This is a transcript of my talk at the Walking Inside Out Symposium, an event in Sheffield to launch the new book Walking Inside Out: Contemporary British Psychogeography, edited by Tina Richardson.

I’m an author of stories, essays and spoken word predominantly about place, and the experience of walking through places. I’m also the founder of Unofficial Britain.com, a website that takes a skewed look at the UK landscape.

The story of why I’m standing at a psychogeographical symposium begins on Hackney Marsh, East London in 2008.

I’d recently got married and moved into a flat in Clapton. My wife was pregnant. My party days were over. I had crippling backache from too much sitting at a computer, and thought a dog would get me out and about.

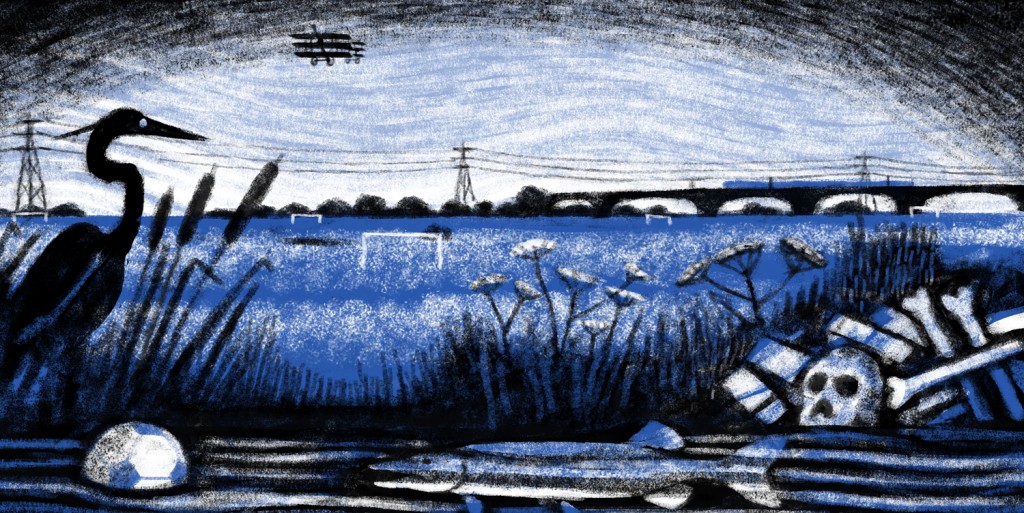

I bought a cocker spaniel and started to take him for walks over the canal at the bottom of the park. There I entered an extraordinary world. I don’t know if you’ve been to the Lea Marshes but at 11 am on murky days they are like a dreamscape… long horned cows, kestrels, pylons, railways lines, canals, empty football pitches, abandoned Victorian filter beds, all in the heart of the city, framed by London’s skyscrapers.

I walked there every day with the dog, through different seasons and aspects of light, finding strange objects like safes, duvet covers, clocks and dead swans, meeting mysterious characters coming out of the undergrowth.

I walked there every day with the dog, through different seasons and aspects of light, finding strange objects like safes, duvet covers, clocks and dead swans, meeting mysterious characters coming out of the undergrowth.

After two years I felt I had to get it all down, so I created a blog called The Marshman Chronicles. It was a nod to Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles. Similarly to the astronauts in his short stories, I felt like I was visiting on another planet that was strangely familiar, or that I’d returned from space to find my earth warped and out of kilter.

The Marshman Chronicles was an alternative map where I mythologised the underpasses, narrowboats, railway bridges, doggers and nocturnal drinkers. I included all my moments of paranoia, confusion and excitement. I didn’t place any limitations on the project or stick to realism. Simply describing the shape, colour and function of things didn’t really get across how the place felt.

I became fascinated by the space between place and imagination: that half-formed, subjective world. The daydream. The tangential thought. The mistaken impression. The irrational emotion. It’s a state of being which straddles perceived reality and the subconscious. I guess you could call it surrealism.

The first published piece I wrote about my experiences was A Dream Life of Hackney Marshes, an autobiographical story about a man who has a breakdown after his daughter’s birth, becomes addicted to cataract eye drops and begins an affair with an electricity pylon on the marshes. [Acquired for Development By…. (Influx Press, 2012)]

The idea was that while many people might see a row of pylons as indistinguishable, in a certain state of mind someone could see meaning in a single pylon. It’s an approach which puts power in the eyes of the beholder. It frees the mind of the person travelling through a landscape from the dictates of planners, architects, commerce and politicians.

The idea was that while many people might see a row of pylons as indistinguishable, in a certain state of mind someone could see meaning in a single pylon. It’s an approach which puts power in the eyes of the beholder. It frees the mind of the person travelling through a landscape from the dictates of planners, architects, commerce and politicians.

This became particularly important when the marshes were turned into a battleground before the London Olympics, with vested interests trying take control of the marshes should be… building car parks and paths through the fields, erecting a basketball centre on a wildflower meadow.

I’m not a particularly political person, but the act of wandering and freely imagining became a political act in the years 2010-2012, whether I liked it or not.

At the same time, I was active on Twitter where I discovered that what I was doing was known as Psychogeography, something I was only faintly aware of as the title of Will Self’s column. That’s when I was introduced to the likes of Laura Oldfield Ford, Iain Sinclair, Stewart Home, the Fife Psychogeographical Collective, Nick Papadimitriou, Mythogeography and Counter Tourism. A few months later I was invited by Tina Richardson to speak to the Leeds Psychogeography Group.

In 2013 Influx Press published my book Marshland ,which took it even further. It’s a surreal memoir that blends accounts of my walks with local myths, legends and uncertain historical events, linked by a thread of supernatural fiction.

In 2013 Influx Press published my book Marshland ,which took it even further. It’s a surreal memoir that blends accounts of my walks with local myths, legends and uncertain historical events, linked by a thread of supernatural fiction.

In the book I posit the marshes as a time-travel device, in which multiple experiences of the landscape, past present and future, real and imagined, could happen at the same time. Because for me, the experience of a place isn’t a map or a linear history. It’s a chaotic combination of what you see, what you imagine you see, what emotions you feel, the noise around you, the rumours you hear about the place, memories (your own and other people’s) and how you later talk about that place to someone else, transfusing your own myths.

This is why I write stories that blend fiction and non-fiction. Not as a gimmick, but as a necessity of expressing place. [To read my Quietus essay on this, click here]

Which brings me to ‘Wooden Stones’, my chapter in Walking Inside Out. I moved to Hastings in 2013 and continued the walking I’d been doing on the marshes, but in an entirely new landscape. I was assailed by sensations and memories from the last time I had lived by the sea, during a postgraduate year in St Andrews in 1996, a year that ended with the tragic death of my best friend.

The chapter is a conflation of walks in those first few months. It’s about how the smell, sounds and atmosphere of the seaside in Hastings transported me back in time and 900 miles north to the seaside in St Andrews.

It’s also about the phenomenon of written text in a landscape. I compare spontaneous rock graffiti carvings on the cliffs with the more formal memorial benches. Both encourage you to read, using your own interpretation and forming your own meaning.

To me, this is synonymous with psychogeography, which is both a form of reading the landscape, and a form of writing the landscape too, where you leave your own stories in the mud behind you.

This short extract from my chapter captures all those elements:

—————————————-

On a crankily humid day I slip through an alley beside the Dolphin pub and climb the steep steps alongside the Victorian railway lift that takes tourists to the top of East Hill.

On a crankily humid day I slip through an alley beside the Dolphin pub and climb the steep steps alongside the Victorian railway lift that takes tourists to the top of East Hill.

There are memorial benches towards the summit. The epitaphs are different in tone to those on West Hill, looser and wittier, with hints at an authorial voice – or even the voice of the deceased themselves, humming in the depths of their wooden chambers.

Jim & Trixie Butchers: A Wonderful Hastings couple

OLLY ‘9 TOES’ CAREY

Michele Campling: I don’t know where I’m going from here but I promise it won’t be boring

Never a Dull Moment – In Loving Memory of Gary Batcheler

At the very top, by the exit of the funicular lift there is a single bench beneath a tourist information board that reads:

Mad John?

1945-2009

Who on earth were you, Mad John?

I sit down by his name. His bench is positioned so that it takes in the whole Hastings vista – the Stade, the promenade, the pier, and the curvaceous rump of West Hill rising from the old town. Unlike the infrastructural location of many benches on that rival elevation, this seems the most natural spot someone would stand to soak it all in. I can imagine John’s gaze as if it were my own. I smirk on his behalf at the stuffy formality of those memorial benches on West Hill, some of whom he knew when they were more than just names on wood.

There’s Mrs Jenson who was “much beloved” – oh yes, beloved alright, she was known as the town bike back in the ‘50s. Everyone had a go. Then there’s Dicky Pierce. Christ only knows why he’s up on that hill. The lazy fat sod barely left his bar stool at The Stag. Harry and Jill Michaels, “a loving couple” – God, you should have heard Harry going on about her behind her back until that day she whopped him with a saucepan. Yet there they all are, laughs Mad John, dead and turned to benches instead of dust, arranged in rows, seething at each other for taking the superior spots.

There’s Mrs Jenson who was “much beloved” – oh yes, beloved alright, she was known as the town bike back in the ‘50s. Everyone had a go. Then there’s Dicky Pierce. Christ only knows why he’s up on that hill. The lazy fat sod barely left his bar stool at The Stag. Harry and Jill Michaels, “a loving couple” – God, you should have heard Harry going on about her behind her back until that day she whopped him with a saucepan. Yet there they all are, laughs Mad John, dead and turned to benches instead of dust, arranged in rows, seething at each other for taking the superior spots.

Oh, how they’d love to wrench their little wooden legs from the earth, grow big eyestalks, and go clattering across the hill like crabs to find a viewpoint away from those tourists and their big sweaty arses! Ah, for shame, you dead of West Hill! It’s here on East Hill where the benches are wild and random, with the most majestic vistas! East Hill is where the chaos happens!

From John’s bench I can see a weather system approach, an opaque twister moving over Bexhill-on-Sea. Rain falls on distant boats. Sensing a squall, restless gulls spiral up from the cliff side like cinders rising from a fire.

I envy them sometimes. Birds are the expression of the wind. They travel invisible paths in the sky, gone as soon as they are created, never to be repeated. These animals are free to live in the moment. But we humans are entrenched in the earth. The routes we travel are scars on the topography. Memory trails where can’t help but leave our footprints, nor avoid following the footprints of others.

Walking is unavoidably an act of writing and reading. Even without memorial benches, the landscape is heavy with text.

————————————————-

You can order Walking Inside Out from the publisher here or on Amazon here.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gareth E. Rees is author of Marshland: Dreams & Nightmares on the Edge of London. His work appears in Mount London: Ascents In the Vertical City, Acquired for Development By: A Hackney Anthology, and the spoken word/classical music album A Dream Life of Hackney Marshes.