WORDS: Gareth E. Rees

In 2001 I became a weekend DJ in Filthy McNasty’s, a pub in Islington, sadly no longer with us. I was paid in beer to put one song on after another, while the pub ebbed and flowed with drinks, drugs, hugs and shouts.

Filthy’s was a hub for artists, writers, musicians, gangsters, drunkards and eccentrics. I arrived after the Pogues years, when MacGowan and co. could be found drinking, but during the Libertines years, where Pete Doherty and co. played often before being signed.

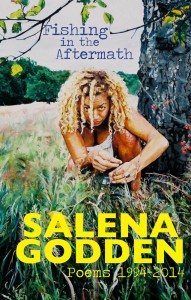

That was where I first encountered Salena Saliva, as she called herself back then. Over the ensuing years I’d bump into her at various gigs and parties in Soho, Camden and Clerkenwell. I even joined her on a leg or two of her drinking adventures. I watched her perform many of the poems in her newly selected works Fishing in the Aftermath: Poems 1994-2014.

She was warm, bold and brilliant. The life and soul. The poems were honest, dirty, funny. They spoke of an artist’s life, tumbling in and out of bars, class A’s at oddball parties, sexual encounters, weird walks home, comedowns and rundown flats.

After I had kids, that London landscape faded into a sepia memory for me. When I wasn’t working or keeping babies alive, I wandered Hackney marshes with my dog. I stopped bumping into people like Salena.

But I’d hear her on Radio 4, occasionally sounding hoarse, and I’d wonder what she’d been up to the night before. In my imagination she was still out there, rallying the troops, leading from the front, fighting the good fight, drinking and loving.

I could never understand how she got so much writing done. It was heroic, really. I never wrote a damned thing with a drink in my hand, nor with a hangover neither. But still I missed that old gin-soaked London and the people still rattling around in it.

A woman in search of a fiction

Of course, there was ‘Salena Saliva’ in Bukowski mode, a fictional character she developed on the hoof, and performed on the city’s stage. Then there was the fiercely disciplined Salena Godden who locked herself away for days and laboured at her poems, turning her experiences into art, musing upon the joy and suffering of writing poetry, as she caustically puts it, “the poor cousin at the wedding of real writing”.

Both versions are represented in Fishing In the Aftermath. There are poems about her travels, inspirations and politics, but for me the London poems are particularly anthemic, because they illuminate the city of the gutter romantic, steeped in booze, raw spirit and camaraderie.

This is London

and it’s raining

Sex and drink.

These poems speak about an experience of the City I once understood. Pubs feature regularly, the kind like the old Filthy McNasty’s, which the gastro chains are killing off.

In ‘Eyes like wood lice’ we encounter “suicide central / patrons found in the toilets in tears / as grown men sobbed onto their soured-milk beers”. In ‘The Saturday Shift’, at a wake for pub regular Old Reg, there are “sausage rolls on a plate”.

Godden describes plenty of those random encounters you get wandering the city. In ‘Emily’ she swings from the bars on the Piccadilly line with a complete stranger she befriends, then accompanies home.

Now, I remember the sun rising in Islington

the pavement shone with gold

Seen through a boozy prism, London becomes a land of infinite possibility, dazzling and strange.

Most decadent of all is ‘The Last Big Drinky’, a prose account of a seven day bender led by ‘Saliva’ and described from the point of view of her friend. They enjoy beer in the pub (“London is thirsty, good because we are having a drinky”) then it’s back to flats for vodka, Mexican liberty caps and a frenzied threesome, followed by Baileys for breakfast. They’re stared at as they stagger down the street, out of step with families and commuters.

At the end of it all Saliva passes out with “seven days of alcohol in her thick syrupy blood”.

That’s when the terrors come.

That’s when she declares, “I don’t want to be Saliva any more”.

The arc of Godden

There’s an implicit story arc in Fishing In the Aftermath – inevitable, really, if you collect someone’s confessional poems over 20 years. Much of the wild experimentation of the young seeker gives way to sobering poems about the process of ageing and readjustment.

The question is, what happens the drinkers, carousers and late night performers get older?

Now there are babies and debts and deadlines,

filthy habits and foul coughs,

eccentricities. we once found charming

stain our crooked teeth and leave a sour taste.

We’ve all put weight on…

In ‘All We Can Do Is Hope’, the poet stares into Amsterdam’s dirty canal water, seeing the reflection of drunks and has an epiphany:

I am not who I thought

I was.

I looked for myself but I was not there or here, not anymore,

It is the nature of things to grow and change

I forgot that included me.

But at the end of it all,when all is said and done, Godden is still writing and performing. She has made it through the process of living your art and making art of your life. She’s alive and well and kicking, still.

You can find out more about Fishing In the Aftermath here

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gareth E. Rees is the editor of Unofficial Britain and author of Terminal Zones (Influx Press, 2022) Unofficial Britain (Elliott & Thompson, 2020) Car Park Life (Influx Press 2019), The Stone Tide (Influx Press, 2018) and Marshland (Influx Press, 2013).

Buy this book – you will not be disappointed. Salena Godden is gorgeous graceful grim grinning reality made flesh and come to walk among us.

Hi Gareth

Good article. You and your wild youth. I didn’t know you knew Salena back in the day.

Hope all well in Hastings. Currently on the Isle of Wight (my birthplace) with Martin. Be good to see you and Emily again soon.

Rowena

Agreed, Andrew, that’s a nicely alliterative way to put it!

Cheers!

Gareth

Salena is little changed by years. very much kicking