WORDS & PICTURES: Gareth E. Rees

This is an edited Transcript of the talk I gave at the Hastings Storytelling Festival, Wednesday 9th November 2016.

I want to tell you a story.

It’s about how an erotic encounter with an electricity pylon on Hackney Marsh led to me having a religious vision in the car park of a Morrisons in Hastings seven years later.

I’m calling this talk Uncanny Landscapes, but not because it’s all about ghosts.

I mean uncanny in its definition as ‘strange or mysterious, in an unsettling way’. I also take inspiration from Sigmund Freud, who saw the uncanny as being what unconsciously reminds us of our forbidden, repressed impulses, particularly in places or situations that make us feel uncertain.

It is my belief that all landscapes are uncanny, when you look deep enough, when you let them get under your skin, when you challenge the illusion of objective reality, when you allow your fears and urges to run riot…. when you open your imagination.

You’ll see there’s mystery and strangeness in even the most mundane things, whether it’s an Asda car park, concrete wall, park bench or a cigarette-strewn verge.

In everything there is a story.

So my particular story starts back in 2008…

I’d recently got married and moved into a flat in Clapton. My wife was pregnant. I had crippling backache from too much sitting at a computer, and thought that a pet dog might get me out and about.

In May I bought a cocker spaniel named Hendrix and started to take him for walks to bottom of Millfields park, which ended at a river. On the other side of which was a concrete peninsula, broken down, scrappy, populated by ducks. Beyond was a skyline where pylons dominated, not buildings.

Here’s a piece from my book marshland that describes it.

“Now my dog had brought me to a threshold between the city I knew and a strange semi-rural wetland known as ‘the marshes’. On one side of the river, London was in hyper flux, perpetually regenerating, plots as small as toilets snapped up by developers, gardens sold off, Victorian schools turned into apartments, bomb sites into playgrounds, docklands into micro-cities, power stations into art galleries. Everything was up for grabs.

On the other side of the river – a stone’s throw away – lay a landscape of ancient grazing meadows scarred with World War II trenches, deep with Blitz rubble, ringed by waterlogged ditches, grazed by longhorned cows, where herons and kestrels hunted among railways, aqueducts and abandoned Victorian filter beds. It was untamed, unchanged in some parts since Neolithic times. It had not yet been claimed by developers. It was nobody’s manor.

On the other side of the river – a stone’s throw away – lay a landscape of ancient grazing meadows scarred with World War II trenches, deep with Blitz rubble, ringed by waterlogged ditches, grazed by longhorned cows, where herons and kestrels hunted among railways, aqueducts and abandoned Victorian filter beds. It was untamed, unchanged in some parts since Neolithic times. It had not yet been claimed by developers. It was nobody’s manor.

Discovering this place was like opening my back door to find a volcanic crater in the garden, blasting my face with lava heat, tipping reality topsy-turvy.”

[Marshland, Influx Press, 2013]

This was the beginning of a new chapter in my life. I walked the dog every day, further and deeper into the landscape, among Jurassic-sized hogweed and looming pylons.

It felt as though I was time travelling. History was strewn in fragments across the marsh. Overgrown, buried or re-purposed. I could stand on a dead Victorian aqueduct, watch cows grazing on medieval pasture land scarred with bomb craters, and see the gherkin and Shard skyscrapers on the skyline.

A classic example of this is Coppermill field, which you reach by ducking under a 5ft bridge, like you’re Alice in Wonderland.

“I staggered from the bridge to face a dizzying panoply of features; winding country road; car park; railway siding with concrete sleepers; pylon; wedge of meadow; water tanks; the tower of a copper mill and gleaming oxygen cylinders. Fragments from a dream.

“I staggered from the bridge to face a dizzying panoply of features; winding country road; car park; railway siding with concrete sleepers; pylon; wedge of meadow; water tanks; the tower of a copper mill and gleaming oxygen cylinders. Fragments from a dream.

Stuck out in the scrub by the reservoir fence was the giant banquet table they’d erected the year previously. I’d never seen anyone eating at this table.I’m not surprised. For me, eating here directly beneath the pylon cables would be like licking soup off a nuclear missile.

I sat on the chair at the head of the table, my legs dangling. In the bridge I’d been gigantic. Now I felt miniaturised. The pylon behind me was poised to stride over my head, lashing the sky with black cable. A passing freight train hooted ‘Whooooooooo’. Distorted `80s pop music seeped from a parked car. From the trees near the train track I could hear the laughter of kids blending with the banter of railway workmen until it sounded like they were all playing some sinister game together behind the weeping willow’s shroud. I remembered how I used to spend endless afternoons in trees like those, private dens with leafy curtains in which we were free to dream up visions of secret spy rings, space stations and war bunkers.

Suddenly I understood what it was I loved about the marshland. Even though I had not grown up here, I’d known this place all my life. Squeezing into its thickets, stooping beneath its bridges, thrilling at the roar of trains, my childhood imagination had been released after decades of repression.

No other landscape – no park, mountain, lake or coastline I have visited anywhere in the world – has such power to evoke that lost world of youth, when there was magic and terror to be found in the hedgerows, reservoirs and scrapheaps at the edge of town.”

[Marshland, Influx Press, 2013]

In particular I became obsessed with a pylon.

In particular I became obsessed with a pylon.

There was a whole line of them marching down the Lea valley, but this one was different… it stood apart from the others, in the walled Victorian filtration plant – like an invader from an HG Wells novel. You could see its reflection shimmer in a pond. Every day I’d stare up and take photos of it. To me the little rings of barb wire looked like S&M garters. There was a feminine quality to the shape, as well as the obvious phallic one.

This inspired me to wrote the short story ‘A Dream Life of Hackney Marshes’. It was about a man who had a breakdown after his daughter’s birth, becomes addicted to his dog’s cataract eye drops, which give him a unique blurry fuzzy view of reality, and begins an affair with this very pylon, who he names Angel.

“Sometimes I’d sit on the bench next to Angel and feel her hum, while my dog would chase his shadow, or sleep in the shade. When he was settled I’d dab cataract medicine into each eye, wait for my pupils to crank open, the irises to fire up, then out with the iPod.

I’d started recording a series of electronic mixtapes. Drone. Minimalist techno. Really it wasn’t my taste. It was hers. I was only interpreting the vibrations. Giving her what she wanted. She loved the glitch sound. Our favourite track was ‘Test Pattern #1111’ by Ryoji Ikeda, a Japanese sound artist.

Together we’d sing it: “Chk chk chk chck chck – tsssssssssssssssssssssst – tk tkt tk tk tkt kk –tssssssssssssssssssss – tk tk tkt tk.”

Afterwards I’d go between her legs and point my camera upwards, let the sun fragment in her girders, spatter rays across my lens. Gently she’d tickle the nape of my neck with volts. It was wonderful.

“Chk chk chk – tsssssssssssssssssssssst.” I would coo. “Tk tk tk tk.”

A quick cigarette and I was off round the filter beds, taking pictures from every angle, let her slip in and out of view, play peek-a-boo behind the bushes.”

[Acquired for Development By…. Influx Press, 2012]

The story was really about my affair with place. The pylon represented a skewed, subjective, creative vision of landscapes that are often dismissed as ugly, or representing the worst of progress.

My new obsession was selfish and sordid – but I was now writing decent stuff for the first time in my life.

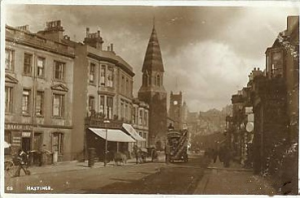

As the writing of Marshland intensified, I did less and less copywriting work. We were struggling with debt and couldn’t afford living in London. So we moved to a dilapidated Victorian house in Hastings where continued the walking I’d been doing on the marshes, but in an entirely new landscape.

But something about moving to the coast triggered flashbacks to the two other places I’ve lived on the coast…

Dover where I went to school…. and St Andrews University in Scotland where I studied a postgraduate year in 1996. That academic year would end with the tragic death of my best friend Mike who fell from the castle after we spent the day drinking together.

Here’s what happened on my first walk…

“Hastings pier was a charred skeleton. The remains of a campaign banner, flapping from the rusted gantry, bore the word SAVE. Steps led me down to the beach. It was low tide.

“Hastings pier was a charred skeleton. The remains of a campaign banner, flapping from the rusted gantry, bore the word SAVE. Steps led me down to the beach. It was low tide.

The shingle gave way to a slab of sand, shimmering like meat, peppered with shells. The air shifted and warped. Heat, possibly, rising from the earth, or something else. Mesmerised, I lost all sense of the town behind me. There was only sand, sea, rocks, sky. A gust of salt air whipped into my nostrils. It carried a memory. Or not even a memory, but the very sensation of a moment long forgotten, as if the past 20 years had never happened and I’d crossed a time-space dimension to the West Sands of St Andrews, on the coast of Fife, nine hundred miles north, 1996. It was the beach where they filmed Chariots of Fire, a long curving paleness against the wide muddy blue of the North Sea, stretching towards the cathedral and castle beyond. My best friend Mike was a little ahead, in jogging bottoms and a t-shirt, despite the chill, turning back to me and laughing. “Come on,” he said, “You fat bastard.”

He’d challenged me to a run that morning, teasing me about my nascent beer belly. In my years at Sheffield University I’d done little more than booze and read. By the time I came up to St Andrews to study for a Masters, Mike was in training for the army. They made him do things like haul a backpack of rocks up a Munro without any sleep while being attacked by ninjas, or so he told me anyway. He could be full of shit like that. But I couldn’t deny the evidence on the beach as he accelerated away from me with surprising speed. Faster. Stronger. Unstoppable.

Lungs heaving, I crumpled onto the sand and watched him run towards his destiny.

That castle, looming.

There was a castle in Dover, where Mike and I first met at school in 1985 and later became best friends. We’d pass it on the way into town to go underage drinking on Saturday evenings, wearing ridiculous sports jackets we’d plundered from charity shops to make us look older. There was a castle in St Andrews too, from which Mike would fall. And there was one here in Hastings, though it was little more than a few crooked teeth on the jaw of West Hill. On the vertiginous rocks beneath the ruin, teenagers huddled in folds of sandstone and looked toward France. Like Mike, they liked to climb, to live on the edge. Kids these days, same as kids those days.”

In Hastings I was getting weird memory triggers but I also noticed that the whole town was a memoryscape. A place where people come to create memories on holiday, but also to commemorate the dead. All along the promenade and in the parks, on West and East Hill, were memorial benches. They became my new obsession. I started reading them, photographing them, imagining the lives and deaths behind them.

Here’s a piece from a chapter I wrote for an anthology called Walking Inside Out: Contemporary British Psychogeography. This is me on West Hill walking the lines of benches reading the inscriptions.

Here’s a piece from a chapter I wrote for an anthology called Walking Inside Out: Contemporary British Psychogeography. This is me on West Hill walking the lines of benches reading the inscriptions.

“There’s something odd about the benches. Rather than located in paces where someone might stand to appreciate a view of the sea, they are aligned according to the trajectory of footpaths which cut across the park in diagonals. They don’t signify an actual moment space-time as experienced by the deceased. They’re a utility for rest. A public narrative to be read as people walk by on their way to other places of local interest – the castle, West Hill Café and historical town.

If their true purpose was to signify moments in a life, they would be placed in those invisible loci where dog walkers, lovers and loners leave the path to weave across the grass, gaze out to sea, clamber over the rocks and talk – kiss – declare their love –end the relationship – reveal the secret!

Memories are made in those moments of transgression.”

[Walking Inside Out: Contemporary British Psychogeography, Rowman & Littlefield, 2015]

In the chapter I contrast the West Hill with the East Hill, which takes a slightly different tone.

“On a crankily humid day I slip through an alley beside the Dolphin pub and climb the steep steps alongside the Victorian railway lift that takes tourists to the top of East Hill. There are memorial benches towards the summit. The epitaphs are different in tone to those on West Hill, looser and wittier, with hints at an authorial voice – or even the voice of the deceased themselves, humming in the depths of their wooden chambers.

“On a crankily humid day I slip through an alley beside the Dolphin pub and climb the steep steps alongside the Victorian railway lift that takes tourists to the top of East Hill. There are memorial benches towards the summit. The epitaphs are different in tone to those on West Hill, looser and wittier, with hints at an authorial voice – or even the voice of the deceased themselves, humming in the depths of their wooden chambers.

Jim & Trixie Butchers: A Wonderful Hastings couple

OLLY ‘9 TOES’ CAREY

Michele Campling: I don’t know where I’m going from here but I promise it won’t be boring

Never a Dull Moment – In Loving Memory of Gary Batcheler

At the very top, by the exit of the funicular lift there is a single bench beneath a tourist information board that says:

Mad John?

Who on earth were you, Mad John?

I sit down by his name. His bench is positioned so that it takes in the whole Hastings vista – the Stade, the promenade, the pier, and the curvaceous rump of West Hill rising from the old town. Unlike the infrastructural location of many benches on that rival elevation, this seems the most natural spot someone would stand to soak it all in.

I can imagine John’s gaze as if it were my own. I smirk on his behalf at the stuffy formality of those memorial benches on West Hill, some of whom he knew when they were more than just names on wood. There’s Mrs Jenson who was ‘much beloved’ – oh yes, beloved alright, she was known as the town bike back in the ‘50s. Everyone had a go. Then there’s Dicky Pierce, god knows why he’s up on that hill. The lazy fat sod barely left his bar stool at the Stag. Harry and Jill Michaels, ‘a loving couple’, god you should have heard Harry going on about her behind her back.

Yet there they all are, laughs Mad John, dead and turned to benches instead of dust, arranged in rows, seething at each other for taking the superior spots. Oh, how they’d love to wrench their little wooden legs from the earth, grow big eyestalks, and go clattering across the hill like crabs to find a viewpoint away from those tourists and their big sweaty arses. Ah for shame, West Hill. It’s here on East Hill where the benches are arrayed with naturalism, wild and random, with the most majestic views. East Hill is where the chaos happens.”

[Walking Inside Out: Contemporary British Psychogeography, Rowman & Littlefield, 2015]

It’s not just memorial benches that tell a story in Hastings. There are more stories written into the fabric of the place, but you have to look closer.

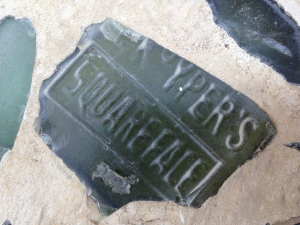

Bottle Alley for instance, leading from Warrior Square Garden to the Pier – a double-decker promenade built in the 1930s by Sydney Little.

Bottle Alley for instance, leading from Warrior Square Garden to the Pier – a double-decker promenade built in the 1930s by Sydney Little.

The back wall of the lower deck is a fusion of concrete and broken bottles which Little discovered in a rubbish tip, then separated into emeralds, oranges, greens and crimsons.

One day I walked along the alley, staring intently at each section, characterised by different colour mixes and pattern formations. Some seemed a chaos of smashed glass until I looked closer and forms emerged, like in a magic eye picture.

I could make out the bottoms of wine bottles with markings of the manufacturers visible. Running my fingertips over them, the glass was no longer an abstract fragment, but a bottle touched by real hands that brought succour to beating hearts.

I could smell tannin and hear the hullaballoo of drinkers as they laughed, argued and spilled their secrets. The last piss-up before being shipped out to the Great War. A homecoming banquet soured by absences, the glass beaded with tears for the dead. Then good time drinking. The raucous dance parties of the post-war prosperity jazz years, followed by the fearful, consolatory boozing of the General Strike. The smashed dreams of the 1929 crash. The remnants of the spoiled party flung onto the rubbish heap for Sydney Little to find.

I could smell tannin and hear the hullaballoo of drinkers as they laughed, argued and spilled their secrets. The last piss-up before being shipped out to the Great War. A homecoming banquet soured by absences, the glass beaded with tears for the dead. Then good time drinking. The raucous dance parties of the post-war prosperity jazz years, followed by the fearful, consolatory boozing of the General Strike. The smashed dreams of the 1929 crash. The remnants of the spoiled party flung onto the rubbish heap for Sydney Little to find.

All of this was encoded into the promenade’s structure, much like the names carved into park benches or the sandstone of West Hill.

In Hastings, memory is a raw material.

I love the mixture of the human and the natural on this part of the south coast. For instance, the way the outflow pipe juts from the beach in the same spot where a U-Boat used to lie.

On tow from France to Scapa Flow in May 1919, U-118 broke loose and rolled toward the Sussex shoreline. French gunships gave chase, trying to break it up with heavy shelling, but as the submarine moved closer to Hastings, they were forced to stop and turn back. It settled on the beach in front of the Queen’s Hotel. It was a tourist attraction for the summer but they dismantled it in October. Most of it went for scrap. Other pieces were snatched as mementos and dispersed across the country, while some of the keel was left under the beach

The buckled outflow pipe looks like a remnant of that old U-Boat’s torpedo tube trying to crawl out from under the shingle and return to sea.

To me this pipe a confluence of local narratives…

The lime green water that gushes from it comes down through Alexander park from Roar Gill, a ravine you can walk to from my house, cut into sandstone by water which once poured from a great waterfall known as Old Roar, a Victorian tourist attraction. This has since dried up, but for a stream coming from a grotto called Little Roar gill, which feeds into Alexandra park and trickles down to the sea.

Water has always flowed down this valley, feeding the natural harbour that used to exist when Hastings was a Cinque Port…. before climate change storms in the 13th century ravaged the coastline, collapsing half the castle into the old harbour and silting it up, creating the America Ground where the shops are today, and beneath which water still fizzes, carrying traces of the deep past.

But I can go back even further…

In the cretaceous times this area was river network from which Iguanodons would drink, their bodies later hewed out of the rock in Silver Hill near Old Roar Gill by Charles Dawson, the local amateur archaeologist and palaeontologist who would later concoct the infamous Piltdown man scam, claiming to find the missing link in a gravel pit.

So when I see that outflow pipe I see the WWI submarine, Charles Dawson, the Victorian tourist boom, climate change of the 14th century and the cretaceous age, all in one.

Another thing that baffled me when I moved here was, why is there a church in the seam of rock above the old town?

These are the Black Arches, carved by a man named John Coussens in the 18th Century.

But what was Coussens trying to say with these? Mischief? Art? Graffiti? A drunken bet? Divine inspiration? Perhaps he saw God in the hills. Perhaps he wanted to open up the doors to another realm. Perhaps he just want to write himself into the landscape, into history.

Coussens is also said to be responsible for the Minnis Rock, a 6ft high seam of sandstone rising from mud like the upper half of a human skull.

There are three carved entrances to the cave, like the Black Arches, but they lead into three physical chambers, with holes carved in the partition walls. The surface of the Minnis rock was grooved with human markings, including a carefully scribed date: 1727.

There are three carved entrances to the cave, like the Black Arches, but they lead into three physical chambers, with holes carved in the partition walls. The surface of the Minnis rock was grooved with human markings, including a carefully scribed date: 1727.

In 1892, a historian named Byng Gattie claimed the Minnis Rock had been carved out as a chapel for local sea farers to pray in.

This infuriated the local archaeologist, Charles Dawson. In a newspaper article he retorted that a sorely mistaken Mr Gattie had discovered a modern antique, carved by Mr John Coussens at the end of the previous century.

The irony is, at the time he was scribing this rebuke, Charles Dawson was embarking upon his campaign of archaeological manipulations. These included exploring the Lavant Caves in West Sussex and sneaking in prehistoric artefacts… faking a toad in flint… faking a roman cast iron statue… faking the fossil of a cretaceous mammal… a path that would eventually lead to him faking the discovery of the missing link, the Piltdown man, which would be the world’s greatest archaeological scams.

So when it came to the Minnis rock, there was no doubt he was miffed that he hadn’t first had the idea to excavate these caves. With his unique fictionalisation skills undoubtedly he would have found something to make them significant, whether there was anything there or not.

So when it came to the Minnis rock, there was no doubt he was miffed that he hadn’t first had the idea to excavate these caves. With his unique fictionalisation skills undoubtedly he would have found something to make them significant, whether there was anything there or not.

There’s a link between Charles Dawson and the final part of my story.

Because it was in Hastings, thanks to Charles Dawson, that I’ve become obsessed with car parks. The spaces around and between chain stores – ASDA, Morrisons, McDonalds, B&Q.

It began when I decided to take a walk around the ASDA car park in Silverhill. I’d been in a lot of car parks, walking between the car and supermarket, as you do… but I’d never treated it as a destination.

I expected that supermarket car parks were non-places, boring corporate blots on the landscape.

But instead what I found in Silverhill were dinosaur prints, not real ones, but painted into the concrete around the shopping trolleys. A colourful dinosaur mosaic design by school kids. Big prehistoric looking stones among the foliage.

But instead what I found in Silverhill were dinosaur prints, not real ones, but painted into the concrete around the shopping trolleys. A colourful dinosaur mosaic design by school kids. Big prehistoric looking stones among the foliage.

Crass and cartoonish maybe, but at least it was an attempt to embrace the historical context.

In the late 18th and 19th centuries, when Hastings was a national hotspot for Victorian tourists, and they were building St Leonards, much of the stone for the town was quarried locally, and Silverhill was one of those places.

As they hacked into the stone, people discovered strange monsters. Iguanodons, to be exact. One in the 1870s and another in the 1890s. The latter find was extracted and shipped to the British museum by Charles Dawson, who cheekily pocketed the cash.

So it turns out ASDA’s car park was pretty interesting. And so is my local Morrisons.

This is an extract from my website, Unofficial Britain.

“Morrisons is at the bottom of my road, via an arched pedestrian underpass. It feels strange to walk here without any intention of going into the supermarket, as I am doing now at 7pm on a Tuesday…

The last remaining cars glisten in the first glow of artificial light. The lampposts are topped with needles, to deter or impale herring gulls. The white road markings are faded, more suggestion than law. The ‘mother and child parking’ avatars have exploded heads.

The last remaining cars glisten in the first glow of artificial light. The lampposts are topped with needles, to deter or impale herring gulls. The white road markings are faded, more suggestion than law. The ‘mother and child parking’ avatars have exploded heads.

Three lanky men in their early twenties smoke by the car park’s entrance, talking in low voices. They stare at some teenage skateboarders gathered by a wall beneath a NO SKATEBOARDING sign. More skaters approach, weaving through parked cars, clattering and Tarzan-yelling.

I cut the recycling bins. A woman sat in her car seems nervous as I approach. She starts fumbling with her keys. Once I’ve passed, I glance back. She’s got her head turned round, staring at me, wide-eyed. She fires the engine and putters away. I catch the whites of her eyes once more as she accelerates down the exit road.

The recycling station is deserted. Behind is a maze of hedgerows. Half a bed frame has been tossed into the greenery. I follow the verge around to a wall where there’s a crashed Mercedes with a crumpled bonnet and – bizarrely – a number plate that says 1066.

I get the sense I’ve stumbled into the aftermath of a drama played out between the woman in the car, the lingering men, the skateboarders and the missing Mercedes driver.

I get the sense I’ve stumbled into the aftermath of a drama played out between the woman in the car, the lingering men, the skateboarders and the missing Mercedes driver.

There are secret lives and deaths that happen right in front of our noses. We just can’t see them.

I think about Father Joseph Williams, a priest who died at the wheel of his car in Morrisons’ car park in Bedfordshire in 2013. It was three days before police discovered him. Or there was the burning body found in a Sainsbury’s car park in Chippenham in 2012. Or the businessman who went missing in an Asda car park in West Yorkshire on Valentine’s day in 2007, never to be seen again.

The supermarket car park is a place where you can lie dead for days and nobody will notice. This is because when you drive in and out of a car park. the space outside your car is largely invisible. You notice only your parking bay, the trolley drop-off point, and the quickest route in and out of the store, via the designated zebra crossings.

The rest may be a bubbling lake of fire for all you care. You don’t notice the rest. You don’t go there.”

When I experienced a supermarket car park with as much fascination as the marshland, I began to question something I’d long taken as a truth – that car parks are non-places, identikit zones without geography, nature, social history or cultural nuance.

During the Victorian time, this Morrisons car park was fundamental to the town as the site the Hastings & St Leonard’s Gas Company, receiving coal that landed on the shore from the north of England and using it to bring light and heat to the big new houses of the town.

During the Victorian time, this Morrisons car park was fundamental to the town as the site the Hastings & St Leonard’s Gas Company, receiving coal that landed on the shore from the north of England and using it to bring light and heat to the big new houses of the town.

As the population rose and gas consumption soared, the site became too small. In order to avoid a £4,000 coal due levy from the local council, the gas company’s shareholders voted to move the works from Hastings to Bexhill in 1907.

However the gas offices remained for decades with a central tower that jostled for supremacy with the neo-gothic steeple of St Andrews Church next door, on the site of the Morrison’s petrol station.

The interior of the church was decorated by local tradesman Robert Tressell, who would write a book called The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists which described the plight of exploited working class people in a fiction version of Hastings called Mugsborough. He lived in a property at the top of some nearby steps up the West Hill and describes in the book the shady dealings of the Gas and Electronical company moguls and shareholders who moved the works away from Queens road to line their own pockets.

So for me this car park is the overlooked epicentre of Hastings’ radical history.

So for me this car park is the overlooked epicentre of Hastings’ radical history.

The church was demolished in 1970, and the whole site was levelled in the 1980s to become a supermarket, while the Church was replaced with its affiliated petrol station. But remnants remain. The road into the store is still called Waterworks Road. There’s a yard of workshops that now house blacksmiths, dog groomers and car washers.

Sometimes when I walk on the highest road of West Hill and look down into the valley at the Morrisons, I see the ghostly outline of that history, the roofs of the amassed vehicles glistening in the sun like water on the surface of the ancient river to the vanished harbour, the clock on the conical watchtower counting the hours til hometime for the ghost workers of the Gas Works.

I see the people eagerly filing into the store through the Petrol Station like worshippers at St Andrews Church on a Victorian Sunday. This place of spiritual power and energy supply has retained its influence, now the hub of the new religions of oil and commercialism.

A supermarket car park can tell a complex story when you take time to think about it.

This is a line of thought all began for me with a pylon on hackney marsh. The idea that you can transform the world with imagination, but not to escape reality, but to see it from many sides and points of view, to try and find some kind of truth, to bring the magic and mystery back to the places where we live.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gareth E. Rees is author of Marshland: Dreams & Nightmares on the Edge of London. His work appears in Mount London: Ascents In the Vertical City, Acquired for Development By: A Hackney Anthology, An Unreliable Guide to London, Walking Inside Out: Contemporary British Psychogeography and the album A Dream Life of Hackney Marshes.