WORDS: Gary Budden

The sky is moody and grey. We park up in a windy carpark by Reculver towers, see two sand martins dart by towards the sandstone cliffs. They’re specific to this place and newly back for the summer.

I look out to sea. Container ships near the horizon, slowly rotating turbines, the Maunsell forts. All is quiet. We’re on the lookout for the common scoters that have allegedly been seen bobbing off this coast.

We wander into the ruins of the Anglo Saxon church, scan the waters with telescope and binoculars. No luck so I turn my attention to the grass and scrub on the clifftops; a pied wagtail, a few linnets. I try the impassive sea once more. Nothing. The scoters have disappeared. So it goes.

I’ve been here so many times, charted the portrait benches and skylarks up on the meadowed cliffs. I’ll be back.

*

I have to hand it my old man; he knows his shit.

I have to hand it my old man; he knows his shit.

We reach a small wooden bridge straddling a murky green pool covered in fallen blossom, darting insects and other detritus. Table mushrooms jut out of one of the trees, like the handholds on climbing walls.

‘If we wait here for ten minutes or so we’ll see, I guarantee, a treecreeper.’

About eight minutes go by in which I swig water and smoke a cigarette. I listen to the warblers in the trees. We’ve heard nightingales, here, today.

Then a tell-tale flash of white, something moving like it’s a stop motion approximation of a bird, jerkily twitching up a nearby tree.

‘You see. A treecreeper’.

I grab the binoculars slung around my neck. The old skills are rusty but hard to lose and I find the bird through the lens in a few seconds. I’ve seen treecreepers before, and I know they’re common. So why am I here? For some people I’m aware the question would be: what is the point?

It boils down to specifics. We’re on the Stodmarsh RSPB reserve outside of Canterbury in the Kent countryside. I’ve been here many, many times over the course of my life. It’s not new. Like any place important to the individual, it ends up taking on a semi-mythologised status. There’s the real, living breathing Stodmarsh that I stand in now, and the Stodmarsh in my head, where all I ever saw or experienced here exists in one idealised afternoon, where am I simultaneously child, teenager and adult. There’s a Stodmarsh of the mind, my mind, and it’s a different place to where I stand. Inaccessible to all visitors but me.

‘I used to practically live here,’ my dad says. ‘Came here all the time and knew it inside out.’ It seems like he still does. He has the knowledge that only comes repetition and deep familiarity with a place. I envy him that.

The towns and the city, Canterbury, near here, can de depressing in their homogeneity. There’s something in knowing that here, in this exact spot by the murky pool, in this exact reserve in this part of a small country, on that exact tree, we will see a treecreeper. This is knowledge that cannot really be bought, brings no financial reward. Is, in a way, useless. And there’s the appeal. I can’t do this everywhere and I have to make the effort to be pointless.

‘A long time ago, I used to keep a little journal about the birds I’d seen and where I was, just notes about what the day was like, things like that.’

That, I think to myself, is a great idea.

‘You should have kept it up. I’d love to read them,’ I say.

We’ve set ourselves a challenge for the day, to observe 60 or more species in one day, driving around Kent from Reculver to Stodmarsh, from Stodmarsh to Oare, from there via Blean Woods if we have time and inclination.

Reculver was quiet and strangely dead; but here things are picking up. I’ve spotted blackcaps in the tree. Heard the beautiful song of nightingales, spinning the mind into a tangle of associations through poetry and music.

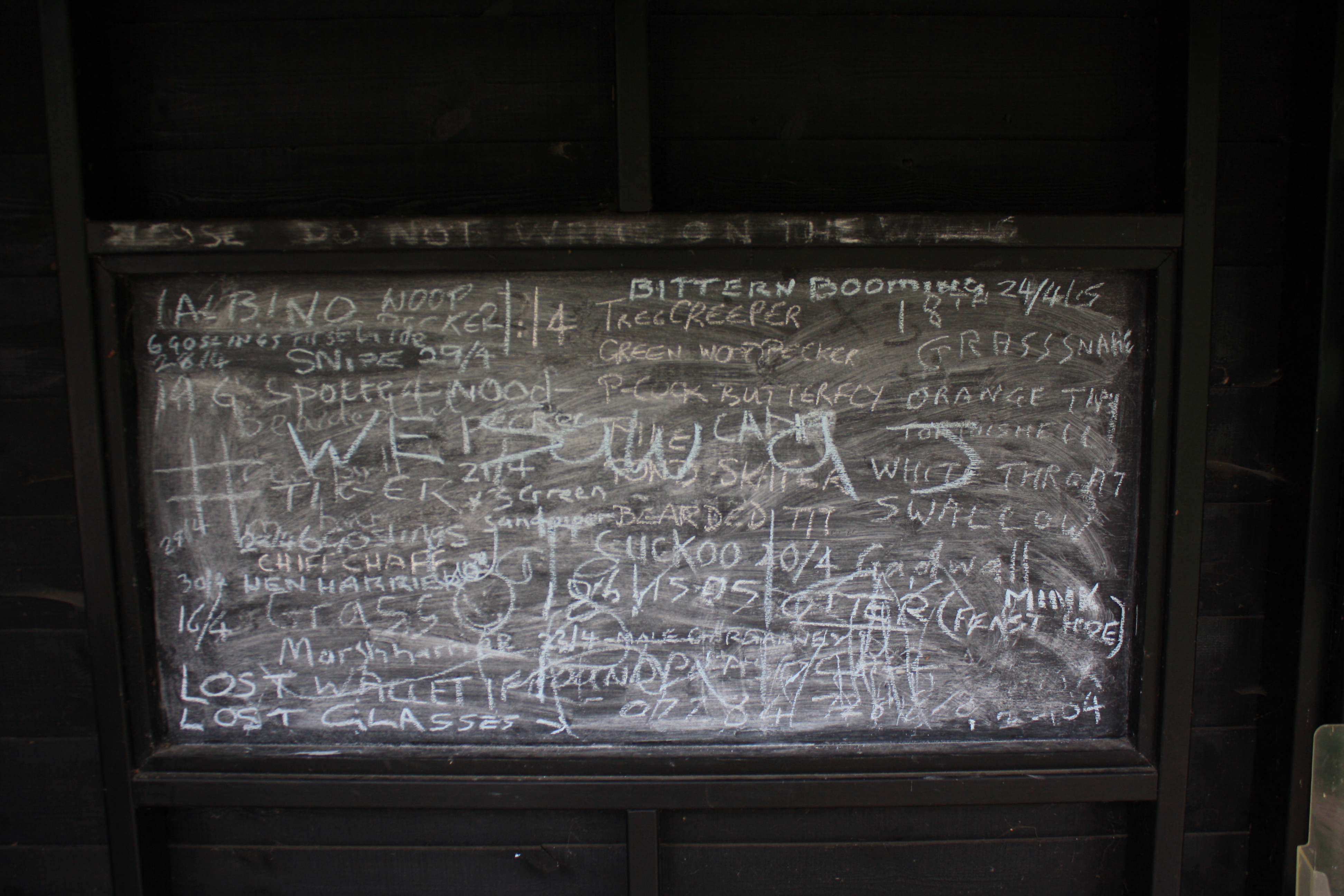

In the reeds and branches are grasshopper, reed, Chetti’s warblers. I get a perfect view of a whitethroat. Great crested grebes are resplendent out on the open water. I know somewhere here are bittern, though I’ve never seen one. On the chalk board information sign that greeted us in Stodmarsh carpark, where visitors can scrawl their sightings, was the odd poetry of BITTERN BOOMING.

In the reeds and branches are grasshopper, reed, Chetti’s warblers. I get a perfect view of a whitethroat. Great crested grebes are resplendent out on the open water. I know somewhere here are bittern, though I’ve never seen one. On the chalk board information sign that greeted us in Stodmarsh carpark, where visitors can scrawl their sightings, was the odd poetry of BITTERN BOOMING.

But the bird I really came to see, the reason I always return to these marshlands, is the marsh harrier.

I see a pair soon after we pull up. Their crazy and beautiful mating dance, like locked circus performers pirouetting down into the reeds. You can’t see them in many places, these majestic birds of prey. I have to come here. It’s a chance to spend some genuine time with family. It’s all about the specifics.

*

I was in Aberystwyth in west Wales with the novelist Niall Griffiths. We were drinking beer, sitting by the Irish Sea, talking about many things; landscape, punk rock, left wing politics, but something else came up, the subject of birds and bird watching. What it all means.

Red kites, those wonderful birds of prey, are plentiful in the skies in west Wales, as they are in many places. I’ve seen one in a dogfight with an angry carrion crow above the M4 near Slough, watched them float over suburban Buckinghamshire. When I was young, this was an impossibility. I remember tracking the last few native birds with my dad, deep into Wales, sometime in the 90s.

We agreed that having them back in numbers beats any thrill of seeing something rare. I am not a collector, a joyless list compiler.

Niall suggested something about the impulse to watch birds that hadn’t really occurred to me before, at least not on any conscious level. That, similar to ideas like the slow travel movement, here was something that could now be framed as a reaction to modern consumer culture. A way of stepping out of the loop, slowing down, reengaging with the complexity and diversity of the world. By doing something unprofitable, unfathomable to some, that required an engagement with specifics and not generalities.

It was an irresistible concept, reminding me of a quote from Kathleen Jamie in a Guardian interview from 2012:

When we step outside and look up, we’re not little cogs in the capitalist machine. It’s the simplest act of resistance and renewal.

Reading Jamie’s essay in her book Findings, ‘Peregrines, Ospreys, Cranes’ led me to reading the work of J.A. Baker. Helped me realise that all of this had some value to it, could be written about as literature. It meant something.

On the train to Aberystwyth, a long slow haul out from Birmingham International, I had watched England fall away and become, almost imperceptibly, somewhere else. To help pass the time I pulled out my notebook and jotted down any of the birds I could see out of the window. Just writing the words down on paper and looking at what was there, at that moment, was a therapy.

Little egrets out on marshy ground, buzzards soaring high, reptilian grey herons, curlew and waders too far off to identify. Pulling into Aberystwyth, I saw a red kite floating above gorse and grass.

*

The thing is, my dad was a collector of sorts; something shameful in fact. Dipped his hand into the nests of kestrels as a young boy in the 1960s. A small egg collection. Illegal even then (the practise outlawed in 1954) and contemptible now, though it still continues. At least, he says, it taught me a lot of what I know about birds. A horrible irony, but in the end it probably did some good right? Without those experiences, of the precarious branch-balanced theft of raptor eggs, I may not be writing this now.

The thing is, my dad was a collector of sorts; something shameful in fact. Dipped his hand into the nests of kestrels as a young boy in the 1960s. A small egg collection. Illegal even then (the practise outlawed in 1954) and contemptible now, though it still continues. At least, he says, it taught me a lot of what I know about birds. A horrible irony, but in the end it probably did some good right? Without those experiences, of the precarious branch-balanced theft of raptor eggs, I may not be writing this now.

My dad was just a kid, collecting, for reasons he would have found hard to articulate, then. Some human beings, however, will always attempt to monetise the world. These days, as to be expected, the highest prices go for the eggs of the rarest birds. It’s highly illegal but the stakes are high. They, the hunters, most likely know the birds and their environment, better than I do. They still make me sick.

I am not a collector. If we can even apply human terms to the experience of watching the birds, what is most important is that it is free. The attempt to list, categorise, possess can be poisonous. But we all have the impulse to some extent; I’m trying to hit 60 species today, after all.

*

For an enthusiasm so easy to mock, birds have the ability to elicit extremely powerful emotions and responses in human beings. Vivid in myth and music, in poetry and literature. Maybe there’s something in the idea that the painter, the writer, the musician has a keener eye for the world; though I personally think the urge to get outside, trudging through mud and marsh, to find the birds that you cannot find a mile down the road, is universal. Perhaps writers just have better tools with which to transmit the feelings that birds can instil.

For an enthusiasm so easy to mock, birds have the ability to elicit extremely powerful emotions and responses in human beings. Vivid in myth and music, in poetry and literature. Maybe there’s something in the idea that the painter, the writer, the musician has a keener eye for the world; though I personally think the urge to get outside, trudging through mud and marsh, to find the birds that you cannot find a mile down the road, is universal. Perhaps writers just have better tools with which to transmit the feelings that birds can instil.

Once forgotten, now oft-quoted and (rightly) lauded is the astonishing work The Peregrine by J.A. Baker. When I was discovering, then actively hunting, for literature of this sort, these lines of Baker’s, from the beginning of the book, captured perfectly the feelings I have about a bird like the marsh harrier and a place like Stodmarsh:

Before it is too late, I have tried to recapture the extraordinary beauty of this bird and to convey the wonder of the land he lived in, a land to me as profuse and glorious as Africa. It is a dying world, like Mars, but glowing still.

Part of the point, and the appeal, is that language always fails. Whatever I, or anyone else, writes can only ever be an approximation of what I actually see, what is felt in those split-second moments when something happens. When the harriers spin down into the reeds, when the peregrine breaks cover, when whatever bird most captivates you does what it does. If language could capture what we exactly mean, I wouldn’t write this, and come back to the subject time and again, and books about birds would not continue to be written.

Reading the novels of Niall Griffiths, where nature is gory-red in tooth and claw, helped me realise that the realm of birds could be transmuted into ecstatic, epic visionary literature. Consider this depiction of a shrike in the novel Sheepshagger, the notorious prey-impaling ‘butcher bird’:

…his nightmares stoked for years to come he is scolded by some branch-perched bird with hoarse and hiccupping smacking sounds, the white underparts unbarred, head and nape the colour of ashes, a certain ferocity to the curve of its beak, this shrike like some thrush or jay gone demented, psychotic, a songbird whose tune is the screaming of souls.

Birds inspire fierce, extreme reactions; reactions that whether inspiring or horrific, can make a person feel alive.

*

In the car, once again as predicted, a burst of brilliant yellow shoots from a roadside verge. A yellowhammer, shooting over the farmland.

Our third port of call for the day is the Oare Marshes near Faversham. Another reserve, managed by Kent Wildlife Trust, flat and with the touch of the post-apocalypse to it. Boats rusted and looking unloved float on the waters. Pylon legions stretch into the sky as swifts and swallows, back for the summer, swoop and dart among the wires, catching insects. The first I have seen this year.

Here waders are in heavy numbers and I try to photograph a flock of bar-tailed godwits landing on a tiny island. Redshank fly by. Gadwall, pintail and tufted duck sit on a sandbank. But more striking than anything are the avocets, feeding on the mudflats; a bird I haven’t seen in the flesh for many years, mascot of the RSPB itself, symbolic of the bird protection movement. Striking black and white, bill like a curlew reversed, a bird made extinct in the 19th century, brought back just after World War Two. Icon of all that this means.

Things like this make it all worth it, and the joy of just looking, being where I am in this specific place at this time of year, watching a bird that represents a little bit of hope, and spending what they used to call ‘quality time’ with my father. It is a way to combat the forces of stifling blandness seeping into contemporary British life; the simplest act of resistance and renewal.

We smash our arbitrary target. One of the last birds we hear, but do not see, is a skylark. According to my dad, identification, whether visual or aural, is enough to put it on the list. I’ll go with his judgement, and it’s ok, I’ve seen them before fluttering above the wild grasses of Reculver cliffs.

‘Tis love of earth that he instils,’ goes a line in the famous poem, ‘The Lark Ascending’, by George Meredith.

At its essence, birdwatching is as simple as that.

Gary Budden is co-founder of independent publisher Influx Press and assistant fiction editor at Ambit magazine. He lives in London. Click here to read his blog: New Lexicons.

[…] For more birdwatching from Gary, check out Specifics: Thoughts on birds and birdwatching […]