WORDS & PICTURES by GARY BUDDEN

It’s a compelling thought.; the monster Grendel inhabiting the bleak marshlands of the Isle of Harty (part of what we now call Sheppey), just over the water from the town of Faversham, separated from the mainland by The Swale.

These islands tend to overfeed the imagination; lost tribes can dwell there, grisly remains, evolutionary dead ends, the sons of Cain.

Sheppey, and the other small islands that appear as odd unmarked blanks of green on Google Maps, hold dark histories. Deadmans Island and Burnt Wick Island, so close to home and practically unknown, are borderline inaccessible. They hold the mass graves of Napoleonic French prisoners who died on the prison hulks (you’ll know them from Great Expectations) and their bones now rise from the silt.

Walk the Hollow Shore between Faversham and Whitstable, look out over to the island across the Swale, no one else around and the wind stinging the eyes. It’s easy to feel Anglo-Saxon in such a place.

More than anything we want the monsters to be there.

*

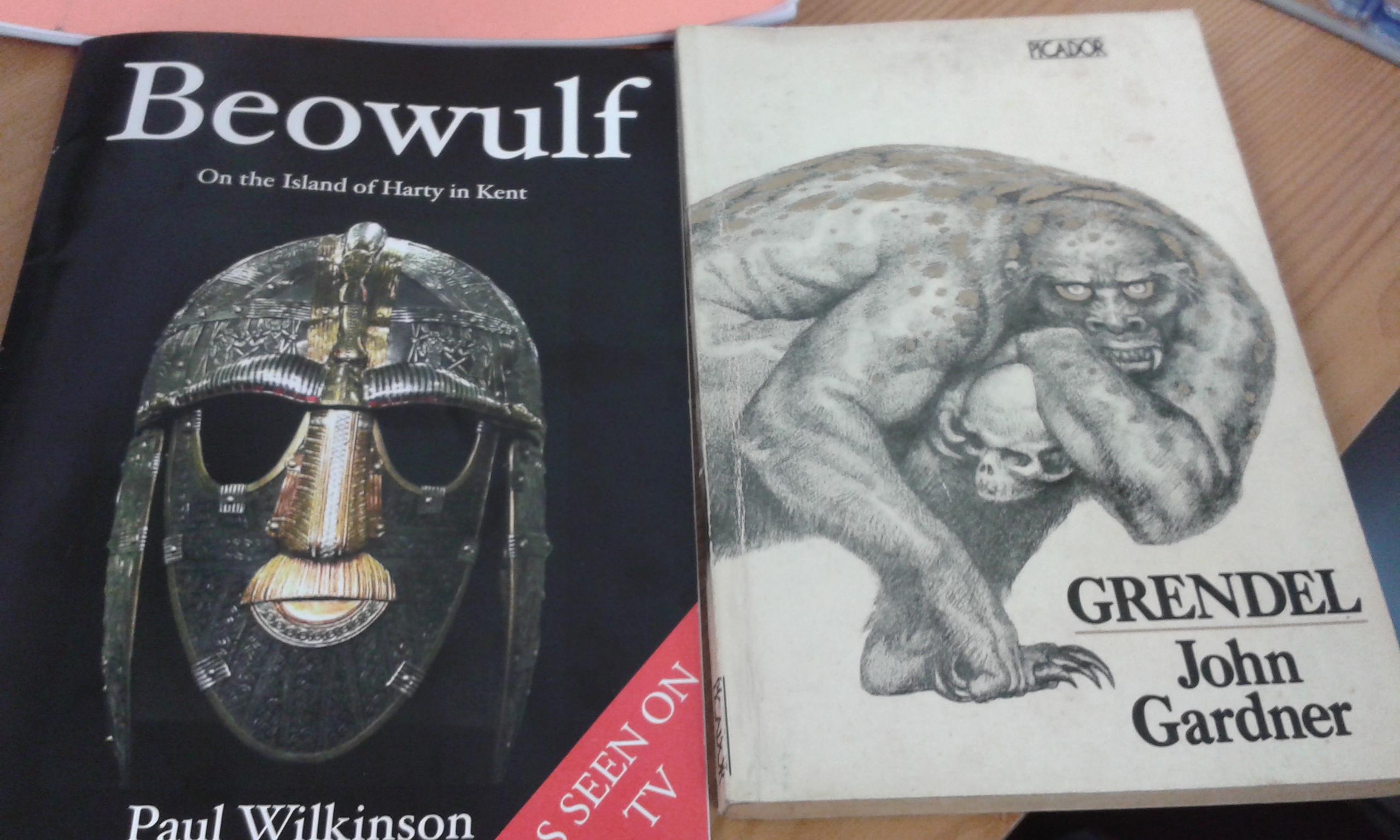

I remember looking at the Beowulf manuscript in the British Library for a long time the first time I saw it. It exerted a pull over me that beat any Chinese scroll or Lewis Carroll diary. I read the Heaney translation, discovered American writer John Gardner’s monster-perspective novel, Grendel, as part of the Fantasy Masterworks series (terrible cover). I even watched the film written by Neil Gaiman and with Ray Winstone as our founding English hero, getting entangled with a version of Grendel’s mother who was rather sexier than I’d always imagined.

When I started researching the areas of north east Kent where I grew up, especially the stretch of coast along the Thames estuary, I came across a curious (and spurious) piece of information on the Faversham website:

Nearly ten years ago Dr Paul Wilkinson, a Swale archaeologist, and Faversham journalist and business woman Griselda Mussett contributed a Faversham Paper which makes a strong, and believable, claim based on topographical and oral and written folk history that the Beowulf legend had its origins among place names that were commonplace and are still to be seen around the Faversham area.[1]

I tracked down the papers via the Faversham society and duly received them in the post. I felt like I was falling down a rabbit hole of crackpot theories and dubious speculation.

Was I going to become one of those people?

If I’m honest, I wasn’t much interested in the truth of any of the theories. The story appealed. Ray Winstone’s cockney accent suddenly made a sort-of sense. Beowulf as the ex-Londoner moved out to the estuary.

Paul Wilkinson’s colour booklet, Beowulf On the Island of Harty in Kent proudly proclaims AS SEEN ON TV in its bottom right corner, and features the Sutton Hoo mask as its cover, which already seems to be muddying the issue. Near the beginning, he does concede what we’re really dealing with here is mythology, not archaeology or science:

Mythology, on the other hand, is concerned above all with what happened in the beginning. It’s signature is ‘Once upon a time’ and our English beginning could be a small island called Harty just off, but belonging to, the port of Faversham in Kent.

It could be, but it’s most likely not. Let’s dispense with the facts and go straight to the story. In this tidal landscape, where land is eaten away and the sea silts up to become shore, where diseased bones rise from the mud, where the very definition of what is land and what is not is unclear, slippery facts, half-truths and downright lies seem appropriate.

In this Kentish interpretation of the tale, Harty becomes Heorot (Hrothgar’s hall). Heorot sits at the heart of a large Lathe, or administrative area, the schrawynghop, an area ‘inhabited by one or several supernatural malignant beings’. (Insert Sheppey joke here).

Hop means a piece of enclosed land in the middle of marshes, or wasteland. Wilkinson cites sources who claim that the only linguistic clues we can glean from the Old English is from the text of Beowulf itself, where the monsters’ lairs are called fenhopu and morhopu – marsh retreats. ‘Schraw’ approximates to many words from old Germanic dialects meaning dwarf, goblin, devil, the villain, and so on. Here lies the problem of language; its imperfect nature, its multitude of meanings and interpretations, allowing us, literally, to read what we want into it.

The theory even goes as to suggest that Beowulf was buried under Nagden mound (a possible artificial hill that was destroyed in 1953 by men contracted to rebuild the sea wall between Faversham and Seasalter, after the great North Sea flood.), though by this point the theory has fallen more into wishful thinking and a lot of ‘maybes’ rather than anything that could approximate a credible argument.

*

In my fictional landscape, Grendel and his mother fit in well with the bodies of those dead Frenchman, the prisons across the water on Sheppey, the bleak marshes, the boxing hares and the black curlews of my own fictions.

In my fictional landscape, Grendel and his mother fit in well with the bodies of those dead Frenchman, the prisons across the water on Sheppey, the bleak marshes, the boxing hares and the black curlews of my own fictions.

I know these tidal flats and malignant bogs were dry land once, attached to the Doggerland landmass that connected what was to become Britain to the coasts of Germany and Denmark. My mind already is flowing with ideas, stories of the last remaining malignant supernatural beings that inhabited Doggerland making a last stand in the Kentish marshes.

Wiped out by Ray Winstone. Grendel having his arm pulled from its socket on the demon marsh in the Thames estuary. A dragon above Faversham.

It’s a good idea for a story, right?

Maybe that’s enough.

For more information on the Beowulf in Kent theory, click here

And here’s a whole website dedicated to refuting the theory here

NOTE: I haven’t been able to find much about this being on TV. If anyone can find the video, please send it in.

[1] http://www.faversham.org/history/people/beowulf.aspx

Gary Budden is co-founder of independent publisher Influx Press and assistant fiction editor at Ambit magazine. He lives in London.

Hi to see the BBC programme go to news page at http://www.kafs.co.uk and enjoy! PS also see my PhD thesus published by BAR- subject-‘The Port of Faversham’