs of psycho-geographers – outward-bound ambassadors of that very specific social cadre defined by the writer Richard King as “The Chris Petit Bourgeoisie” – I do often wonder how the full-time denizens of those locales might feel about these iPhone-toting incomers.

So with Tex’s valiant, albeit possibly doomed, attempt to memorialise the mythic open spaces of the Wild West fresh in my mind, John’s response to Ashon’s book was a source of great interest to me.

Our earlier conversation had revealed him to be a man who spends the bulk of his time in various London woodlands, walking as many as 8 or 9 dogs at one time, none of them on leads. This heedless harbinger of canine peril might reasonably be cast as ‘The Anti-Ashon’, and yet his response to the volume he picked up from the table was entirely favourable.

“That’s a nice cover”, John observed (and he wasn’t wrong). As he flicked through the text, making occasional approving nods, John’s own long-germinating assessment of this increasingly disputed woodland terrain budded into swift-passing bloom – “It’s alright that place, but some of the ponds are minging”.

Will Ashon’s STRANGE LABYRINTH – Outlaws, Poets, Mystics, Murderers and a Coward in London’s Great Forest will be published by Granta in April 2017.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Ben Thompson is a music journalist and ghostwriter whose next publication is Lonely Boy (Heineman) the autobiography of Sex Pistols guitarist Steve Jones.