WORDS: Gareth E. Rees

The train stops at a level crossing in an East Sussex field. As the train pulls away I’m left on a tiny platform beside a sign which reads:

Winchelsea

Ancient Town, Cinque Port

Winchelsea town is ½ mile south east of the station

A country road winds south east through freshly cropped fields, criss-crossed with telegraph poles and littered with crows. There’s no sign of a town, only a leafy hill rising in the distance. This must be the ‘new’ Winchelsea, built out of harm’s way in 1288 at the orders of Edward I.

The original town lies beneath the sea, beyond Camber Sands. Its death began with a climate shift in 1233. Storms battered the coastline. Heavy rains and high tides brought floods. Then in 1250, there was a great storm, described by the chronicler Holinshed:

“On the first day of October the moon, upon her change, appearing exceeding red and swelled, began to show tokens of the great tempest of wind that followed, which was so huge and mightie, both by land and sea, that the like had not been lightlie knowne, and seldome, or rather never heard of by men then alive.”

During this storm the sea tide did not ebb, rather it surged through the town with biblical ferocity, destroying bridges, mills, houses and churches. The shingle bank on which Winchelsea was built began to break up. By 1258, the sea was surging further inland, sweeping away large parts of the town. And by 1287 the whole place was under water.

For a few years, the displaced townsfolk could see ruins of their home at low tide.

Then it vanished forever, a Sussex Atlantis.

The land on which I walk became a busy tidal estuary, boats sailing in from the Channel towards the turreted gates and walls of New Winchelsea, built on a hill for safekeeping.

Remnants of the medieval landscape survive in the names of the properties I pass: Ferry farmhouse and Ferry Cottage. At the foot of the hill, the road rises steeply towards a mediaeval gateway. Next to it is a house called ‘One Moneysellers’, harking back to the time when Winchelsea was a major Channel port and foreign money could be changed here upon entry.

Remnants of the medieval landscape survive in the names of the properties I pass: Ferry farmhouse and Ferry Cottage. At the foot of the hill, the road rises steeply towards a mediaeval gateway. Next to it is a house called ‘One Moneysellers’, harking back to the time when Winchelsea was a major Channel port and foreign money could be changed here upon entry.

It’s hard to believe, looking out from a silent street across the flat green valley. In the centuries after new Winchelsea was founded, the upper reaches of the estuary were damned and reclaimed as farmland. The harbour began to silt up. By the 16th Century, the town’s role as a port was over.

On its southern flank is what remains of the Strand Gate. In 1350, royalty stood on the walls here to watch the Battle of Winchelsea, when English ships clashed against the Spanish fleet at Dungeness.

On its southern flank is what remains of the Strand Gate. In 1350, royalty stood on the walls here to watch the Battle of Winchelsea, when English ships clashed against the Spanish fleet at Dungeness.

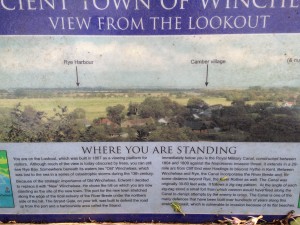

The walls are gone. Now there’s only The Lookout, a Victorian shelter built for tourists to view the panorama: Rye harbour, Camber village, the Royal Military Canal, and Spadlond Marsh.

In the middle of the Rye Harbour nature reserve is Camber Castle, a compound built by Henry VIII on a spit of land poking out into the sea. But silt and shingle have left it lonely and awkward in the marshland.

Beyond the castle you can see the latest spit – a corridor of pylons and wind turbines leading to Dungeness.

It was shingle which once bore, and then destroyed, the port of Old Winchelsea. It is shingle which now bears a nuclear power station. On temporary shelves we build things of permanence. Such is our folly!

In March 2014, energy company EDF admitted that it had shut down its nuclear reactors for five months because of flood fears, borne of rising sea levels. An internal report revealed that shingle bank sea defences were not “as robust as previously thought”.

It took thirty years to sink Old Winchelsea. Its bones lie beneath the sea bed, benign and forgotten. But should it become a second Atlantis on the south coast, the bones of Dungeness will glow for an eternity.

Gareth E. Rees is author of Marshland: Dreams & Nightmares on the Edge of London. His work appears in Mount London: Ascents In the Vertical City, Acquired for Development By: A Hackney Anthology, and the album A Dream Life of Hackney Marshes.

I am from Camber Sands and Rye and am writing a booklet on the Jews of Jury’s Gap who were murdered by men from New Winchelsea. Until I read your remarks about Dungeness power station, I was slightly doubtful if Old Winchelsea had been built on shingle. I thought perhaps there might have been a more substantial outcrop as at Rye around which shingle gathered. Now I share your belief that greed and opportunism can override common sense.

Thanks for your comment – let me know when you’ve published your booklet. Sounds intriguing.

I should add that the murder of the Jews took place in or around 1290 AD.

Looking at the older records, it appears that the original settlement was on a low lying island with a forest that stretched in sections westwards past Hastings. The forest was also swept away but its prehistoric foundations are visible at Pett Level.

My booklet The 1290 AD Massacre of the Jews at Jury’s Gap Romney Marsh is available for free from academia.edu or from me at sheba.edu@gmail.com