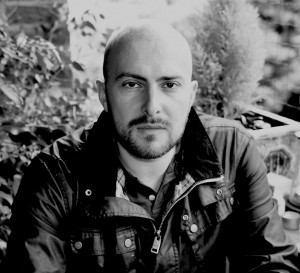

WORDS: Gary Budden interviews Rob Cowen

WORDS: Gary Budden interviews Rob Cowen

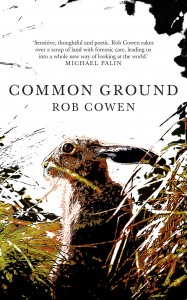

I recently spoke to Rob Cowen, author of the excellent Common Ground, about his new book, edgeland literature and psychogeography, the debates around what does and does not constitute ‘nature writing’ and the importance of writing in re-engaging people with place.

*

RC: I kind of strayed into psychogeography without really meaning to. I’ve always been looking for a way of understanding the greater, broader, deeper aspects of landscape and our connection with it. I’ve always read books about landscape because that’s what I grew up reading.

Psychogeography to me is like a field that I got to through a long walk through a wood. It was somewhere that I immediately felt was interesting. But it’s nothing new. The myth is that it’s something new.

In Richard Jefferies The Story of My Heart (his mad, rambling, crazy, brilliant autobiography), he spends the first 40 pages of that book talking about walking up a hill in Wiltshire, being by a burial mound and having the sensation of thinking about the body and the burial that’s 3000 years old, thinking about the butterfly moving between the cornflowers and the bees between the bindweed, and then the stars, and then a kind of ultimate time. He describes that over 40 rambling pages – but brilliantly he ends that whole section by saying ‘of course, all of this comes to me in one second of being there’. That to me is no different to psychogeography.

GB: I like that. John Rogers [author of This Other London] talks about not only the French flaneurs, but the English topographical writers of about a century again, people like Gordon S Maxwell – doing a similar kind of thing.

RC: Maxwell, we had his book on the shelf when I was a kid. The thing is, that approach always made more sense to me than the sterile field guide, or the pictorial guide for walkers or climbers, or whatever it was. The sense that the landscape was somehow living and breathing. As I say in the book, there’s a kind of aboriginal concept of the land as being a repository of memory.

I mean that firstly in a kind of pseudo-science way – how is that different people can walk through the same space that they’ve never been to before and experience the same range of emotions? But I also mean in that the sense that there’s no way that we, being so receptive as a creature, can fail to start noticing things all around us. For example, I was watching hares. Every time I’d sit in the field and watch hares, I’d find bits of broken clay pipes from workers, find old horseshoes and bits of broken pot. You can’t help but feel the lives and layers.

GB: The layers then start to build up, don’t they.

RC: They do. This links into the debate about land generally. There’s nothing other than common ground, there’s no landscape that isn’t interfered with, whether that’s industrially or intensively farmed, or indirectly, though our actions in terms of our effect on the wider environment. I think it’s dishonest to talk about landscape in a rarefied and separate sense.

GB: This idea of wilderness – wilderness doesn’t really exist any more?

RC: A classic example is Everest, held up as the ‘great extreme wild’. You look at pictures of Everest there’s always a queue of 300 people trying to climb it and it’s full of cans and gas cylinders . . . it’s a wreck.

Our connection to landscape is complicated, it’s profound and it’s emotional, it’s physical and instinctive and it’s augmented. It’s all these different things together. What I love is books that try and ask a question about that.

With Common Ground, at first I thought I could just write following the course of a year, a year in this place tracking the change of seasons and so on. I could easily have written a book like that.

GB: There are quite a few of those books.

RC: Yeah and they don’t really do it for me to be honest.

GB: I find them, often, a little bit twee and English…

RC: It’s like what Kathleen Jamie said, nature isn’t all primroses and otters.

What put me off that form is that it didn’t feel like it was an honest representation of place. As soon as I found the edgeland I wrote about, I got a very real sense that it was tugging at my sleeve, and going – ‘don’t forget’. This place is going to vanish in 15 years – who’s going to know anything, remember anything about the place?

GB: This leads me onto the stylistic choices in the book – that mix of memoir, social history and fiction (something that appealed to me greatly about the book). Taking the one perspective isn’t enough?

RC: There are many ways of telling a story. I could have written a social history of that place and it would have fulfilled a function of some sort. But it wasn’t what I felt. I couldn’t get across what I felt that way, what it was like to spend a night in the dark there, in the shadow of 70,000 houses, in a strange and wonderful, dark, deep place. That approach just wasn’t going to cut it. So then what do you do?

I knew for the first chapter, that the fox perspective was important. It was a symbolic creature in the sense that this creature is one that crosses between worlds. But this was a fox I was following that didn’t venture into the urban; it stayed in the edgeland. It wouldn’t go in. It was like a last vestige of something on the edge itself. The last wild fox on that bit of ground. Ultimately this would kill it, it was starving and made bad decisions, but couldn’t cross over.

GB: It’s interesting you use the word ‘wild’ there to describe it. Surely all foxes are wild? Are urban foxes ‘less’ wild?

RC: They’ve changed territory and I think they’re more familiar with people. Urban foxes don’t run from people; I’ve stood in London with an urban fox stood just two feet from me. But watch a fox in a wood and will disappear like smoke, because it won’t want to be anywhere near you. That’s instinctive.

It seemed relevant to me to try and capture the experience of that fox, to try and explain its perspective and to explain this crossing place, this meeting of the urban and rural. This weird tangled place, this margin place. It needed another voice other than my own to try and explain this place. I taxonomised it in a human way; I talked about the railway and the viaduct and how this place was created, but that wasn’t the whole story. There was an animalistic rawness that existed on the edge as well.

GB: Did you find it hard to write the fox section? I find there’s often a risk of sentimentalising or anthropomorphising when writing an animal’s account of things. Could people associate that kind of writing more with children’s literature, or books like Richard Adams’ Watership Down (which incidentally I like very much)?

GB: Did you find it hard to write the fox section? I find there’s often a risk of sentimentalising or anthropomorphising when writing an animal’s account of things. Could people associate that kind of writing more with children’s literature, or books like Richard Adams’ Watership Down (which incidentally I like very much)?

RC: Not really. Before I’d even started writing the book I had about 150,000 words of field notes. A lot of that was just recording and following. So I already had the scenes, if you like, that were going to occur, because I’d watched them happen. Something happens when you begin to spend a lot of time outside – you begin to empathise in a different way with the natural world. I found it very easy. I’d love to say I struggled with it but I wrote it all in, pretty much, one continuous session. I did feel at times that I was merely channelling something.

I was conscious of that Henry Williamson Tarka the Otter thing. But what he does brilliantly is make you the reader feel like you’re crawling along the bank of a river. I wanted to create the same feeling [with the fox section]. Richard Adams created the same feeling in Watership Down – it didn’t seem contrived, you immediately lose yourself in the narrative.

It’s the same with the chapter on the deer in Common Ground. I feel that that section is totally true. I felt that there was a way to present the book in an interesting, different way. I don’t really care about form, that’s my problem. I don’t really sit down and think ‘Is this nature writing? Am I crossing some sort of event horizon where this no longer becomes nature writing?’ That never occurred to me. I just wanted to write a book about people and about place, and be honest. To somehow capture the essence of a place in a way that, to me, many defined genres do not do.

GB: So what do you think about recent negative articles about the ‘New Nature Writing’?

RC: It seems a bit silly to me. To try and define nature writing under very certain terms is a stupid thing to do. Nature writing is as old as writing itself. Take ‘The Seafarer’ from the Exeter Book [Old English poem], 960 AD, with the narrator talking of his heart-strings being tugged and the cold grains of snow coming in – read that poem, it’s personal, combining his feeling of being on the sea and away from home, how the elements affect his emotions.

Edward Thomas was personal. Read The South Country, if you want to talk about psychogeography. That book is classic exercise in psychogeography. He moves with a fluid dynamism and freedom between personal narrative and, basically, a novel. There’s an entire chapter in that book based on what he overhears on a train. It’s clearly dramatised. It crosses between his feelings about enclosure and what’s happened to the countryside, his personal feelings about nature . . . people have been doing this since time immemorial. Richard Jefferies’ The Story of My Heart is one of the most personal accounts of nature ever written. It seems to me that for the new generation of nature writing, to try and batten down the hatches and say ‘this is the genre, it should be removed, be about nature and nature only, with an absence of the human’ seems impossible to do.

Edward Thomas was personal. Read The South Country, if you want to talk about psychogeography. That book is classic exercise in psychogeography. He moves with a fluid dynamism and freedom between personal narrative and, basically, a novel. There’s an entire chapter in that book based on what he overhears on a train. It’s clearly dramatised. It crosses between his feelings about enclosure and what’s happened to the countryside, his personal feelings about nature . . . people have been doing this since time immemorial. Richard Jefferies’ The Story of My Heart is one of the most personal accounts of nature ever written. It seems to me that for the new generation of nature writing, to try and batten down the hatches and say ‘this is the genre, it should be removed, be about nature and nature only, with an absence of the human’ seems impossible to do.

GB: The act of writing itself makes it human.

RC: Yeah. So of course it’s already going to have the influence of the human. But also we are inseparable from nature. I always think if you want to kill a genre, putting fences around it and saying ‘this is it’ is a way to make it irrelevant, boring and stale.

GB: There’s a whiff of elitism about it?

RC: Yeah there is.

GB: I wonder who even coined the term ‘New Nature Writing’.

RC: Probably the press. ‘Nature writing is the new rock’n’roll they said a few years ago. The analogy I use is that it’s a lot like the folk scene in 1960s Greenwich Village New York, at the Gaslight, when you had all the folk purists with their roll-neck jumpers and thick glasses and little pointy beards, smoking pipes going ‘yeah, this is folk music’. Then they complained that people came in, used old folk modal tunings and old folk songs and sang their own lyrics over it. Which side of the fence do you want to be on?

It’s the same with psychogeography. People saying about certain works ‘that’s not psychogeography, sorry, we have to keep some purity to it.’ I guess people get used to what something is and want to own it, to protect it in some way, and I understand that. I understand why great naturalists want to make sure that the kind of rigorous approach to nature is maintained and not lost, to not become a sideshow. But I think that any art form has to progress and adapt if it wants to stay alive. Everybody benefits from that.

GB: What do you think as ‘edgeland writing’ itself as a genre? I’m thinking of the famous Paul Farley & Michael Symmons Roberts book, for example.

RC: Marion Shoard talked about it before them (they credit her in the book).

GB: And things like The Unofficial Countryside by Richard Mabey, going back to the 1970s. It seems to me that edgelands are much more likely a space urban people will experience than any pristine wilderness, that doesn’t really exist in Britain anyway.

GB: And things like The Unofficial Countryside by Richard Mabey, going back to the 1970s. It seems to me that edgelands are much more likely a space urban people will experience than any pristine wilderness, that doesn’t really exist in Britain anyway.

RC: For the first time in human history more people live in the urban environment than the rural one. 58% globally. Something like 85% in Britain. So of course, for most people, the closest green and different space outside of that urban consciousness – that Bataille called ‘the work consciousness’ – is this close liminal space, this narrow penumbra around our lives. Which we see, we see it out of our windows, we see it over the back fence, we see the buddleia defying the railway, bursting everywhere along these corridors.

GB: And buddleia is from China originally.

RC: Buddleia is a classic story. It was originally brought over by very rich and serious gardeners who tried to make it take in the country, and protected it at first because they didn’t want other people to have it, as it’s so beautiful. As I say in the book, it looks like a can of paint exploding. Then it jumped the fence and it became, over time, a menace. It became uncontrollable and it was on the blacklist for railway companies. It was having to be ripped up and torn down, costing millions of pounds to British Rail.

Then they had to review that policy when it became clear that it was almost single-handedly supporting large colonies of pollinators [bees and butterflies], and then suddenly it was more benevolent again, this rich green vein running through cities that could sustain various species that had been ravaged by our attitude to wildflower meadows and pesticides.

GB: That leads me neatly onto the topic of native/non-native species, and the kind of criticism George Monbiot came under when he published Feral, being accused of a kind of eco-nationalism. The buddleia is an interesting example of a non-native species that has had clear benefits and disadvantages.

RC: It’s a matter of time and perspective in many ways. 12,000 years ago technically nothing was native. The ice sheets were retreating back and the first colonising spores and trees were appearing. Rabbits and pheasants are non-native. It’s a difficult one to call. Of course I understand the impulse to want to keep landscapes as they are, that’s a natural urge, but at what time to stop the clock? What epoch do you reverse to?

I love the idea of rewilding and of there being more wild space. In edgelands, because no one gives a shit about them, you find nature getting on with things, with native and non-native mixing. I think the less interference we have the better – but what point are we regressing the land to? England 500 years ago? 200? For example 200 years ago we had vast tracts of farmed fields so that we had more hares. 500 years ago we didn’t have that many hares. Does that mean we should protect hares or not?

My take on it is that before you start you have to make people care about landscape. The first step has to be getting people to start thinking about themselves again as an inseparable part of the landscape.

GB: Is an important part of that finding places close to home?

RC: I think it’s crucial that people engage with their local spaces. Ultimately there has to be that local connection. Having somewhere close by means you can visit repeatedly, observe the changing of the seasons, to allow the merging of person and place that can only occur over time. If you go a woodland on the edge of town and you see foxes, you see rabbits, you start to know what they move, sound, smell like – it gives you a far greater sense of responsibility, empathy and understanding than a kind of cold classroom ethical stance that says ‘don’t eat cod as they’re running out in the Atlantic’. How that can mean anything to you if you’ve never caught a cod? You have to have a physical connection to a place, and the things that live in that place, to care about a place.

The disconnection we feel, the sort of hollowness, can be countered by taking a walk into a place where you can watch buddleia defiantly bursting full of life, full of nature, nature that doesn’t give a shit about the human world. It is itself, a perfect and pure pragmatic thing. That’s crucial to our health, and to our own understanding of ourselves.

GB: What is the role then of writing engaging people with landscape? One of the criticisms levelled at New Nature Writing is that the average metropolitan British person might use these kind of books as a form of escapism, never actually doing the things that you’re talking about.

RC: Number one: what’s wrong with that?

If you insist writing has to have a role in that, it makes it difficult for writing to have a sense of freedom. Enquiry, fascination, intrigue and trying to make sense of who we are and how we fit into the world – that’s what Common Ground is about. It’s not intended to make all who read it become an issuist.

I talk about the fact that the space in the book, that I love and know better than any other, is at some point going to be built over. That’s something you have to come to terms with. Places change, we all change. Change is something that we have to physically and mentally get our heads round and process.

Hopefully, if you read Common Ground you can’t fail to be intrigued about what lies around you. There’s no piece of British soil that isn’t freighted with stories. The layers and lives that run deep through this landscape, and of course the stories of the creatures that exist in these spaces, and the flowers and everything else. It’s triggering that is the point. It’s about awareness and it’s about looking, in a local sense and in wider biosphere-sense too. That’s always been my area of interest. We’re beginning to live in a world that is all-knowing but without any true knowledge. Our knowledge is broadest than it’s ever been, but also incredibly shallow.

There’s a quote I use at the beginning of the book, from the poet Patrick Kavanagh:

To know fully even one field or one land is a lifetime’s experience…a gap in a hedge, a smooth rock surfacing a narrow lane, a view of a woody meadow, the stream at the junction of four small fields – these are as much as a man can fully experience.

GB: And by the time you’ve ‘finished’ knowing a place, it will have changed, and you the observer will have changed too.

RC: That’s very true. I remember reading back through the field notes I had written and thinking ‘I’m not the same person anymore’. Now I’m a father I feel differently about things.

What drawing more closely to nature has always done is show us what we are and what we’re not. That’s crucial for us and it’s a perspective we’ve lost as a species, over the last 200 years particularly. This disconnection has led to a kind of blindness about how we treat each other and how we treat the earth. It’s destructive and terrifying. How can it be that there are [in the USA] Republican party candidates on a stage, all of whom don’t believe in climate change? It’s astounding. We’ve completely alienated ourselves from any sense of responsibility – all that stuff is mediated by so many layers. You go into Sainsbury’s a buy a bag of spinach, you don’t know if that’s the last bag of spinach in the world. You switch on a light, and you don’t know what that means, in a local sense or a wider sense.

What the human being is very good at is denying, and lying to ourselves. It’s a frightening thing. The way to counteract this is, again, to reconnect people to land and let them value it, let them see how it all works. Then people will have a toolbox with which to rail against this blind stupidity, this blind political madness.

GB: There’s a wilful ignorance about a lot of environmental issues I think.

RC: It’s a wilful ignorance that reinforces the line between human and nature, and that’s the line that’s always done the biggest damage. No matter how clever we think we are, we’re still beholden to the rhythm of night and day, of the seasons, of growth and death.

To pull all of this into a theory – I went looking for that common ground to sort of write myself, to draw new maps. All the maps with which I had navigated my life for ten years were correlating to London, 220 miles away. And I wound up alone, in winter, in a strange town I’d never lived in in a strange house with all my belongings boxed up in a hallway. The edgeland at first felt like somewhere I could align with because it was also caught between states – caught in this suspension between the present and the past. By drawing closer to it, listening to its histories and exploring the area, letting it manifest, I learned about those key things. I drew my new maps.

GB: Do you think these edgeland spaces appeal to people (writers especially) in the sense that thy can be a new place of transformation? Traditionally in folklore and fiction, the forest was the place where things happen and characters change – in a space that is somehow removed and out of time, neither past nor present. Is the edgeland replacing this in some way?

RC: Absolutely. They are a literal meshing of human and nature, so they act as a perfect microcosm for the world at large. In the past, woodland was a wild space. Very few people owned a wood. It could be dangerous, it was somewhere outside the normal experiences of many people.

GB: Also a space for people beyond society or the law – Robin Hood, General Ludd etc.

RC: Yes and edgelands are the same. They are the one space that isn’t privatised. The urban is completely privatised. The rural environment that we are told about, the farmland, is equally privatised. They are privatised spaces, but the edgelands are not because no one cares about them. It’s a space you can tramp around in with a sense of freedom, and be pretty sure that they’ll be no one else there. Or maybe just other writers with notebooks and pens . . .

I think it’s a space where people can genuinely feel a sense of wildness and freedom. It’s unowned, it’s dispossessed. It has the freedom of nature following its own rules.

To order Rob Cowen’s Common Ground, click here or you can find it on Amazon.

Gary Budden is co-founder of independent publisher Influx Press and assistant fiction editor at Ambit magazine. He lives in London. Click here to read his blog: New Lexicons.

[…] You might also like his article Common Ground: Rob Cowen on Edgeland Literature, Psychogeography & Nature Writing […]