WORDS: Gareth E. Rees

WORDS: Gareth E. Rees

LOCATION: Hastings

In 2013 I left London for good. It was traumatic. Fifteen years in that city, longer than any single place I’d lived for the forty years I’d been crawling over the earth’s surface.

In my final years I’d written a book about Hackney Marshes that had taken me deep into my locale in a way I not experienced since I was a child grubbing around the wasteland by the railway track behind our house in Glossop, Derbyshire, well over 10,000 moons ago.

We were moving to Hastings on the East Sussex coast. I knew little about Hastings beyond 1066. It wasn’t really a move towards a place but away from disaster. My wife and I had two tiny kids and a stupid dog and a tonne of debt. Our London bridges were burning down fast and we had to flee, so we fled south.

Hastings seemed an ideal refuge. I’d always wanted to live beside the seaside, which was a strange thought because I’d already lived by the sea for a year in the ‘90s, during my Masters’ degree at St Andrews University. But for reasons that become painfully clear in my latest novel The Stone Tide, that was a year that I had largely repressed on account of what happened to my friend Mike there, his untimely end. It was a year that I recall like a nightmare.

As a symbol of my intent to embrace a new landscape on the south coast, I bought an artwork I had long been coveting: ‘Ghostbox’, an oil painting of Dungeness power station by Bristol-based artist, Hollis, whose work I admired. I loved the brutalist blocks beneath the expanse of sky. An abstract castle, beautiful and menacing. Dungeness is on the Kent coast, but only twenty miles to the East of Hastings, and visible from the town on clear days, which I didn’t realise until after I’d bought the painting.

That painting was meant to represent the future. It was not meant to haunt me, drag me back into the past. I was not in Hastings to be haunted. But that is what happened.

That painting was meant to represent the future. It was not meant to haunt me, drag me back into the past. I was not in Hastings to be haunted. But that is what happened.

It all began with our new house, a wreck in need of renovation. The Stone Tide describes it:

‘Light strobed through moth-eaten holes in the curtains. Cobwebs darkened the corners of walls blistered and pimpled with damp. A stink of rotten earth wafted from the cellar…. Above the front door a cracked stone lintel was the house’s broken heart. Its subsiding interior had the wonk of a eighteenth century galleon. There was an oppressive gravity to the place as if it could no longer bear the weight of its own existence.’

[The Stone Tide, Influx Press, 2018]

So when Hollis’s magnificent oil painting arrived, it was propped in a junk room, covered in bubble wrap, for weeks, maybe months, while we got on with the renovation. Eventually, I couldn’t handle the guilt of its concealment, the pressure to reveal it. One day I unwrapped it and hung it on a wall, amidst the swirling dust and paint fumes.

There it was, Dungeness nuclear power plant – or more, accurately, a pair of power stations next to each other, one decommissioned. It was both in my wall and out there on the horizon, shimmering on the sea, refracted by the haze. On my walks Dungeness power station became a ghostly presence, manifesting on some days and disappearing on others.

I began writing about my walks. My obsession with memorial benches, smoke-dried witches cats and occultist residents of the town.

I began writing about my walks. My obsession with memorial benches, smoke-dried witches cats and occultist residents of the town.

Over the ensuing two years, a book began to take shape from the fragments. It was about how my attempt to investigate the myths and legends of Hastings stirred up ghosts in my memory. The death of Mike in St Andrews, a recollection triggered by the sounds and smells of low tide, the same as they were that day in 1996 when low tide washed him up on the beach outside our house.

As these gloomy thoughts possessed me, freakish storm tides ravaged the coastline and landslip tore away chunks of cliff near the beach. I realised that the Power Station was out there on the edge of England, exposed to the forces of long shore drift, climate change and rising seas. It became symbolic of the world’s end, and of my own rapidly approaching personal apocalypse.

I was horrified by it and obsessed with it.

‘In the distance, Dungeness power station shimmered like Avalon on a bed of mist, pregnant with radioactivity. I felt a great yearning to go there. Not by car or foot but at the helm of a dragon-headed long-ship. Once landed I would go beyond the pylons to the wide sand flats at the end of the world, where there would be nothing but a rim of sea between me and outer space, and I wouldn’t have to worry about any of this.’

[The Stone Tide, Influx Press, 2018]

The Dungeness painting was supposed to represent my future, a new start. But that future was disappearing in this sixth great global extinction. Rising seas threatened to flood the power station, spark nuclear catastrophe and turn the world to waste.

Dungeness was the end times, represented in concrete on a shifting bed of stones beneath a duplicitous blue sky.

It only struck me near the completion of the book that the ghostly presence of the power station in The Stone Tide was as much down to the presence of Hollis’s painting as much as the real thing.

It only struck me near the completion of the book that the ghostly presence of the power station in The Stone Tide was as much down to the presence of Hollis’s painting as much as the real thing.

Perhaps it was the painting that haunted my waking thoughts, not the structure itself.

This phenomenon embodied a central theme of my book: that imagination can haunt you, affect you, change you, destroy you. Imagination is how we prop up our unreliable narratives. It feeds stories you tell yourself about yourself, and also those collective legends of the locale that make a place, and which seep into your reality, until the boundaries blur.

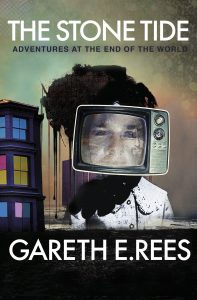

This is what informed the experimental auto-fiction of The Stone Tide. When Influx Press decided to publish it, Hollis was the number one choice of artist to come up with the cover, for one of his works was already embedded deep in the novel, a ghost in the narrative machine.

To see more artwork from Hollis, visit his website here.

The Stone Tide is out now in paperback and limited edition, signed & numbered hardback from Influx Press

Or visit www.thestonetide.com

“The Stone Tide is the funniest, most readable, most intelligently self-searching book I’ve read in years.”

– M John Harrison

“An ‘All the Devils Are Here’ for its corner of East Sussex…”

– Travis Elborough

“It turns out that Hastings is not where psychogeographers go to retire, but to buy haunted houses and go batsh*t crazy.”

– Will Ashon, author of Strange Labyrinth

“A complex map of past lives, hiding places, and scarred psyches.”

– Aliya Whiteley, author of The Beauty

“It’s astonishing and heartbreaking, and possibly invents a new genre: Personal Deep Topography.”

– Owen Booth, author of What We’re Teaching Our Sons

Wow!!

That is great, glad that “Ghostbox” fits into your narrative. Humbled, and happy that it lives with you.

Thankyou!

[…] feeling very humbled that my work can inspire other people, way after it has left my studio. Read the article here. […]