WORDS: Gary Budden

‘It’s hard to paraphrase; if I could paraphrase all this stuff then I wouldn’t have been arsed to write a whole book about it.’

It’s Election Day 2015, and I’m feeling oddly hopeful that something, anything, might change for the better.

Catching the train from London Euston to Birmingham, to then make my connection to Aberystwyth, I walk by endless first-class carriages, running from sparsely populated to empty and silent. An everyday and stark image of economic inequality that I refer to as the ‘pleb walk’; the ordinary passengers forced to walk farther than their first-class cousins just to get on the train. Five carriages of this, to arrive on the packed and unpleasant standard Virgin service. I’m trapped in some laboured metaphor about modern Britain.

The journey out from Birmingham International is better; sparsely populated Arriva trains (it is a Thursday after all) trundling slowly into Wales through fretful and unpredictable Spring weather. I pass through areas I have stayed before, recognising signs for Machynlleth and remembering the gorgeous emptiness when I stayed in Llanidloes, eighteen months back.

I’m on way to meet the novelist Niall Griffiths, who I will admit has been something of a personal hero ever since I discovered his novels in my second year of university, faraway in Norwich, circa 2002. That first book I read was Kelly + Victor, a sobering, demotic novel set in Liverpool at the turn of the Millennium about a sexually extreme love story, written in incandescent and visionary language; it’s as great a place to start as any, but it was the second novel of Griffiths’ that I picked up, his debut Grits, was the one that really sold me. Even the cover seemed perfect, with a bunch of scruffy looking types loitering on a stony beach, looming mist-shrouded mountains on the back. A five hundred plus sprawl, Grits was for me a literary epiphany, showing me what was possible to do with the novel, a merging of that ordinary/marginal/working class voice found in Irvine Welsh and John King, but coupled with the grand ideas of psychogeography and a real, hypnotic attention placed on the effect of landscape on the human psyche. What made it so important for me was that the psyches in question were not those of sensitive poets, eccentric writers or members of the English middle-class.

I’m on way to meet the novelist Niall Griffiths, who I will admit has been something of a personal hero ever since I discovered his novels in my second year of university, faraway in Norwich, circa 2002. That first book I read was Kelly + Victor, a sobering, demotic novel set in Liverpool at the turn of the Millennium about a sexually extreme love story, written in incandescent and visionary language; it’s as great a place to start as any, but it was the second novel of Griffiths’ that I picked up, his debut Grits, was the one that really sold me. Even the cover seemed perfect, with a bunch of scruffy looking types loitering on a stony beach, looming mist-shrouded mountains on the back. A five hundred plus sprawl, Grits was for me a literary epiphany, showing me what was possible to do with the novel, a merging of that ordinary/marginal/working class voice found in Irvine Welsh and John King, but coupled with the grand ideas of psychogeography and a real, hypnotic attention placed on the effect of landscape on the human psyche. What made it so important for me was that the psyches in question were not those of sensitive poets, eccentric writers or members of the English middle-class.

I’m fascinated with how landscape shapes the human psyche; whatever generic label you want slap on the kind art produced in response to the very real psychological effects landscape can have on the person. Psychogeography, deep topography, nature writing, flaneurism, whatever, it doesn’t matter.

In the literature of place, in all its guises, I always had a nagging problem. Undoubtedly there was a dominant voice in this nebulous genre. Things are changing now for the better, but the documenting of the experience of place can at times seem to be the preserve of, if not an elite, then a certain type of white British male of a certain class. Griffiths’ novels were the first books I read that showed me things didn’t have to be that way. That the experience of the ‘normal person’ – or even the perceived dregs, the scum, the punks, hippies and ravers, all those marginal and unheard voices – could be given searing, life-affirming voice.

All of his novels follow in this vein to some degree, featuring overlapping characters, creating a shared internal universe of heightened senses and visionary landscapes. Sheepshagger and Runt especially use the landscape of west Wales to stunning effect.

After what seems an eternity, re-reading my favourite sections of Grits on the train and counting the number of little egrets and buzzards I can see out of the window, I finally pull into Aberystwyth where I’m meeting Niall. I spot a red kite floating over gorse and grass up on the rugged hillsides. After checking in to the tiny B&B (featured on Four in a Bed, apparently) we head to a pub on the seafront, sit outside taking advantage of the sun, looking out over the Irish sea and the blue-grey pebbled beach. Then through the gorgeous ruins of the 13th Century Aberystwyth Castle – strange to be standing in the physical place I’d understood through fiction.

After what seems an eternity, re-reading my favourite sections of Grits on the train and counting the number of little egrets and buzzards I can see out of the window, I finally pull into Aberystwyth where I’m meeting Niall. I spot a red kite floating over gorse and grass up on the rugged hillsides. After checking in to the tiny B&B (featured on Four in a Bed, apparently) we head to a pub on the seafront, sit outside taking advantage of the sun, looking out over the Irish sea and the blue-grey pebbled beach. Then through the gorgeous ruins of the 13th Century Aberystwyth Castle – strange to be standing in the physical place I’d understood through fiction.

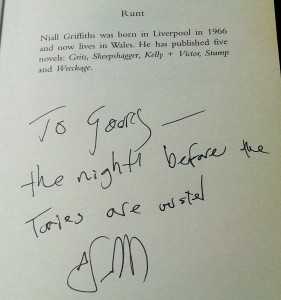

The first question I ask Niall, after drifting round a number of the pubs and bars in Aberystwyth engaging in lengthy diatribes against the Tories and talking about the return of red kites to Britain’s skies, is, naturally, about the role landscape plays in his work, with the Welsh landscape in particular.

‘It’s become a bit of a cliché to say that the landscape or the city’s a character. What it came from was when I lived in Liverpool, I was quite a naughty kid and I’d done lots of attendance centres and that kind of stuff, and once I broke the law – I can’t remember what it was – and I got sent to the same magistrate. He said ‘I’ve seen you before Griffiths, I’m going to send you on an Outward Bound course’. I’m sure the Daily Mail would hate this, but it worked, it really did work. So they took me up the wilds of Snowdonia.

Does this bear relation to a strikingly similar scene of naughty kids up a mountain in Sheepshagger?

Yeah it’s very similar. You had to fend for yourself and they left you alone. I remember sleeping by the side of a lake. I remember hearing the sound of the rain on the tent, and the noise of the hawks and the owls. The countryside at night-time is not a quiet place, it’s fucking loud, but it’s quite beautiful noise. I remember feeling quite at home (we’d go to North Wales a lot anyway, but to the towns to see relatives). After that, all my urges to run wild, to go mad, to vandalise, I was able to filter them through this urge for a wildness that reflected my own internal dissatisfaction. I would often just take myself off with a sleeping bag and a penknife and go into the North Walian hills. I learnt to eat roots and berries and things – I was only 18/19 at the time, it’s easier to survive at that age! – and taught myself all this stuff.

So yeah the landscape is a character in the books, but it’s also the book itself.

I agree with this; I suggest more than anything that Grits is the mountains, the landscape that surrounds this town, and the town itself.

It’s hard to paraphrase; if I could paraphrase all this stuff then I wouldn’t have been arsed to write a book. But to find a kernel of where it all comes from, to see the figure of human being in the shape of a mountain is to recognise that it’s all part of one, it’s all wildness, it pays no attention to history in a way (even though history is very, very important) it means that the passage of human life is nothing compared to the passage of a mountain. Once you align the passage of human life with the passage of a mountain you make that life epic, no matter what it is, whether it’s the life of a junkie or whatever, you make it epic. That’s what I’m always trying to do.

The Welsh language too, it’s beautiful in the way it sounds like the landscape it describes, like the place where it’s from.

The language reflects a place?

It’s inextricably linked.

I ask about the link between what me might call ‘deep time’, geological time, allied with contemporary issues, for example the imaginary psychogeographical text, A Personal Guide to West Wales, which intersperses the various characters narratives in Grits, and how this ties up with ancient, and more modern human histories – how all this impacts upon the psyches of the characters. They are a product of all of these histories?

When I first came here, I remember walking up on the hills above where I live now and reading the landscape. I got the sense that the very first narratives in this landscape were made millions of years before humans. The passage of birds across the sky or the passage of little animals across rock, but when the rock was mud. This notion of a vast geological time and how trivial our little ideas are.

And yet we are here and have to live these trivial lives.

Of course. Nearly everything I write is political, but it’s the notion of the petty little squabbles that politics has…it’s just nothing. In fact, what my characters have is this… there’s a quote from Grits that explains what I’m saying: Perhaps we can see and hear in them whole continents breaking apart.

What they fight against, in their own souls, even though they’re seen as ‘little’ lives in the general media, is much closer to continental drift or seismic shift than all of the petty little squabbles of politics. So in that way I’m trying to give my characters a life not only of epic grandeur, but that is very close to the movement of mountains. So grand and so important and at same time swallowable and dissolvable in the movements of the Earth.

Metaphorically, you can see or feel tectonic shift inside yourself? It happens almost imperceptibly slowly, but when it’s done you know you have changed?

Yeah. There’s dichotomy of: do I stay straight and in pain, or do I get wrecked and achieve ecstasy?

I ask is there a knowing influence of psychogeography in the writing? I know Iain Sinclair gave Sheepshagger a glowing review, and I’m thinking of people like Arthur Machen (a Welsh writer) who might set some precedents. The fact you can’t remove the individual from their environment seems to be a key idea in your novels.

I’m a bit wary of the term psychogeography – the phrase suggest sandals and muesli – and I’m trying to get to something much more visceral than that. But yes, of course it’s in there.

The follow on point is that whatever we might call ‘traditional’ landscape writing was the preserve of the middle to upper (male) classes. Where does your focus of subcultures and people from the ‘underclass’ come from? Was it an experience you thought pushing as an issue?

Yeah absolutely. I found it a very Welsh thing too – a reaction to books like How Green Was My Valley by Richard Llewellyn, where the main character is called Ianto [the name also of the protagonist in Sheepshagger]. This whole notion of things like ‘Above Tintern Abbey’ – we’re above, only observing. There’s a quasi-imperialist attitude: that the Celtic countries, and the north of England, in the rural north, that we’re all fine, we all live in harmony with nature, we all spend our days in the fields, drink a bit of cider and then we go to the hearth and tell stories.

Something that was never true!

No. Even the rural side of it all, which did exist of course, was never idyllic. There were things like footrot and ticks and substance abuse. It was always there. It’s not a mental or physical space for the urban put-upon to retreat to. It has its own fucking problems. I find it deeply offensive this idea that Wales is the playground of the rich, and this has become even more important. It’s partly why the Tories want to hold onto Scotland so much, it’s a place where they can go and shoot animals, it’s their playground, and Wales is the same. There’s a very political aspect to it. It’s fundamentally political, anti-imperialistic, to show the rural life in all its bloody, brutal beauty.

There’s a term used now, ‘anti-pastoral’ writing, that’s being applied to writers like Cynan Jones and Ben Myers that are doing a similar thing to you, escaping from that clichéd idyllic view of the countryside.

It’s always been there. It goes back to Hardy. Hardy’s countryside was a place of pain and suffering and misery. Hardy was even bleaker than I am, I think! In the sense that the natural world is not just indifferent to you but actively hostile to you. It’s terribly bleak. Hardy is now seen as a pastoral writer, which baffles me.

Do you think that’s an issue of style perhaps? I’ve seen a number of reviews comparing these ‘anti-pastoral’ novels to the works of American writers, most notably Cormac McCarthy. Grits even has a section with the character Colm at home reading Suttree. Is there in any way a sense of that American style being partly adapted and filtered through a British experience?

Absolutely. Part of the genesis of Sheepshagger was reading Child of God by McCarthy and thinking ‘why has no one done this in Wales, in Scotland or Ireland?’.

Are there precedents for this kind of writing in Britain? Ron Berry perhaps? There’s a ton of British nature and landscape writing, but not necessarily in this style, as far as I’m aware of.

Are there precedents for this kind of writing in Britain? Ron Berry perhaps? There’s a ton of British nature and landscape writing, but not necessarily in this style, as far as I’m aware of.

I think you’re right. Which means I founded a new school of writing and therefore I’m eternal!…but no I think you’re right. My influences are more American than British. There are, I suppose, similarities with things like Straw Dogs, the backwoods horror, but those are all the about the attack against the incomer. There’s an element of that in the novel, but in Sheepshagger what does he do? He doesn’t attack the people who are oppressing people, he just attacks people who are a bit petty.

He attacks the weak, doesn’t he.

Yeah. The people he kills, if they’re guilty of anything, it’s of being pretentious. They don’t deserve to die. Mappable politics is an irrelevance; it’s just pure anger. An anger at this notion that the wildness in the human has been swamped by conformity and blandness.

Not tamed, just pushed down.

Never tamed. Trained, but never tamed. And it’s got to burst out somehow. Along with that a, not religious exactly, but spiritual notion for recognition from God, for some spiritual recognition. If that is always blocked it will eventually come out in some way that makes you feel alive and fierce; and it could be violence.

*

I woke up the next morning bleary-eyed in the B&B to a beeping phone, texts informing me of the Tory win. It was a kick in the balls, gutting. But thinking of what I’d been talking about the night before and looking out over the sea before I got my train, it felt hard to think that all was lost.

Gary Budden is co-founder of independent publisher Influx Press and assistant fiction editor at Ambit magazine. He lives in London. Click here to read his blog: New Lexicons.