WORDS: Ben Thompson

The 13th Century church of St Leonard’s occupies the kind of hillside position – looking down over the stranded Cinque Port of Hythe and then out across the English channel – which is traditionally described as ‘commanding’. And yet the most eye-catching of the many intriguing artifacts inside this splendid building is also the meekest; a welcome note pinned up in the porch which testifies to a brand of Anglicanism so inclusive (“You are welcome whatever your beliefs, lifestyle or sexuality… even if you find organised religion irrelevant”) that in times not long past it would scarcely have qualified as Christianity.The extent to which the humble mood of this greeting has been dictated by the church’s custodianship of Britain’s largest collection of human skulls can only be guessed at.

For health and safety reasons, the crypt (which is technically an ‘ambulatory’ rather than a crypt, but let’s not split hairs) can only be approached by leaving the church grounds and walking round the Eastern end of the building. Once inside, this unexpectedly airy and congenial space confounds sepulchral expectations. It’s more like a good sized wine-cellar than the spectacular bone-yard of the Capuchin friars in Rome, with the comfortable domesticity of the setting offering a pleasing counterpoint to the industrial-scale evidence of man’s mortality displayed therein.

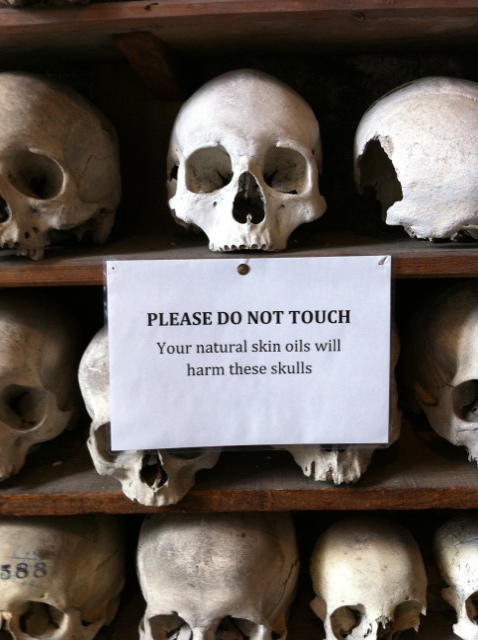

Neatly shelved behind chicken wire at either end of the crypt – as if to preclude an improbable escape attempt – are racks of human skulls,1022 in total, accompanied by carefully-worded notices advising visitors on the proper way to behave towards them. In the middle of the room a somewhat motley array of other relics (badly set broken bones, bits of the stained glass window destroyed by a WWII bomb) rest against one wall, while against the other lies a huge stack – roughly 5 feet square and 25 feet long – of carefully assembled bones and skulls, atop a wooden base. It’s not hard to see why this veritable human lasagne took several attempts to get right on its original construction in 1910.

In the course of two separate visits to St Leonard’s in the late summer of 2014, I was struck by the way the personalities of the different guides impacted on the atmosphere. Both pointed out particular treasures such as the skull in which a bird had made its nest, and gave roughly consistent account of the various conflicting theories as to the provenance of the exhibit (Battle? Not enough of the right kind of injuries. Plague? The evidence suggests not. Reorganisation of churchyard? Disappointing, but probable).

In the course of two separate visits to St Leonard’s in the late summer of 2014, I was struck by the way the personalities of the different guides impacted on the atmosphere. Both pointed out particular treasures such as the skull in which a bird had made its nest, and gave roughly consistent account of the various conflicting theories as to the provenance of the exhibit (Battle? Not enough of the right kind of injuries. Plague? The evidence suggests not. Reorganisation of churchyard? Disappointing, but probable).

But whereas the first, male custodian, perhaps in his late 60s, made it his business to leaven the seriousness of the atmosphere with jokily ghoulish announcements (“Are you here to see the bones?”) before returning to his reading (a book about necromancy); his female colleague of a similar age intensified the sombre mood by picking out the particular cranial bumps which suggested their erstwhile owner-occupants had suffered from cancer.

The souvenir shelf on the way out – postcards, pencils, key-rings, big badges, leather bookmarks, all inscribed with the striking St Leonard’s Crypt large skull motif – is Mexico’s Day of the Dead as re-imagined by Martin Parr.

The souvenir shelf on the way out – postcards, pencils, key-rings, big badges, leather bookmarks, all inscribed with the striking St Leonard’s Crypt large skull motif – is Mexico’s Day of the Dead as re-imagined by Martin Parr.

This is a parallel version of Britishness in which the certainty of death is something to be embraced from the off, rather than kept at arm’s length like an annoying relative at a wedding (you know you can’t escape them in the long run). Although one American tourist pronounces it “creepy”, the overall effect – to my mind at least – is strangely serene. The only genuinely ghoulish note is sounded by the decor choice of a neighbouring residence (by it’s position probably the former vicarage) which has picked up the morbid theme with a patio made out of smashed up old headstones – or, to use the technical term, ‘crazy graving’.

St Leonard’s crypt is currently – like so many of Britain’s finest tourist attractions – closed for the winter, but reopens on May 1st. Visit their website here.

Ben Thompson (aka @btfoshizzle) is a critic and ghostwriter whose must recent publication is Ray Winstone’s Young Winstone (Canongate, £20) – a memoir of cockney indiscretions with an undertow of Sebaldian drift.

He also presents The London Ear radio show via www.resonancefm.com on Thursdays at 3pm