WORDS & PICTURES: Dan Carney

LOCATION: The London Borough of Redbridge

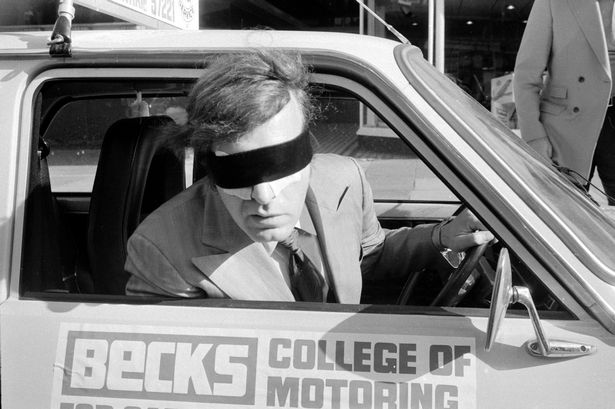

He leans out of the car window. His expression is emotionless, his side-parted hair slightly windswept. On the side of the vehicle is a logo for a Beck’s College of Motoring. Despite being blindfolded by a strip of black silk, he knows he is being photographed.

The picture is from the Manchester Evening News and shows Ronald Markham, better known as stage hypnotist Romark, before his attempt on October 12th, 1977 to drive blindfold down Cranbrook Road, Ilford, to publicise his upcoming run at the Ilford Playhouse.

There will be no injuries, but it will not go well; he will drive the yellow Renault for around twenty yards before ploughing into a parked police van.

*

Markham’s path into the back end of a police vehicle in Ilford was a varied one. He started as an auctioneer in his native northeast, hawking discontinued stock in his Oxford Salerooms shops-cum-auction halls.

Then, in 1969, came an ill-fated foray into Newcastle nightlife, when, along with his close friend, the comedian Bob Monkhouse, he launched the Change Is club. This three-floor city centre fun palace boasted hallucinogenic light shows, circular floors, and hidden projectors casting rotating backgrounds – jungles, deserts, ice caps, and mountain ranges – onto the curved walls. Markham was manager-cum-host, showcasing his growing prowess for hypnosis and adding a sheen of light entertainment glitz to the air of late 1960s irreverence and wilful surrealism provided by a suitably bizarre mix of acts including King Crimson, Ivor Cutler, and Max Wall. Petty thievery by employees, however, was keeping profits low.

In his 1993 autobiography ‘Crying With Laughter’, Monkhouse offers the view that Markham and his wife were too seduced by the lifestyle to stay on top of things. Worse came after a year, when the bank informed Monkhouse that Markham had withdrawn all the cash and fucked off. The comedian would later claim that his funding the venture to the tune of £130,000 – money he never saw again – had been the result of suggestions inserted by Markham into a stop-smoking hypnosis session. His resigned, but admiring, description of his former business partner is after-the-fact, but more entertaining for it:

“His disarming charm was that of the confessed conman, a cardsharp who declares his hand before the bilking, the dip who enquires what pocket you keep your wad so as to minimise mutual inconvenience.”

Markham then seems to have assumed the mantle of celebrity illusionist/hypnotist, surfacing next in Durban, South Africa, bearing his new portmanteau-d stage name and fronting the modestly titled ‘The World’s Most Remarkable Brain’. During this, the longest running one-man stage show in the country’s history, he was reported to hang himself before coming back to life.

A spell in Hollywood followed, where he appeared on late night talk shows and performed for Zsa Zsa Gabor. Back home, he attempted to hypnotise 1000 people at Newcastle City Hall into stopping smoking. Nothing is known about whether this was successful, although some reported feeling powerless to resist. Six women collapsed and required reviving, albeit by Markham himself after paramedics were, curiously, unable.

Next was a BBC series, ‘The Man & His Mind’, in which Markham promised to outstrip the young Israeli Uri Geller, already well on his way to becoming the UK’s premier psychokinetic illusionist. Although Markham did identify a word randomly pre-selected from the dictionary, at odds of 1 in 130,000, ratings were poor and the programme was canned.

He then combined a spell as a Harley Street hypnotherapist with higher profile paid gigs for professional football clubs. He hypnotised players, cursed opponents, and at one point announced a hex on The Sun for trying to expose him as a fraud.

In 1976, he was flown to Munich by The Daily Mirror, to hypnotise Yorkshire heavyweight Richard Dunn ahead of his world title fight with Mohammed Ali. Markham went one better, cursing a bemused Ali to his face after unexpectedly encountering him in a hotel. While this proved fruitless, Ali beating Dunn easily, the hypnotist was adamant that the collapse of the stage at the pre-fight weigh-in was due to his efforts. He pitched up in Ilford, ready to demonstrate his mastery over the primary senses, the following year.

*

To fill in some of the gaps, I visit the Redbridge Museum & Heritage Centre at Redbridge Central Library in Ilford, around 800 yards from the site of the now-defunct playhouse, in order to look at local press archives.

A helpful assistant sets me up on a microfilm reader. It isn’t long, however, before I’m distracted. Local newspapers from 1977 are a wormhole into a more febrile Britain, a relatively bloodless location such as the outer London borough of Redbridge presenting a gamut of dangers.

All the following comes from publications a month either side of Romark’s driving exhibition:

…Redbridge pet shops are alerted by health chiefs following a case of “rat bite fever” from a rodent purchased in the borough.

…Four nursery children in South Woodford are hospitalised after eating poisonous berries in the playground.

…An eight-year-old Chadwell Heath boy is found playing with an unexploded World War II bomb.

…A cyclist shoots a twelve-year-old boy in the back with an airgun, an apparently motiveless attack leaving the child needing stitches.

The danger isn’t just physical; an Ilford shopkeeper claims to have been hypnotised by a mysterious customer into handing over £1700 (sadly, the description of the perpetrator, heavily built with a thick Italian accent, rules out Romark). It’s easy to imagine, given the peril constantly stalking the local populace, how a stage hypnotist ploughing blindfold into a parked police van may only merit a cursory paragraph.

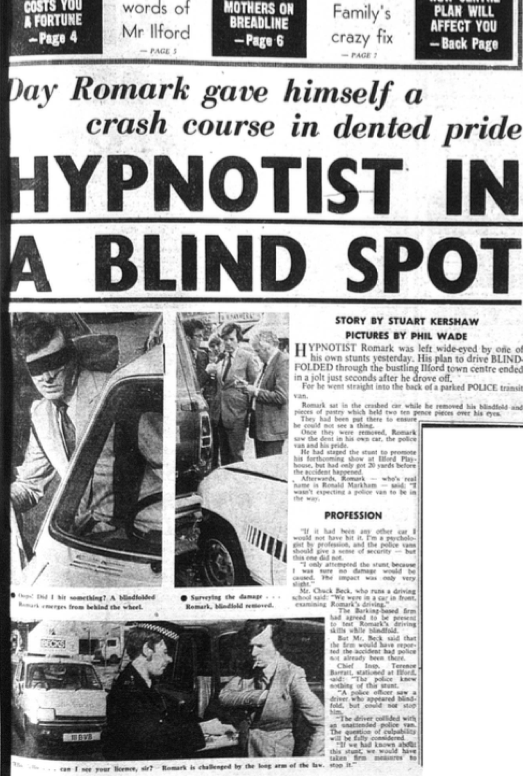

But then, on the cover of the Ilford Recorder dated October 13th, 1977 – there it is: “HYPNOTIST IN A BLIND SPOT – Day Romark gave himself a crash course in dented pride.” A rundown of the event reveals nothing new, but there are longer quotes from the man himself:

“I wasn’t expecting a police van to be in the way… If it had been any other car I would not have hit it. I’m a psychologist by profession, and the police vans should give a sense of security – but this one did not. I only attempted the stunt because I was sure no damage would be caused. The impact was only very slight.”

There’s a triptych of (possibly staged) photos, showing Markham first exiting the car blindfold, dispassionately surveying the damage while being interviewed by a journalist, then talking to a policeman, smoking a fag and looking pissed off. The police van is one of the old-style Black Marias. The Beck’s College of Motoring logo is visible atop the crashed car; it is revealed that Chuck Beck, proprietor, was also on the scene, examining Romark’s driving from a car in front. He assures the paper he would have reported the accident had the police not been present. Chief Inspector Terence Barratt, however, is unimpressed:

“The police knew nothing of this stunt. A police officer saw a driver who appeared blindfold, but could not stop him. The driver collided with an unattended police van. The question of culpability will be fully considered. If we had known about this stunt, we would have taken firm measures to stop it.”

The following week’s Ilford Pictorial provides more. The following Monday, Markham visited Romford’s Cardrome Learner Centre to conduct a more controlled stunt in a dual-control car. Accompanied by Len Beisser from Beck’s, he achieved full marks on a two-minute blindfold test. He had driven unaccompanied in Ilford, refusing to test the route beforehand – “I just know what I can and can’t do” – and that he had planned to drive for at least eight minutes. Beck, meanwhile, suspected police interference – “The police deliberately tried to jeopardise him, instead of stopping him before he started off” – adding that the van was parked in contravention of the Highway Code: “… five feet from the kerb, on a double yellow line, at a bus stop.”

Markham changes his story of what happened in Ilford, saying he had run into the police van deliberately, in response to their harassment. This contradicts what he is reported to have said on the day both immediately after the accident – “I didn’t know the police van was there” – and half an hour later after being questioned by the police: “I knew the police van was there, but carried on because to me it represented security, not danger.”

The accompanying photograph shows the aftermath from a wider angle. A policeman records the details, while a suited Markham solemnly inspects the damage. This looks minimal, suggesting low speed and gentle impact.

Two details offer new insight. Firstly, waiting behind, travelling in the same direction, is a 129 bus showing the destination Ilford Station; if correct, this means Romark was driving south towards Ilford town centre, where the station is located.

Then, on the right in the background, is a distinctive-looking first floor window. A speculative cross-reference with Google Street View show that the window, surprisingly unchanged, is still there; the photo was taken in front of the junction of Cranbrook Road and Park Avenue, a few yards on from the Playhouse. With rising excitement, I realise that I have geo-located both the direction and the start and end points of Romark’s journey.

Next comes yet another novel detail – page 76 of the following week’s Recorder is a short article detailing Markham’s plans to flout a Greater London Council regulation prohibiting the use of hypnotism in a licensed establishment. He cheerfully explains how he will get around it, throwing down the gauntlet:

“I have developed a method to hypnotise people without them knowing about it. I welcome anyone from the GLC to attend the show so I can prove what I mean. I am determined to demonstrate hypnosis.”Playhouse director James Cooper assures readers he will be “watching very closely to ensure the law is not broken.”

A further search of the British Newspaper Archives reveals nothing else about the drive itself, bar a wider-angle shot in The Daily Mirror that confirms the location. New information is, however, provided by the fact that the same publication, possibly trying to recoup the money they spent flying him to Munich a few years earlier, are much more interested in the punishment than the crime.

On 19th September 1979, almost two years on, they report Markham appearing at Snaresbrook Crown Court, charged with reckless driving. The hypnotist denied the charges, but prosecutor John Leslie was damning: “It would be hard to think of a more reckless thing to do in a busy street.”

Amazingly, Markham is reported to have denied, immediately afterwards, even causing the accident, or even being blindfolded: “What blindfold? The marks on the van were not caused by me.”

Three days later, they report that Markham was found guilty – fined £100 and ordered to pay £220 costs – and criticised by David Berglas, a senior member of The Magic Circle, for revealing when cross-examined how he had planned to “see” while blindfold:

“Romark not only let down the rest of my profession but he let down the public, which enjoys being led to believe that a fairly simple trick is done by supernatural magic.”

Markham, however, was defiant:

“It is immoral for magicians to pretend they are anything other than people who perform a good trick.”

Sadly, no fresh insight on whether he knew the police van was there, or crashed into it deliberately, is provided.

*

I decide to go to the site of the event to stand in the exact spot where Romark ploughed into the van, the angry shouts of policemen and blocked motorists in his ears.

Outside the old Playhouse – a beautiful art nouveau gothic church building – early on a cold April morning, it strikes me that Romark’s plan to drive for eight minutes would have taken him a reasonable distance. At an average speed of, say, ten miles per hour, this would have been around 1.33 miles. Round the gentle leftwards bend into Ilford town centre, past the old Pioneer indoor market, about halfway up Ilford Lane towards Barking.

Even for a straightforward magic trick, this would have been pretty impressive, although it is undoubtedly for the good of the pedestrians of 1970s Ilford that it didn’t happen.

I step out into Cranbrook Road, and stand at the collision spot. To my disappointment absolutely nothing happens. No discarded piece of black blindfold cloth flaps forlornly at the side of the road. There are no new frequencies, insights, or answers.

But I don’t mind. For what little I have unearthed now means that there are new questions to ponder, new uncertainties to enjoy. And maybe, the unanswered questions make it more interesting in the long term.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Dan Carney is a musician/writer from northeast London. He has released two albums via Lo Recordings, as Astronauts, and also works as a composer/producer for TV and film. His music has been heard on a range of television networks, including BBC, ITV, Channel 4, HBO, Sky, and Discovery. He has also been involved in academic psychology research, authoring a number of articles about cognitive processing in genetic syndromes. His non-academic writing covers a range of subjects, and has appeared in publications such as The Blizzard, McSweeneys, Elsewhere, and The British Psychological Society Research Digest. His other interests include walking, hanging

around in cafes, and spending too much time thinking about Tottenham Hotspur.

Twitter – @astronautheart

Instagram – astronauts_uk

Interesting on many levels, including why is it interesting? I vaguely remember this guy.