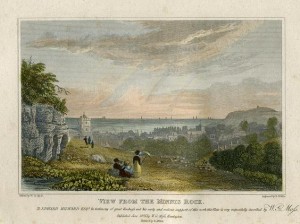

LOCATION: Hastings, East Sussex

WORDS: Gareth E. Rees

East Hill, a promontory of the South Downs: rolling green contours on a plateaux of sandstone high above Hastings.

A funicular railway lift rattles up its seaward face. To its east, cliffs range towards Fairlight. Cradled in its westerly lee is the old town: a quaint jumble of slate roofs, Tudor beams and medieval churches. At its crest, overlooking the town, are three black arches – a fake church carved into the rock by a man named John Coussens in the 18th Century.

The arches have obsessed me ever since I first noticed them. It wrote a post about them here. They vanish behind gorse and brambles in the Summer, but in the winter it’s easy to see their precisely proportioned lancet-shaped forms.

My favourite way to approach them is to walk from All Saints Church, onto Harold Road, then up a footpath to High Wickham: an elevated row of Victorian houses embedded in the flank of East Hill, almost every one bearing a blue plaque commemorating a writer or artist who lived there.

I took this walk regularly for almost a year. Each time I obliviously passed by an even greater mystery. For beneath the footpath, metres away from my route, hidden off the road in dense foliage behind a bus stop, is the Minnis Rock.

Hoax or Sacred Site?

Like the Black Arches, there are three entrances. But they lead into a physical space: three equal sized chambers, with a hole in the partition walls so you can move between them. A few hundred years ago, this would have been located on a route into town, with clear views south towards the church, houses and the sea.

The first historical documentation of this feature is in a 1663 drawing by a Dutch artist, where they are used as a sheep shelter. The rock is said to be named Minnis because the rough slope leading up the side of East Hill was common land for grazing of sheep, known as ‘menesse’ land in Old English. However in 1892 an antiquarian called Byng Gattie claimed that it was derived “from the Celtish (or welsh) word Menys, signifying a steep ascent.”

To confuse things further, in the 18th Century, when Coussens was busy carving his Black Arches – perhaps out of sheer boredom – this slope was known as Mount Idle.

I learned of the Minnis Rock’s existence after my Unofficial Britain post on Coussens, when I was contacted by Rt. Hon. de Mont Saint’e Michel de l’Aigle [Earl de Mychel Wayne Quinnell], husband of Shani Quinnell (nee Coussens of Hastings, a direct descendant of John & Henry Coussens).

He wrote: “John Coussens created the hoaxes, the Black Arches and the Minnis Rock… there has never been any written information on this character. It has been passed down from one generation to the other.”

Could Coussens have created both these landscape features?

The Dutch sketch from 1663 challenges that notion. But could Coussens have been attempting to reproduce the Minnis Rock? And if so, why? What did he know, or suspect, about the Minnis rock?

There is a book from 1920 called Hastings of Bygone Days – And the Present by one Henry Cousins, who may be a relation of Coussens. He writes:

“The Minnis rock, with three openings, has existed for centuries… it is supposed by some to be an instance of a rock hermitage and the only one, except at Buxteds [nr. Uckfield], in this country.”

However Cousins doesn’t link its provenance to the Black Arches the existence of which he considers a total mystery. All he can say is: “It was once a favourite rendezvous for smugglers, who frequented the spot to partake of brandy and milk, and to spin yarns of their encounters with the blockade men.”

In his 1892 article for Sussex Archaeological Collections Relating to the History and Antiquities of the County, Byng Gattie writes that the Minnis Rock is “without doubt…. an ancient oratory or chapel hundreds of years old, situated near the sea for the express benefit of the sea faring population.”

He explains: “We may suppose that the centre cave might have been the oratory, the right (or south) a sort of vestry, and the left (or north) a temporary lodging for the priest.”

Gattie continues his religious interpretation for the Black Arches, concluding that the most likely theory is that the arches were began “ages ago – by one of our pious forefathers for the purpose of establishing there a seaside oratory, and that the designer probably died, or for some reason, was unable to finish the work; and as nobody undertook its completion the three arches were left much as we now see them, saving the effects of time and weather.”

He provides no evidence for this, only that he finds it incredible that “these carefully measured arches, cut in the face of the solid rock, were cut for no possible reason or purpose, either useful or ornamental.”

I’m not so sure about that. There are plenty of reasons a person might want to alter the landscape, be it for mischief, artistic endeavour, secret coding, a need for a legacy or that yearning for the picturesque which characterised the 18th Century. Could these two sacred sites be a form of sculptural graffiti?

A year after Gattie’s article was published, Mr Charles Dawson entered the fray…

“Hoax!” Cries Famous Hoaxer

At this time Dawson – a solicitor by trade – was a co-founder of the Hastings and St Leonards Museum Association, and a member of the Sussex Archaeological Society. In a 1893 newspaper article he claimed that a sorely mistaken Mr Gattie had discovered a “modern antique… carved in the latter end of the last century, by a Mr John Coussens, who was born in 1750 and died in 1836.”

Dawson added petulantly: “Anyone who has studied the history of Hastings could not imagine that the Oratory theory of Mr Gattie, as applied to these caverns, could be at all probable. Long before the period of pointed arches in England, the shores and the cliffs of Hastings bristled with the towers and churches and chapels, any of which could have been far more accessible and easily seen at sea than either the Black Arches or the Minnis Rock.”

At around the same time he was scribing these words, Charles Dawson embarked upon a series of his own hoaxes – mummified toads entombed in flint, doctored prehistoric mammal tooth, faked Roman cast-iron statues and even a sea serpent sighting in the Channel – that would culminate in the ‘discovery’ of the Piltdown Man: a missing evolutionary link that was, in fact, an orang-utan jaw and human cranium sneaked into a million-year old gravel pit.

Dawson was probably miffed that he hadn’t first had the idea to excavate the caves. With his special skill set, he undoubtedly would have ‘found’ something to make them archaeologically significant.

For more about the Black Arches, the Minnis Rock, Charlies Dawson and the occult landscape of Hastings, read my book The Stone Tide.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gareth E. Rees is author of Unofficial Britain (Elliott & Thompson, 2020) Car Park Life (Influx Press 2019), The Stone Tide (Influx Press, 2018) and Marshland (Influx Press, 2013).

The houses on High Wickham aren’t all Victorian. Many are older. I grew in one and it was Georgian. We played in the caves as children.

Hi Ellie – thanks! Did you share any stories/myths/legends about the caves as kids?

Hello

I have lived in Hastings all my life as have my dad and mum and there familys before them,

I thought I know most things about Hastings but I have never seen or heard about the black arches, I would like to see them , could you tell me where they are please.

Kind regards

Joe

Hi Joe – sorry for the delayed reply, if you look up onto the hill behind All-Saints Church they’re there on the brow of the hill – to access them, go onto East Hill and then simply cut down a path near a viewing bench when you can see the church below you and to the right a bit.