LOCATION: Wiltshire

WORDS: Gareth E. Rees

It’s a long road to Little Imber, Salisbury plain’s ghost village. The MOD have opened it for public access, as they do occasionally at Easter and Christmas.

Turning off the A360 from Tilshead, the checkpoint is empty, barriers removed. A tank is hunkered on the horizon. DANGER NO PUBLIC ACCESS signs warn me not to deviate from the mud track in case my car is shredded by UNEXPLODED MILITARY DEBRIS.

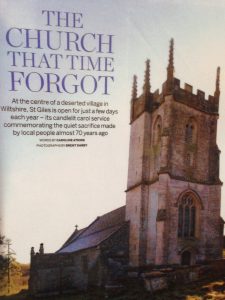

After a twisting drive through a worn, pitted landscape I see a church spire poke above the trees nestled within a shallow valley. Minutes later I enter the village through a road oozing blood red mud and park beside a corrugated-roofed house, riddled with bullet holes near the American Road, surely a name that came after the village was sequestered for the war effort in 1943, the residents told to leave for the good of the nation.

You’ll get it back after the war, they were told, we’re only borrowing it, so they said, though nothing was written down. Nothing official. The MOD made sure of that.

Imber had long been an inconvenience for the military, sat isolated in the middle of a vast training zone on Salisbury Plain. It was the last residential stronghold amidst their never-ending war games, surrounded by firing ranges. The little village had been increasingly encroached upon since the army first laid claim to the plain in 1897 and began shelling the shit out of barrows and standing stones, filling the skyline with smoke and shaking crows from the trees.

Most of what I pass at first appears to be the original village, its buildings scorched by fire, breeze blocks patching up sections of the brickwork blown away by mortar shells, roofs replaced by corrugate iron. Each house is daubed with a large painted number. They’re like branded cattle ready for slaughter, or prisoners in a chain gang.

I peer inside at blasted spaces, devoid of fabric or furniture, with gaping fireplace cavities and concrete staircases to nowhere.

As the road twists towards the church, the scene changes. An estate built in the 1960s is a simulacrum of Belfast, rows of residential houses ready to host close-hand combat action. These are houses in which nobody ever lived, designed to look like other houses in another place in which people would die. They stare out like haunted faces.

On the other side of the road is Imber Court, once an ivy-covered mansion at the centre of local life, now shorn of its roof, windows sealed with green metal panels, gates chained.

A little further down is what remains of The Bell Inn, built in 1769. I sneak onto a forbidden track behind the rear wall of the old manor house to find the remnants of Imber Farm, the surrounding grasses trampled down by heavy vehicles. In the 18th Century there were kennels behind the Manor house for the coursing hounds. In the early 20th Century villagers would tell the local children that sometimes they could hear the chains of ghost dogs rattle at night. Or perhaps this was an auditory premonition of the tank chains and spent bullet casings to come. The ghost of a dead future.

There is no more village further west from here, only gouged verges where tanks have ploughed their course and a fenced area harbouring gravestones from what was once the site of the thriving Baptist church.

I turn back towards St Giles’ church, back through the fake Belfast and up an incline, passing a sign in glorious memory to the men of the village who served in the Great War. The village was close knit, numbering only a few hundred people. You can see it from the clustered surnames of those who served: four Carters, seven Daniels, two Greys, two Potters, two Tinnams. One Kitley died, the other Kitley wounded.

Near to this is another memorial, this time dedicated to the entire village for sacrificing itself for the war effort, although this sacrifice was far from voluntary and nobody realised at the time that it was the end for them and their history.

The parish itself was abolished in 1991 after the military refused to give it back and all the fight went out of protesters who made continued attempts to secure a return in the decades that followed peace with Germany, to no avail. But it’s an academic matter now. There is very little left to which anyone could return.

The church is technically the only piece of the village that remains outside MOD jurisdiction. It is surrounded by high barb wire fencing, festooned with OUT OF BOUNDS signs. Even after the villagers were forced to leave, they were permitted to bury their dead among the smashed gravestones. I see stones from 1954, 1976, 2003. Their burials must have been strange affairs beside the empty church, within the high fencing, beneath the shattered tower, where no hymns were sang and few birds alighted.

The church has now been restored. It’s an open day for the public. Inside the building are trestle tables manned by those who loved Imber, former residents and descendants with pamphlets and books, photos of the village in the years before its destruction, press cuttings and laminated copies of Sunday supplement magazine coverage with titles like ‘The Village That Time Forgot’.

There’s cheap tea and warm conversation. People with muddy boots. Dogs on leashes. Bored children.

I buy a copy of Little Imber On the Down, a local history by Rex Sawyer who is too unwell to come and sign books like he used to, a friendly woman explains to me.

There aren’t many other histories of the place. Time itself was commandeered by the military. All that Imber has now to maintain its memory is a clutch of defenders, keeping the place in mind, not letting it slip away, for the sake of the souls beneath the gravestones and the broken dreams of their ancestors.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gareth E. Rees is author of Unofficial Britain (Elliott & Thompson, 2020) Car Park Life (Influx Press 2019), The Stone Tide (Influx Press, 2018) and Marshland (Influx Press, 2013).

Great piece Gareth.

Thanks Tristan. It was a strange way to spend the penultimate day of 2016, but also somehow appropriate.

Cheers!

Gareth

great read. as usual. thx

Excellent – really enjoyed this. It’s amazing how much of the countryside has been taken over the military.

Thanks Alex. I was eager to check it out, having recently read The Village that Died for England, which is about Tyneham. http://www.patrickwright.net/books/the-village/about/

Cheers

Gareth