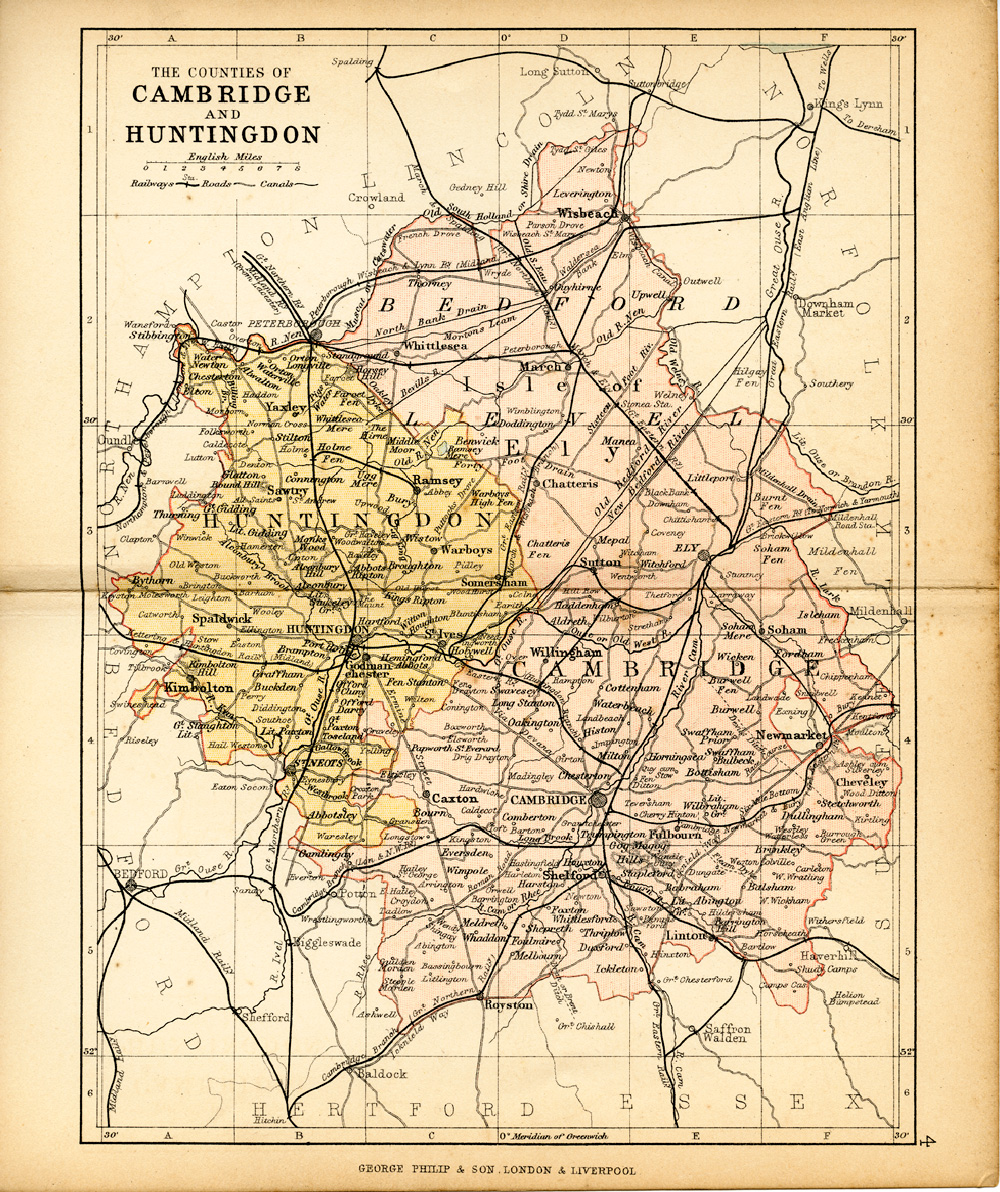

LOCATION: Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire

LOCATION: Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire

WORDS: Paul Case (with help from Glen Reid)

It’s 2004. Glen and I sit in his front room, gazing over our purchase of two bags of magic mushrooms. In April 2005, the Drugs Act will be passed, rendering mushrooms illegal. Until then, though, they are available from the closest provincial hippy paraphernalia emporium.

The woman at the counter told us we should eat them on empty stomachs. Accordingly, with bellies rumbling, we wolf them down, battling through the bitter taste with mouthfuls of chocolate.

We wait a while, silent and nauseous. Some nu metal video on MTV2 is on, featuring a chubby white guy singing about self-harm. In years to come, I’ll play these songs and pretend I never enjoyed them.

Without warning, my bowels loosen. I rush to the toilet.

Washing my hands and staring into mirror, the first wave of mushroom high hits me, coated in post-dump euphoria. I head downstairs, gripping the banister for balance. Glen is entranced with the TV, with twinkling eyes and an unconscious smile.

It’s time to explore.

*

We live in Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire. In 2015, my partner will visit with me and proclaim it’s “basically a village”, but I dispute this – by then it will have a Costa, making it, if not a big town, then definitely a medium sized one. However, there’s always been plenty of green space for two hallucinogen novices to meander about it in, albeit hemmed in by suburban estates and the dim roar of motorways.

The mushrooms, not strong but strong enough, seize us as we bumble through the night. We gabble and procrastinate, stopping every few moments to stare dumbly as the most banal things become utterly engrossing.

We’re heading for the petrol station. Our final destination is Hinchingbrooke Park, where grassland and woods await us, but even though our stomachs are nothing but tiny burbling cauldrons, we have an impulse for junk food.

The automatic doors slide open and we step into the overwhelmingly bright light. Cold reality slaps us in the face. It’s like waking up in the middle of our own autopsies, all the mystery just stripped away. Tinny bhangra plays somewhere in the background, an incongruous accompaniment to the clinical whiteness of the shelves and their microwave burgers and their extortionately priced sandwiches. The shop assistant looks up at us. We look back at him, freak out and hide in the confectionery section.

Paranoid of making a scene, whispering and huddled as if in the midst of guerilla warfare, we begin to strategise a path of least resistance. After a few seconds of this, I’m suddenly hyperconscious to the idea that we might look quite strange. I slowly rise to peer over the shelves. The shop assistant is staring right back at me, utterly bemused at what he must only assume is a bizarre shoplifting tactic. I duck down immediately.

After some frantic, hushed decision making, we decide to bite the bullet. We stand together, arms loaded with crisps and chocolate, and do an impression of a confident march to the till. The shop assistant looks over us wearily. We bundle over a random selection of coins, and hope. It seems to work. We offer hurried thank yous, grab our haul and scamper out into the comforting cool darkness.

With only the half-moon for light, we cut across the cow field. It’s always oddly absent of cows. The grass shifts in glowing iridescent patterns around our path.

Emerging on to the main road, occasional orbs of street lights hang over us now, guiding each giddy misstep. Hinchingbrooke Hospital looms ahead. As we pass, its entrance appears as a flaming portal to the underworld for damned wanderers.

In 2011, under the Labour government, it will become the first privatised NHS hospital. In February 2015, the Care Quality Commission will put Hinchingbrooke Hospital on special measures, citing inadequate health and safety standards.

We keep our heads down and hurry on.

Past the hospital’s leering menace, we arrive at a road we’ve never seen before. Our curiosity and nervousness aroused, we make a tentative decision to investigate. The street is lined with pristine two storey houses. It’s abnormally still and silent. We tread lightly in the middle of the road. We mutter in low voices. Something’s missing.

We slowly realise there’s not a single light on in any of the houses. There are no cars in any of the driveways. None of the windows have curtains, and suddenly there’s a series of vacant dark eyes tracking our every move. A creeping, confused disquiet crawls over us. It’s like touring a museum of our present.

In a vague attempt to solve this mystery, we summon up the courage to inspect a downstairs window. An empty room, which in another state would be a living room, stares back at us, solving nothing.

After a few minutes wandering, the houses on our right disappear, and are replaced by a two metre tall double fence. The change in scenery disturbs our pace. We stop, taking in the ominous trespasser warning signs. We edge closer. I have an impulse to climb over before I notice the twisting barbed wire on top.

Fingers curled through the diamonds in the fence pattern, we look on to a vast concrete car park. Huddled in the centre is a large, anonymous one storey building. A few of the windows glow with sterile light. This is the first glimmer of activity in what seems like a long time.

We follow the fence until we reach the entrance, a huge gate with a uniformed guard sitting in a small booth, his face a luminous blue from the security camera screens. His eyes trace over us for the briefest moment before going back to his work. Glen and I retreat to the other side of the road, engaging in yet another muted exchange. What the hell is this place? A top secret military facility, hidden in the hinterland between the suburbs and the woods? Cambridgeshire’s Area 51? It does kind of make sense… there’s a load of air bases around this area…

We have to know. We can’t have this weirdness churning our brains all night.

In a burst of brazen, self-righteous confidence, I decide to simply go and ask. Glen, wisely, stays skulking in the background. As I approach, the guard steps out of his booth.

I figure the chirpy approach would be best to coax information out of him.

“Alright mate?”

He looks me up and down.

“Good evening, sir,” he replies flatly.

I notice he has a gun slung around his shoulders.

He’s holding a fucking gun.

I’m way out of my depth but I plough on, indulging in what I think is hilarious improvised comedy. But like most improvised comedy, it’s deeply misguided.

“What’s going on here then?”

“I’m afraid I can’t tell you that sir.”

“Ooh, that’s very secretive,” I respond, with a tinge of inexplicable camp.

He steps forward, coolly fixing me with a jaded, threatening stare. His hand tightens on the grip of the gun.

“I’m going to have to ask you to leave now, sir.”

I weigh up my options. There are very few.

“Yes, fair enough.”

As Glen and I beat a hasty retreat, we imagine a sniper’s crosshairs tracing the back of our heads. We amble a little more but the night has peaked. The mushroom high dissipates into tiredness. We leave the edges of town to scurry into hiding as dawn approaches. Hoods up against the early morning chill, we walk in silence, tracing familiar routes home.

Paul Case is also known as performance poet, storyteller and singer Captain of the Rant. He has performed all over the UK and internationally. Website: http://captainoftherant.wordpress.com

Glen, or Lenny, Reid is a very great friend and an upstanding gentleman of much insight and wit. You can follow him on Twitter here.