WORDS: Adam Smith

There exists an alternate version of Britain, one which I am totally fascinated by. In this alternate Britain the national mood never shifted away from the scientific primacy and modernistic optimism of Tony Benn – rendered concrete and revolving restaurants.

In this Britain, the civic plans put together by dozens of city planners went on to be realised in their entirety instead of consigned to the ‘what if?’ pile of social and architectural history.

Today I want to take you on a tour of one city that looks quite different in this alternate Britain: that city is Bristol.

Around the mid-1960s, a slew of plans were issued by Bristol City Council, envisaging a rebuilding of the city with little consideration for existing buildings, neighbourhoods and street patterns.

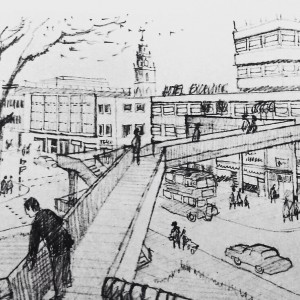

Our tour starts in an eminently logical position: in the Centre. In ‘Real Britain’ the Centre is a pedestrianised plaza with fountains, a dozen bus stops and a view down toward the restored dock-side warehouses. It’s the epitome of a modern attempt to create pedestrian-friendly space.

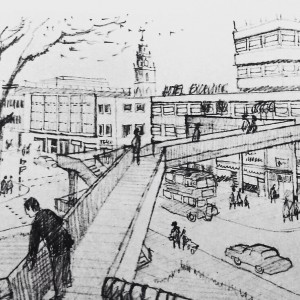

But here we are in the Centre of an alternate future…

But here we are in the Centre of an alternate future…

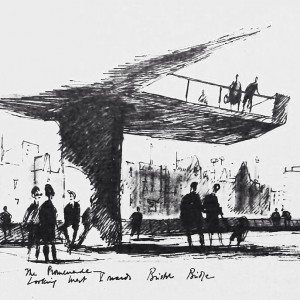

Instead of walking on street level we find ourselves raised above the ground on a concrete highwalk devoted entirely to pedestrians. Below us, the edge of the quay shows where limestone deposits have dripped out from the concrete and formed stalagmites on the pavement.

Take a moment to lean against the metal railings and look out over the water…

A resident of the ‘Real Bristol’ would be shocked to see those old trading warehouses demolished and a new road crossing over the muddy-brown water of the Floating Harbour. Indeed, the 1966 City Centre plan for Bristol envisaged a new network of urban motorways circling and crossing the city from all corners.

Remnants of the plan can be found in today’s Bristol. You can see it in the sweeping curves and split-levels of the roads crossing Cumberland Basin.

In Alternate Bristol this no-holds-barred approach to road building is replicated across the city. Cars barrel round the new inner ring road, vaulting over grade-separated junctions built on top of rows of razed houses in Totterdown or careering downhill on a smooth dual carriageway from Clifton Triangle to Southville.

Instead of petering out in the city centre, the M32 motorway glides into town with strands of traffic veering off left and right, unimpeded by such things as traffic lights, pedestrians or pre-existing buildings.

Instead of petering out in the city centre, the M32 motorway glides into town with strands of traffic veering off left and right, unimpeded by such things as traffic lights, pedestrians or pre-existing buildings.

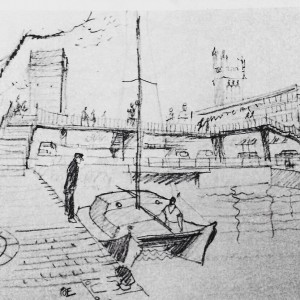

With Alternate Bristol’s infrastructure reshaped by new roads and pedestrian high walks, it lands on Hugh Casson, the esteemed architect and master planners, to reimagine the derelict docks in the south of the city centre.

The Casson plan removes any trace of the warehouses, cranes and rail yards that were somewhat preserved in the real-world regeneration. Instead it takes full advantage of the new road network by building a maze of slip roads and through roads at ground level with warren of concrete, glass and steel on top.

I invite you to come and stand with me in the alternate Canon’s Marsh: walk with me to the edge of the rooftop squash courts and look down to see the traffic rushing by below. Look across at the glass-walled office blocks belonging to de-centralised QUANGOs. Step across yet another concrete highwalk to glimpse, across the harbour, at the majestic SS Great Britain, clipped by another dual carriageway diving over the docks.

To imagine Alternate Bristol fully, start with what did happen to the very heart of Real Bristol. Look at Lewin’s Mead, Rupert Street and (if you knew them before their recent demolition) the walkways around the Magistrate’s Court. See the slabs of flats and bridges over unfriendly roadways and extrapolate that across the entire city centre.

To imagine Alternate Bristol fully, start with what did happen to the very heart of Real Bristol. Look at Lewin’s Mead, Rupert Street and (if you knew them before their recent demolition) the walkways around the Magistrate’s Court. See the slabs of flats and bridges over unfriendly roadways and extrapolate that across the entire city centre.

The difference between Alternate and Real Bristol lies on the same dystopian/utopian fault line as dozens of unrealised plans for cities across Britain. Where we see elements of the 1960s’ plans put into place: in the underpasses and roaring traffic of the Bearpit roundabout or the soon-to-be-demolished Entertainments Centre, we might be more inclined to argue that those plans were an abject failure.

But take a moment to think about Alternate Bristol – indeed Alternate Britain…

Public opinion never changed against ‘concrete carbuncles’ and ‘city centre eyesores’. We bought more fully into the ideas of subways and highwalks which councils maintained with pride. We learned to love our ‘streets in the sky’.

Here you are looking at the Britain that these plans were drawn up in, and perhaps this Britain, full of hope and idealism, bold visions and bolder shapes, is the Britain those plans should be judged in.

Adam Smith is a writer, student and curator of interesting things at Common-or-Garden. He tweets @nfkadam and is currently working a book about failed post-war plans for Britain’s cities.